Composition Forum 27, Spring 2013

http://compositionforum.com/issue/27/

Latino/a Student (Efficacy) Expectations: Reacting and Adjusting to a Writing-about-Writing Curriculum Change at an Hispanic Serving Institution

Abstract: Using data from two surveys and end-of-semester reflections, researchers learned that students enrolled in writing-about-writing (WAW) courses are initially intimidated by the demands of a WAW curriculum, but the students’ perceived inability to complete the requirements contradicted survey data and final written reflections. Ongoing public conversations surrounding WAW curriculum and movement may lead faculty working with high at-risk populations, including but not limited to Latino/as, hesitant to adapt this approach, but the researchers challenge these perceptions and call for additional research to confirm that students who complete WAW courses have an increased sense of self-efficacy towards academic writing.

Advocating that (first-year) writing courses should “empower students to understand better how writing works in the world and in their lives” (Wardle 176), Doug Downs and Elizabeth Wardle’s 2007 article “Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions” named a pedagogical movement and sparked debate about what it means to teach writing in first-year courses. To dispel misconceptions about the teaching of writing, including the notion that a one-year course can prepare students to transfer writing abilities to other writing situations across the campus, Downs and Wardle argue that first-year courses should foreground “research in writing and related studies by asking students to read and discuss key research in the discipline and contribute to the scholarly conversations themselves” (Carter 3). The course profiles, articles, collected essays, and textbook authored by Downs and Wardle propose a structure that brings together scholars from various pockets across the country, who have contributed to the conversation about aligning the content of first-year writing courses with disciplinary knowledge (Beaufort; DeJoy; and Dew). It took an article in a flagship journal, however, to thrust the conversation into a more prominent light and reveal the complexities within this approach to first-year writing (FYW).

Though the article was not meant to start a movement,{1} the growing interest and support for the writing-about-writing (WAW) approach is undeniable, as Laurie McMillan recently noted in her review of the textbook released in January 2011. As a collective voice, the WAW movement keeps repeating one refrain: if our aim is to teach writing, then “[t]he likelihood of students gaining sufficient background in a content field while the course remains focused on writing is greatest when the course content is writing about writing” (Downs and Wardle, “What,” 175). This insistence that the content of and purpose for a writing course come from disciplinary conversations is not without problems, and Downs and Wardle openly acknowledge two key challenges in the WAW approach. First, the rigorous reading and research requirements mean “[u]nderengaged students may be at greater risk of failing the course than their more invested counterparts” (“Teaching” 574; emphasis added). Second, the pedagogical requirements stretch instructors, who “must be present to students who seek their guidance and perspective” and willing to “check their own conceptions of writing” (“What” 183; emphasis in original). Moreover, WAW demands teachers overcome their own perceptions about student abilities, adopting an attitude of “respect for and belief in students themselves—what they know and what they’re capable of achieving” (“What” 183). Downs extended this point recently, suggesting that WAW “honors some of the foundations of our field” by recognizing that students arrive in our courses as writers who have something to say and by “refusing to see from a perspective of student deficit and lack, instead insisting that the students who come here are already literate, already know ‘how to write,’ already have things to say” (“As If”; emphasis added).

Our study is about what happens when writing teachers ignore published perceptions about a student population as deficient. Whether you know it or not, you’ve likely already read about our students. The University of Texas-Pan American (UTPA) is an Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) on the southern border of Texas, and there have been very public conversations about what it means to teach writing with our student population and populations with similar make-ups: first-generation (largely minority) students are often characterized as “not quite ready” for college writing and reading assignments. Given the public discussion about the challenges of a WAW curriculum, it may seem odd that three years ago, a small cohort of writing instructors began using a writing-about-writing (WAW) curriculum in our First-Year Writing Program. Because we refused to see our students from a vantage that has been labeled a “rhetoric of lack,” we implemented a curriculum that asks students to read texts about information that should have been familiar (reading and writing) and expected them to think and act and write like novice scholars—two key features that make some think WAW may be too much for first-year students. As we listened to our students during the first two years of this program—students who are usually categorized as at risk and under prepared—we learned that they were finding their own means of re-creating their academic identities and improving their writing self-efficacy. We learned that students are capable of more than they imagined before taking our courses, offering a glimpse into the role that writing-about-writing (WAW) pedagogies might play in emerging conversations about the effect of student dispositions on writing instruction.

The demands a WAW curriculum places on instructors and students have been very real to us as a faculty member and graduate student at UTPA, one of 293 HSIs in the United States. As others have suggested, working at an HSI means working in an environment of ambiguous definitions (see Méndez Newman; Charlton and Charlton). Before a university or college can be designated as an HSI, at least 25 percent of the student population must be Hispanic, and approximately half of all Latino undergraduates were enrolled at HSIs in 2009-2010 AY. In fall 2010, UTPA enrolled 18,744 total students, 88.5 percent of whom were Hispanic. UTPA is eligible for Title V monies because 50 percent of students are low income. Ninety-three percent of our students come from the four counties in our regional area, which not only has a 12 percent unemployment rate, but 35 percent of the population lives in poverty with a per capita income for counties surrounding the university averaging under $8,800. It is no surprise, then, that 2,283 of the 2,399 first-time, full-time freshmen enrolling at the university in 2010 qualified for need-based financial aid under the federal methodology, so students received more than 85 million dollars in grants (Office).

These statistics coupled with a quick survey of literature related to teaching writing with Latino/a students reveal what we suggest are (mis)conceptions and false expectations about teaching writing at an HSI and learning about writing in an HSI. Some of these perceptions focus on (perceived) differences between teaching in “traditional” composition classrooms and “Latino/a” composition classrooms: under-prepared writers, lower graduation rates, overt family responsibilities (see Ramirez-Dhoore and Jones), and others suggest that for students and faculty to succeed at HSIs we all need “new understandings, new pedagogies, and specialized training” (Méndez Newman 17). As Jonikka Charlton, former Writing Program Administrator (WPA), has suggested, “it is common to hear faculty, administrators, and others describe our student population as under-prepared and at-risk” (Charlton 3). In her profile of the WAW approach in UTPA’s Basic Writing STUDIO courses, Charlton recounts what it was like introducing the WAW approach on our campus. In 2009, freshman at UTPA had an average ACT score of 19 (Office), so she “knew it would be a hard sell to get faculty to bring thirty-plus page articles written for scholarly journals into their classrooms, particularly with freshman. Particularly with our freshman” (3; emphasis in original).

Instructor anxiety or concern about UTPA students, unfortunately, is not a private matter; the above authors have all written about and worked at UTPA. These public discussions contribute to our anxiety over the public perceptions of our students and, by extension, students enrolled at HSIs and Latino/as across the country—a perception that Charlton and Charlton refer to as a “rhetoric of lack”:

While university administrators, local politicians, and happy transplants speak of the community’s untiring work-ethic and artisanship, we also hear students, teachers, administrators, and public documents giving voice to a rhetoric of student deficiency. . . . At best, we all know that our students, by their very presence on campus, represent a hope of transforming their community through their success at the university, but you don’t have to attend too many faculty meetings or read too many reports on Hispanic education before it’s clear that a dominant vision of Hispanic students sees them as at risk and under prepared. But the students we see every day don’t seem particularly “at risk” or “under prepared.” That vision of our student body is not one we recognize. We can’t say we know that student body. (68-9; emphasis added)

Nor can we. We do not believe that students enrolled at UTPA or other HSIs across the country are collectively, programmatically, or essentially under-engaged. Because we didn’t identify with the above perceptions of our students, neither of us were hard sells, but as instructors new to the WAW curriculum, we didn’t know what to expect.

We did, however, know what critics were saying about the key challenges presented by WAW courses. In their response to Downs and Wardle, Libby Miles et al. suggest that WAW courses risk “miring all students down in the specialized discourse of an advanced discipline” (504), ignoring and dismissing “the general education function of the first-year course” (507). Even Adele Richardson, a “banner carrier” for the approach, doesn’t deny “that sometimes incoming freshman, who are not being all they could be academically, flounder with it.” Two years into the WAW approach, we don’t like the words miring and floundering because they remind us too much of the other narratives circulating about who our students are and what they might accomplish. Yes, our students must work to meet our course requirements, but aren’t they supposed to? The running joke in our hallways is a t-shirt slogan: “College. It’s harder than high school.”

We do not dispute nor do we ignore the complicated off-site realities that students bring into our classrooms. We see and hear about the struggles with technology, financial resources, child and elder care, and work responsibilities. However, we do not believe that these off-campus, at-risk characteristics, our status as an HSI, or even students’ self-beliefs prior to enrolling in courses means UTPA students lack the ability or willingness to persevere in the face of the challenges they encounter in our WAW courses. In fact, our study suggests that the key challenges presented by the WAW curriculum may be essential in affecting change in their dispositions, namely their self-efficacy beliefs. By completing a WAW sequence, our students came to see themselves as “enabled, not disabled, writers” (Downs, As If). By seeing our students through this lens, we cannot ignore the one-sided, instructor-dominant discussions about teaching writing to Latino/a students. Instead, we want our students to tell you, and previously published accounts, what they think about learning about writing and about reading.

In the rest of this article, we review the relationship between self-efficacy, writing, and WAW pedagogies to introduce why listening to students’ experiences with a WAW curriculum may be a particularly important first step for writing researchers working in HSIs and other minority-serving institutions. After outlining our methodology, we move into a discussion of our key findings, beginning with a collision of perceptions. UTPA students, contrary to published accounts, felt prepared for college-level work—a perspective challenged by contributive research requirements, which did not align with student expectations about what college reading and writing should be. We then discuss how our WAW curriculum created discomfort for students by demanding they learn new procedures and practices for reading and writing, thereby challenging students’ self-efficacy. Rather than overwhelming students, WAW requirements seem to be a key factor in creating a greater sense of self-efficacy. In light of our students’ discussions about themselves as “survivors” and the pattern we saw in the relationship between external loci of control and students’ sense of preparedness, we end with a call for more research with WAW pedagogies at minority-serving institutions and an example of an imperfect student document that encapsulates students’ sense of survivorship.

Self-Efficacy, Writing, and WAW

As a discipline, we accept that writing is emotional and intellectual work, and for more than twenty years, Susan McLeod has called on us to pay attention to students’ work and their “affective reactions to writing and to themselves as writers” (Some 427). She argues that the affective dimensions of writing might allow us “to know more about how we can help students value their own abilities” (Some 430). One way to help students, for example, can come from knowing how they find value in their capabilities and practices. McLeod has noted how students use experiences to perceive and design outcomes for learning—that is, how students use experiences to “develop a set of beliefs about the reasons for their own success or failure” (Pygmalion 372). Wanting to understand the importance of students’ abilities to evaluate their own writing skills and performances, Patricia McCarthy and her colleagues focused on students’ assessment of themselves and their abilities to write effectively. McCarthy et al. found a relationship between students’ self-evaluations, or “assessment of ‘self-efficacy,’” and their written products (465). Championed by Albert Bandura, self-efficacy is a social cognitive theory that suggests that what we believe we can do matters more than our actual ability to complete a task. That is, we may know that a certain behavior will get us the outcomes we want, but we also must believe that we can execute the behavior that will get us that outcome. The role of self-efficacy in students’ ability to determine personal capability should be of particular concern for WAW instructors because students often enter writing courses knowing, they think, everything there is to know about how to read and write. But the WAW approach changes the nature of the outcome. Focused on declarative and procedural knowledge about writing and reading, our curriculum no longer aligns neatly with previous coursework. Thus, students’ self-beliefs about who they are as readers and writers may cause interference, affecting the behaviors and practices students will attempt as well as “how long they will persist in the face of obstacles” presented by WAW courses (McCarthy 466).

Across the disciplines, scholars have used efficacy to assess students’ confidence that they possessed specific writing skills or that they could complete particular writing tasks. Scholars have even examined how efficacy might predict a student’s writing performance (Pajares; Pajares and Johnson; Meier, McCarthy, and Schmeck; Zimmerman and Bandura). We now know that students will write if they know their behaviors, or practices, will produce the desired outcome, a written product in this case, and if they evaluate themselves as capable of exercising the writing practices. As McCarthy et al. suggest, “In this way, a student might know what is expected in an effective piece of writing and might even know the steps necessary to produce such a piece. But if the person lacks the belief that he or she can achieve the desired outcome, then effective behavior will likely not result” (466; emphasis added).

Mariano, a student in Moriah’s very first WAW course, didn’t believe he could achieve the unfamiliar outcomes of the course. He completed the first major writing project in Moriah’s second-semester required writing course (a theoretical reflection about the purpose of research and writing in higher education) but disappeared as students began drafting research questions and developing primary research instruments.{2} Sitting in Moriah’s office two weeks later, he told her he wanted to drop the class. She asked him why, and he rattled off a list of excuses, ending with the excuse that he didn’t have any “good” ideas for the major research project. Moriah and Mariano finally agreed that researching why he wanted to drop the class—what about the reading and writing requirements were making him and others want to quit—was a sound project. He conducted the primary research and wrote the final report. Interwoven into Mariano’s final report was a narrative about his desire to drop the WAW class and his rationale for why other students he spoke to dropped the course:

After the main project was assigned, I left the classroom just stumped. I didn’t know what to write about or what to research. Then I started thinking about dropping the class. Yes, this very paper was the sole reason why I thought I might drop this class. I believe students drop such classes because they are intimidated by the demands, or don’t feel confident enough that they can maintain “the daily grind” that such a class demands out of a student. Especially with the high school lifestyle habits rolling over to the university level, many students, like me, must feel like they lost control of their schedule after procrastinating for so long. Not having the control anymore made me feel like there was no option left for me. As I kept procrastinating on this project, the thought of dropping this class began to dawn on me even more: “Maybe I’ll just drop this class, and next year I’ll take a bullshit 1302 class like my friends are taking; I wouldn’t have to worry about coming up with a stupid idea for this project, thus removing the stress of failing this class.” (emphasis added)

By suggesting that UTPA students were intimidated by the requirements, Mariano projected (or reflected) what we think is an emerging issue for students completing WAW courses at UTPA. Surrounding those of us teaching writing with Latino/a students at HSIs and beyond are “rhetorics of lack,” which may not only influence our perceptions of students’ abilities but may also seep into students’ perceptions about their abilities. And, as we suggest below, listening to the students’ experiences of learning to write under a new curriculum may be particularly important for all teachers and students undertaking a WAW approach.

Methodology

In the fall of 2009, two tenure-track rhetoric and composition faculty members, four 3-year lecturers, and four departmental TAs launched 23 sections of WAW in our department with the support of our WPA. We typically begin the two-semester, first-year writing sequence by asking students to understand something new about the practices and relationships between reading and writing; though we don’t have a standardized curriculum, those of us teaching WAW use the first course in the sequence to help students learn something new about their processes and practices as a way to find their own entry points in unfamiliar readings; we often use discussions about the purpose and perception of first-year writing as a starting point. In the second-semester of the course sequence, students extend their understanding of (academic) writing and research conversations by developing large-scale investigations into writing-related issues they might face as (college) writers. While approaches vary more in the second semester—Moriah’s courses, for example, explore the role of undergraduate contributive research in higher education—we all ask students to engage in meaningful, research-driven writing projects that are often extensions of the first-semester course conversations: empirical research projects driven by students’ questions about and interests in the nature and practice of writing and/or writing concepts. Embedded in our students’ research and writing for WAW courses have been discussions about what this curriculum asks of students and how they are being pushed to create new academic identities. By reading, discussing, writing, researching, and reflecting on that which was familiar—reading and writing—students are reassessing their literacy practices, particularly who they believed themselves to be as writers and what they thought they could accomplish in a writing course.

During the 2009-2010 AY, we collected 177 pilot surveys from students enrolled in WAW-focused first-year composition courses, and in 2010-2011 AY, we collected 337 surveys (see Appendix 1). The survey was distributed electronically at the end of the semester through a third-party site and prior to the submission of final portfolios. We hoped to capture students’ perceptions about their reading and writing abilities before enrolling in the course, the challenges they faced while taking the course, and what they felt they learned once they had completed the course. After completing demographic questions, the survey asked students to reflect on four areas: writing attitudes and influences, reading attitudes and influences, attitudes toward the course, and perceived outcomes for the course. Students responded to multiple-choice (5), open-ended (5), yes/no (1), and Likert-scale (6) questions. The third-party site hosting the survey quantified the closed-ended question results into percentages; we coded the open-ended questions on our own. When reading the questions, we identified repeating patterns within student answers, collapsing similar responses into larger categories. For example, we knew from hallway chatter that students were talking about our WAW courses with other students; we wondered how many were talking with friends or family about their classroom experiences (Question 14) and what they were talking about with them (Question 15). We identified twelve patterns in student conversations, ranging from liking the class content to how different it was from high school English.

To contextualize survey information, we also collected end-of-course reflections (see Appendix 2). Students in our first-year writing program typically submit final portfolios, and a key part of these has been the final reflective cover letter. The WAW instructors provided us with these reflections after removing identifying information (student name, instructor, course and section number). In 2009-2010 AY, we collected twenty-two samples, and another twenty in 2010-2011 AY. Because we did not pre-select students for the reflection samples, we cannot correlate their reflections to final course grades, but our goal with the research was not to track student success in individual courses with individual instructors; instead, because we were all new to the curriculum, we wanted to capture students’ experiences.

Our combined data does not allow us to make definitive statements about how all students enrolled in WAW courses at UTPA feel about their literacy practices; however, our two-year study suggests that students’ struggles in the course were tied to their perceptions of themselves as readers and writers. The course readings and writing assignments do not appear to be miring students down in discipline-specific discourse, but the course demands that students look at themselves as writers who have writing practices; that is, the WAW course demands they take themselves as readers and writers seriously.

“I Got This. Oh. Wait. No. No, I Don’t.” WAW Challenges Self-Efficacy

According to survey data, a majority of UTPA students do not identify as under engaged or even under prepared. Instead, when asked to reflect on what they knew about writing before the class began, the pilot data revealed 69 percent of UTPA students indicated they were either “strong” writers who knew “a lot” about writing or were “okay” writers who knew “something” about writing. These numbers were similar to those reported in the 2010-2011 AY results, in which 78 percent self-identified as “strong” or “okay” writers. Students were also fairly confident in their ability to read. Seventy-nine percent of pilot study participants indicated they were “strong” or “okay” readers; the following year, the percentage was up: 90 percent indicated they were “strong” readers or “okay” readers.

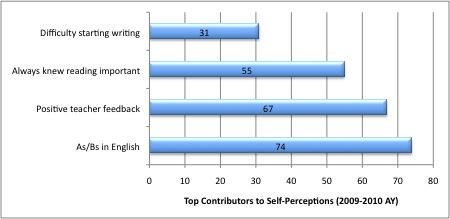

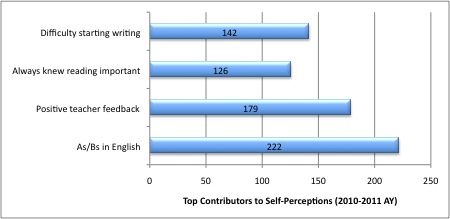

To understand what contributed to students’ self-perceptions, we asked them to identify three factors contributing to how they thought of themselves as readers and writers (see Figures 1 and 2). In both the reading and writing categories and in both years of our study, grades were the top contributor to students’ perceptions of their literate abilities. Good grades, which in our multiple-choice question meant As and Bs in English, combined with positive feedback from teachers to make up the top contributors to students’ perceptions. These two factors allowed UTPA students to believe they already “[knew] what behaviors [would] produce desired outcomes.” They “evaluate[d] themselves as capable of performing the necessary behaviors” to succeed in a college English class (McCarthy et al. 466).

Figure 1. Question 7 and Question 11. 177 total surveys.

Figure 2. Question 7 and Question 11. 337 total surveys.

For UTPA students, their positive self-assessments hold up only until they are required to do something that they did not originally anticipate as part of the college writing experience. Using their past English classes to explain their expectations, students told us in written reflections that they were used to learning about “books” or “grammar” but not “about writing and reading.” Students anticipated an “easy class,” in which they could “just slack off and not do anything.” Others expected they would complete “a lot of boring reading and a lot of boring writing.” Still others thought the course might offer “an opportunity to . . . learn what I haven’t learn[ed] before.” While telling us about their expectations, a pattern quickly emerged. Students seemed to believe the work they were encountering could not be done because, as one student suggested, “Before I got into college I never took writing or writing papers seriously so I started off behind struggling [and] wonder[ing] if I might need to drop the course because I thought that the class would be entirely too much for me.” Or, as another suggested, “at one point particularly within the first week I felt like dropping the course because I thought the workload was a bit extreme.” As we listened to students’ reactions to and experiences in the curriculum, we began to wonder how much of their discomfort with the course was connected to perceived concerns about performance and their previous external markers of achievement.

The demands of the WAW course and students’ self-perceptions about the purpose of a writing course collided when the reading materials and workload challenged their ideas of what kinds of reading and writing they were really capable of doing. This collision seems to be tied to the course requirement that students not only read the texts but work to ask their own questions of the texts (as a means of response). As Eric wrote,

I was never able to read an article and been able to find a question I had and then answered the question myself. . . . I really don’t like reading long articles plus then having to come up with a question and have to answer it myself. How was I supposed to come up with the answer to the question I asked? If the reason I asked the question was because I didn’t know the answer in the first place. (emphasis added)

There is a logic and legitimacy to his question; why would we, the instructors, ask students to ask and answer their own questions? Hector seems to have the answer:

Since the first day I learned that reading for content was not going to be enough to succeed in the course. I was never familiar with the word rhetorical but now I needed to read rhetorically which will be one of the skills that will help me not just in this course but in most of them. . . . I was so used to just scan[ning] through the paper that reading it with[out] the intention of actually understanding the text. All the time the question[s] were provided and that’s why I only looked for the answers but now I needed to make the question and in order to come up with an interesting question I needed to read the whole text but more than read it, understand it. (emphasis added)

WAW courses encourage students to wrestle with writing concepts as a means of doing contributive research, and for many UTPA students, our course seems to be the first time this has been expected of them. Without the instant gratification of daily grades or six-week reports, there was no immediate measure of students’ reading and writing abilities except for their own assessments, and students appear to have lost their beacon of success. Our students likely expected college writing to directly extend from and build on the testing culture of the Rio Grande Valley. As Charlton notes, in high school, students write narrative responses to prompts about a time they were afraid, and they are also reading literary texts to find the right answer. By the time they enter the WAW classroom, the “kind and amount of reading, thinking, and writing we ask them to do seems radically at odds with their past experiences” (6). Even though grades were one key way students understood who they were as readers and writers, few wrote about grades in their reflections. Instead, most were focused on writing about the confidence they gained in themselves as readers and writers. The reflections assigned by WAW professors ask students to reflect on the Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs), and we acknowledge that in the first-semester course, gaining confidence is a key outcome. However, we don’t think this dilutes what the students learned in the WAW course because the WAW curriculum offers unique, meta-cognitive challenges for students, including a focus on improving students’ awareness about their writing habits and processes. In fact, the design of the WAW course addresses three psychological variables that contribute to self-efficacy: anxiety, locus of control, and cognitive style. Bandura suggested that anxiety could be an indicator of low self-efficacy; in the case of writing, this “intense feeling of uneasiness” could also manifest as “distress experienced in anticipation of writing” (McCarthy et al. 466-67). Locus of control relates to the beliefs students hold about whether the “rewards and punishments in their lives are controlled by themselves or are controlled by external factors such as fate, luck, or other people.” In the context of self-efficacy, cognitive style refers to the thoughtfulness of students; these students will retain information more easily, think abstractly and make meaningful connections between sources, and are, thus, capable of “more accurate self-evaluations” (467).

Students found themselves in a strange position because so much of the WAW course is focused on meta-cognition, on students’ ability to evaluate their past reading and writing patterns to identify literacy practices that should be adapted, adopted, or alienated (see Rumsey). As Rose noted, the WAW class “focused on how we were taught, [and] the effect [of] how we were taught [how it] is affecting us presently, and trying to explain our questions on reading and writing.” Rose recognized the changing purpose of the class, and while the surveys and reflections do not provide data about pre-writing anxiety, students wrote about their anxiety in the course, and as we’ve already noted, this often began on the first day of the semester. Fernando, for instance, remembered being told on the “first day” that all of the course work would “build up [to] the final research” project. Just the discussion of sequenced reading and writing assignments caused him anxiety: “Once I hear[d] all this I started to get scared since I had [never] done a research of this type and it seemed that I was not going to be able to perform these tasks and probably end up giving up.” Before he has read anything, Fernando determined that he couldn’t do the work.

For Samantha, the anxiety she felt was directly linked to the locus of control. Too many hours and too many reading assignments were causing her to lose confidence: “But as the semester progresses the confidence meter swooped down to [a] -12. [Why?] Well maybe it was the overwhelming 17 hrs of classes I was taking this semester. Or the overpowering amount of reading we had to do.” Samantha’s plunging confidence meter suggests she, too, felt like an okay reader and writer before encountering the WAW course demands. For Victor, the WAW demands directly challenged his previous understandings of himself as a writer: “I did not know what you the teacher would expect of me in my writing. I was always taught to write for the teacher, so I feared that everything at that point was wrong and that I was going to fail miserably.” Victor’s admission reveals that for some students, the locus of control was not simply tied to grades or teachers’ positive (or negative) feedback but to teachers’ expectations for performance. The meta-cognitive effort required to focus on practices and learning seems to have caused a shift in students’ locus of control.

WAW Demands New Practices

Students entering UTPA’s WAW courses had a positive sense of self-efficacy based largely on good grades and positive teacher feedback. When they encountered an unanticipated curriculum with unexpected requirements and demands, however, they begin to question their abilities, largely because their progress and performance was now about practices, not just products. Their previous measures of success (external loci of control) no longer helped them. Anxiety set in. This was especially true for the reading requirements, and we could see this shifting happen—the tectonic plates of the class and the students started to move. The initial ripples were furrowed brows, shuffling in seats, and increased absences. It was as if their academic plates (or identities) fell victim to the pressure of our questions: what can they do? what could they do differently? how do they do that? Students assumed and expected that what they were able to produce mattered most in the course, so they began the semester trying to reproduce materials from their old practices, never considering the possibility that they might need to revise their reading and writing habits. The discomfort students experience when the content of the course requires a new practice for thinking about reading and thinking about writing interests us because this discomfort seems to mire students down in their own thinking about reading and writing rather than serving as a jumpstart for exploring new practices.

About a third of UTPA students enrolled in WAW courses reported feeling stressed by the daily work of the class (32 percent in 2009-2010 AY; 31 percent in 2010-2011 AY). Students typically blamed the stress on the high-school-to-college transition. They wrote about being “stuck” in “high school mode,” which, according to them, “did not require much effort.” They wrote about how “high school and middle school efforts won’t hack the college level work [they’ve] been given.” For Esperanza, feeling lost and confused wasn’t just about being in a WAW course:

Being an entering freshman, freshly out of high school, I was sort of lost and confused with the courses I was going to take and had no clue what they were about. . . . I was now doing everything on my own without the help of anyone, like how I was accustomed to in my [high school] years. Like the help from familiar teachers and counselors. . . . I was always being told how laid back college really is so I thought “this is going to be a piece of cake.”

For Esperanza, her self-perceptions of what it meant to be in college were challenged by the curriculum of the WAW class, and she was not alone. The first half of the semester was especially painful for students—many reported feeling unprepared for the course even though, again, they indicated feeling like okay and strong readers and writers. (Interestingly enough, in the two years of our study, only around 10 percent of respondents reported they had given up on the reading and writing assignments—a low percentage in light of the argument that WAW overwhelms students with disciplinary readings.)

Students did report the absence of a “reading habit,” always “feeling tired,” facing multiple time constraints, and even dealing with disinterest in the course content. Lisa wondered if the first reading of the semester was a scare tactic: “I thought to myself, ‘Is she making us read this article first so we can get scared and drop?’ That made me laugh, why in the world would a Doctor in English make any of her students read something that did not make any sense and not help us students accomplish our course objectives.” Clearly, scholarly articles from journals like College Composition and Communication were not a part of students’ vision of first-year writing, and, as we’ve already discussed, their expectations were likely grounded in their high school experiences of reading short stories, novels, and/or creative nonfiction (or any kind of literature). One thing we couldn’t quite understand was why so many students were shocked by the length of the academic articles. None were as long as a novel or play, and some were of similar length to a typical short story. The more reflections and open-ended questions we read, however, the more clear it became that resistance was to content not length. Esperanza wrote,

When I received my first article, I was shocked at how long the article was with such little [font]. I knew right away I wasn’t going to be able to read all of it. I made the effort to read it and try to comprehend it to at least get myself accustomed to reading these long texts. Pushing myself to read these long texts helped me to open my mind and be able to read the college level articles. (emphasis added)

Like Fernando, Esperanza assessed her ability to complete the course work before attempting it. Students would simply scan the required pages. Sandra’s reflection suggests the students would print out the articles from the library databases and simply be struck with anxiety: “The first time I printed the article assign, I got scared because I couldn’t believe I had to read a long, long article by one or two days.”

Students weren’t trying to understand the purpose of their reading and writing assignments, and they weren’t making the explicit connections between the content of the class and what they were being asked to do. When asked why they would not recommend the course to a friend (Question 19), a majority said they would not tell a friend to enroll in a WAW course because the class involved a lot of work and/or was time consuming. Students were intimidated by the “long the article[s],” but they were also wondering why they were reading them: “Why would I want to read something that was writing for teachers to read and not me, and if that is the case, why do the teachers [want] us to read that?” Students directly challenged us to reconsider the reading requirements because, after all, “a majority of the class are in-coming freshman that aren’t use to reading on an every day [basis].” Buried in student complaints were explanations about what they were doing once they decided the old methods weren’t going to be enough. They explained what it meant to “kick it up a notch.” For example, one student’s explanation focused on phases:

After procrastinating and leaving it to the last-last-last minute, I had to read it three times; the first was like I was reading a foreign language. The second was to clear up some definitions I had to continue to reread a third time until it was clear. The underlying message began to unravel but I was still unsure of what to think of it all.

This student’s explanation is not earth shattering, but it does reveal what we can learn when we listen to our students, when we let them tell us what it’s like to learn how to read and write under the new condition of a course content fully aligned with disciplinary knowledge.

If our students were “mired down” in the readings and discomfort caused by them, they weren’t drowning. The reading requirements are a key criticism of WAW, and initial feedback to the approach explicitly addressed its use of scholarly and disciplinary-specific texts as required reading. When speculating about the differences between attitudinal changes and behavioral changes in WAW students, Kutney asked readers to recall a student discussed by Downs and Wardle in the College Composition and Communication article. Kutney uses Jack’s struggles as a reader and writer to make an aside about “students potentially overmatched by the content of Introduction to Writing Studies” (278). In their response, Miles et al. are concerned that WAW might have “perhaps unwittingly—fallen into a problematic synecdoche in which one course stands in for the whole of the discipline” and that by not focusing on “procedural knowledge” the WAW course mires students down in “specialized discourse” instead of teaching the practices and strategies of the field (504).

Challenging Kutney and Miles et al., Barbara Bird insists that a number of researchers have found that “not only can [our] students read and understand far more than we may realize, but also that grappling with difficult disciplinary texts . . . promotes greater reading power than what could be achieved by reading the kinds of essays found in the vast majority readers used in FYC courses” (167). By the end of the semester, a majority of our students seem to reinforce Bird’s point about reading power and, we would suggest, self-efficacy. Students are succeeding because they struggled to complete those initial reading and writing assignments. By the end of the semester, 68 percent of students report feeling confident in their ability to make connections between reading and writing assignments, and 42 percent feel confident in their ability to ask questions about the purpose of a reading assignment they are given. In the 2010-2011 AY survey, 72 percent of students reported feeling confident in their ability to make connections between reading and writing assignments. Forty-three percent of students reported being confident in their ability to ask questions about the purpose of reading assignments, and the same number of students were confident they could read scholarly articles for academic writing assignments.

Our study suggests there are important rewards for students if they can persist through the course, but we clearly need to work harder at helping students separate their routinized practices—those they perfected in high school and understood through external loci of control—from personal or intellectual ability because, as Dale Schunk argues, “[l]ow self-evaluations will not necessarily diminish self-efficacy and motivation if students believe they can succeed but that their present approach is ineffective” (164). Like other efficacy researchers, Schunk contends that students “who feel efficacious for learning or performing a task participate more readily, work harder, persist longer when they encounter difficulties, and achieve a higher level” (161).

The transition from high school to college is a theme in Joe’s reflection. He admits to spending at least half the semester getting “over not being in high school anymore” and letting it sink in that he was “in college now.” For Joe, not being in high school meant he had to “finally start to read and study for the fi[r]st time.” Like so many first-time college students, his expectations for reading and writing were grounded in previous experiences and abilities. Joe entered the classroom sure his “writing and reading skills were ok[ay].” But the requirements for the course did not align with his abilities:

[L]ooking back I see that in high school I was taught to just answer the question asked and elaborate a bit on it for the paper but after taking your class I learned that you have to ask yourself questions about the topic and try to answer them as [well] as you can. Not just write and going on and on without a purpose.

In discussing his previous experiences with reading and writing, Joe acknowledges that he still thinks he’s an “ok[ay] writer,” but his work in the course has altered his perceptions; he’s begun to see that the reading and writing tools necessary for college-level work are driven by his own inquiry-based responses (points confirmed by other researchers, including Sommers and Saltz; and Kantz). We also hear Joe beginning to recognize that his earlier feelings of ineffectiveness were not linked to ability but to practice; rather than being overwhelmed by his self-perceptions, the writing assignments in the course gave him a way to try out something new. Like 41 percent of the students in our pilot study, he feels more capable of making adjustments to his writing process.

Other students experienced similar changes in perceptions about their writing processes. Gabby knew the WAW course was hard, but she also notes it gave her an “opportunity for success.” In terms of writing, she finally understood something: “the first draft is not going to be the one you are going to be turning in it takes several drafts and a lot of review after making a decision on what is the final paper.” Gabby’s new understanding about the nature and purpose of drafting was also echoed in the survey. At the end of the semester, 82 percent and 85 percent of students reported understanding reading and writing as complex activities, not just skills. For Jose, the complexity of reading and writing means getting “used to the idea of a writing process, rather than a writing task.” He also has learned that future writing assignments will mean a new practice: “In future writing assignments I really want to focus on what I want to go through while learning new information and formulating thoughts on it. I will ask myself questions like, why do I want to learn this? Or how is it important to where I am in life?” When students tell us they need new tools and have questions they’ll ask before and during their writing process, we hear them saying they’ve found a new, internal practice for writing—one that may give them a different measure of self-efficacy than external markers, like grades. Like Jose, Virginia gained a new methodology for writing. She admitted that for “writing to come a little easier to” her, she would “need to make the effort to come up with a question or topic,” something she was “truly interested in.” Virginia adopted this new practice after making “the connection and relationship between what [she] was reading and what [her] interviewees had to say, and also what [she] had to say.” In writing up her contributive research project and synthesizing primary and secondary data, Virginia understood that the complexity of a writing assignment means she can do different things with her sources—that she can have different kinds of sources.

The complexity of the writing tasks and students’ ability to complete them: these stories repeated again and again as students told us how they met the challenges of the course. Students told us the class gave them “much more confidence as a writer and the ability to be a good writer,” and about the changes that came from their writing projects:

This project helped me transform from an unconfident writer to a reflective, confident writer. . . . I feel a sense of accomplishment. . . . I strongly believe that this 1301 class has given me the confidence to read and write effectively, it is a transformation that has made me a rhetorical[ly] aware writer and reader. . . . I will use both content and context strategies to become a better writer.

This student was not alone; 73 percent and 84 percent of students agreed they were more confident in their ability to produce academic writing.

Some Thoughts on WAW and “At Risk” Students

Bandura suggests there is no easy link between performance and self-evaluation. In fact, “evaluations about one’s abilities (efficacy expectations) develop as individuals attempt a behavior and receive feedback about the quality of their performance. Furthermore, efficacy expectations lead to performance, followed by feedback and further development of expectations” (466). First interpreted by UTPA students as an overwhelming and difficult workload, the WAW courses became opportunities to improve reading and writing skills and change self-perceptions. The readings we asked students to complete dominated their reflections, and we suspect this pattern comes from the relationship between content and practice in WAW courses. Students are reading original research in writing studies to contribute to the conversation and conduct original research; yes, they are gaining content knowledge of the discipline, but in our courses that information is useful if and only if students can gain something from it for themselves. The readings are designed to give them new tools to ask the questions they have about their writing processes and practices.

UTPA students reported they would recommend this course to their peers because they believed the course was helpful and would improve reading and writing abilities. In his review of self-efficacy literature, Pajares suggests that students’ “writing confidence and competence increase when they are provided with process goals (i.e., specific strategies they can use to improve their writing) and regular feedback regarding how well they are using such strategies.” Researchers have also “demonstrated that instruction in self-regulatory strategies increases both writing skills and self-efficacy” (147). Students leaving our WAW courses report feeling confident in activities that were initially overwhelming and frustrating, and they identified positive gains in their understanding of writing as a practice because the course focused on developing their meta-awareness: the primary content of the course is their understanding of and experiences with writing; by talking about the theories behind the practice, students have the chance to reflect on what they know about writing and how they do writing.

By surveying students and collecting their reflective writings, we came to understand, in small ways, students’ affective encounters with a WAW curriculum. By suggesting that students might be intimidated by the requirements, Mariano revealed what we think might be an issue for students completing WAW courses at UTPA: Latino/a student self-efficacy at Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) and beyond are surrounded by “rhetorics of lack,” which may affect the students’ locus of control when encountering a new curriculum. We do not have data that confirms that our students are familiar with published accounts of their preparedness, and this is the next step in understanding the effects of WAW on Latino/a students’ efficacy. However, acknowledging published perceptions and personas may be particularly important for teachers and students undertaking a WAW curriculum. In our case, we do not deny research that suggests Hispanic students are more apprehensive about their writing and have lower writing self-efficacy rates than their non-Hispanic counterparts (Pajares and Johnson), and as Pajares argues, “the lower self-efficacy beliefs of minority students provide one explanation for why many of them become and remain ‘at risk’” (151).

We began this study, in part, because the public conversations surrounding WAW, we feared, might make faculty at institutions with high at-risk populations, including but not limited to HSIs, nervous about experimenting with the approach. Our data suggests just the opposite: students who complete the course seem to have an increased sense of self-efficacy towards academic writing and a shifting academic identity because of newly acquired practices. The philosophical and pedagogical goals of the WAW classroom, namely its focus on meta-awareness about a student’s individual experiences and writing practice, can help students who are struggling to succeed because “[p]eople who harbor self-doubts about their capabilities are easily dissuaded by obstacles or failures. Those who are assured of their capabilities intensify their efforts when they fail to achieve what they seek, and they persist until they succeed” (Zimmerman and Bandura 848). WAW may initially dissuade students of their abilities, but it is the experience of working with content about writing that allows students to develop new practices and self-perceptions.

In “Some Thoughts about Feelings,” Susan McLeod focused on students’ affective reactions to writing. In particular, she considered how student motivation, their “inner impulses or drives toward some goal,” was affected by experience-based beliefs and factors outside themselves. These “extrinsic motivating factors,” such as grades or the desire to please a teacher, “are less effective than internal motivating factors in terms of student learning” (429). In addition to motivation, McLeod considered how beliefs impact student perceptions of themselves as writers. Acknowledging that beliefs are “convictions that are not necessarily provable,” McLeod goes on to discuss the ways in which beliefs held by students affect their performance:

Our students come to us with a great many beliefs about writing which diminish their perception of their own skills as writers. Some of these are general cultural beliefs: good writers do not struggle but wait until inspiration visits; writing skills equal editing skills; the study of grammar will make you a better writer. But they also come with beliefs about themselves as writers. (429)

Of particular interest to McLeod is the issue of locus of control, how students perceive their successes and failures as writers as being attributed to an external locus (luck, teacher) or an internal locus (personal capabilities), and she explores these “non-cognitive aspects of writing” to advocate for metacognition, or “knowing about knowing” (433). Citing Lester Faigley, McLeod notes research that indicates that an increased awareness about one’s own writing process may help students self-monitor their own writing activities and emulate the models of more experienced writers, particularly in terms of the emotional states involved in composing (433).

We need to know more about WAW courses. We need to understand what motivates some students to stay engaged in the class and what motivates others to drop, to know about students’ internal dialogues that (seem to be or) are working against the goals of our curriculum, and to encourage students to see themselves as scholars and writers. We are calling for additional research with WAW, and WAW at minority-serving institutions in particular, because, as Pajares notes, a “focus on students’ self-beliefs as a principal component of academic motivation is grounded on the assumption that the beliefs that students create, develop, and hold to be true about themselves are vital forces in their success or failure in school” (140). The absence of student voices has implications for pedagogical approaches undertaken in HSIs and other institutions with similarly defined “at risk” student populations because too little research “has examined university Latino students’ opinions on concrete pedagogical and methodological considerations in the contemporary American classroom that affect their classroom participation” (Brown 98). In fact, our research challenges the “oft-used, albeit erroneous, model of deficit thinking which proposes that Latino students and their families have defects or deficits in their value system, parental skills, or both, that detract from the learning process and students’ academic performance” (Brown 102; emphasis added).

When we listened to our students, the initial deficit talk was not tied to their ability but, instead, to the external factors they used to assess their own preparedness. As they talked to us and to each other, in the classrooms and in the hallways, what quickly emerged was a new attitude, one that allowed them to challenge the ideas circulating about them and about WAW. When the course was complete, students talked about completing challenges they previously were unwilling to attempt. In high school and in her non-WAW 1301 course, Sarah “wanted to stick to thinking in ‘simple’ terms.” But, at the end of her WAW, she knew her accomplishments mattered:

Through the obstacles I have overcome and the hurdles I have jumped to reach the finish line of this race, I am happy I was one of the “survivors,” (as one of my class mates called us) from the starting participants who began. . . . I know with the accomplishments, though they may not be difficult in another person’s eyes, have made me discover what I am capable of, if only I set my mind to stick to what has been set before me.

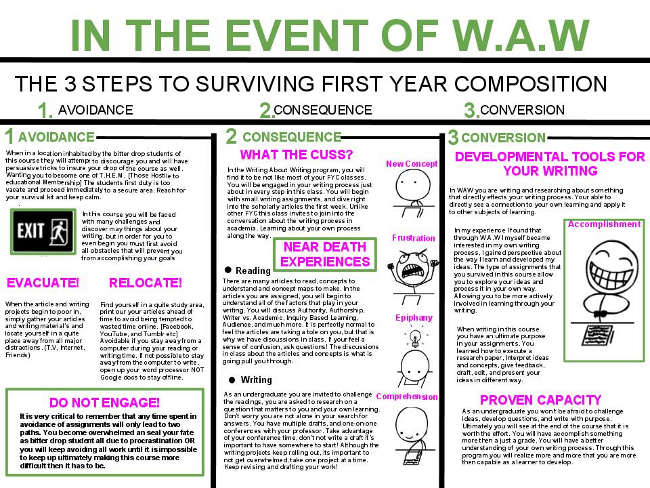

The fact that our students call themselves survivors and that they want us to print t-shirts proclaiming “I Survived WAW” speaks volumes about the curriculum for us. It is rigorous. It is demanding. About week six of the academic semester, when it’s no longer new and exhaustion is creeping in for students and for us, we often wonder why we use this approach. The WAW classroom may feel, at first, like a zombie apocalypse—something to be survived (see Appendix 3). If you keep moving, but not too fast, you just might make it to the other side. But, our students aren’t merely surviving. They leave the course unafraid to question ideas, gaining more than a grade: “Through this program, you will realize more and more that you are more than capable as a learner to develop.” We couldn’t say it any better.

Appendices

- Appendix 1: Student Survey Instrument (PDF)

- Appendix 2: Student Reflections Prompt (PDF)

- Appendix 3: Public Document designed by Angelica Nava

Appendix 3: Public Document designed by Angelica Nava

(Click on the image to view a larger version.)

Notes

- In his blog post, “New Year, New Semester, New Book,” which accompanied the launch of the Writing about Writing textbook, Downs wrote, “I’m never completely comfortable being involved in a ‘movement’—I’m not a movement kind of guy, generally. But I do think that’s how a lot of us advocates of WAW would describe the approach and its growing use: a movement in Composition.” In our hallways at UTPA, we’ve been using the language of movement to describe our belief in the power of the course to positively impact our students and our professional identities. (Return to text.)

- Students quoted in this piece gave instructors permission to quote from their writing for research and publication purposes. When granted permission to use the students’ real names, we have done so. Other students are referenced by pseudonym. We have not altered the student writing, except where noted with editorial brackets. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Bandura, Albert. Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review 84.2 (1977): 191-215. Print.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Logan: Utah State UP, 2007. Print.

Bird, Barbara. Writing about Writing as the Heart of a Writing Studies Approach to FYC: Response to Douglas Downs and Elizabeth Wardle, ‘Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions’ and to Libby Miles et al., ‘Thinking Vertically.’ College Composition and Communication 60.1 (2008): 165-81. Print.

Brown, Alan V. Effectively Educating Latino/a Students: A Comparative Study of Participation Patterns of Hispanic American and Anglo-American University Students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 7 (2008): 97-118. Print.

Carter, Shannon. Writing about Writing in Basic Writing: A Teacher/Researcher/Activist Narrative. Basic Writing e-Journal 8-9 (2009/2010): 1-16. Print.

Charlton, Colin, and Jonikka Charlton. The Illusion of Transparency at an HSI: Rethinking Service and Public Identity in a South Texas Writing Program. Going Public: What Writing Programs Learn from Engagement. Ed. Shirley Rose and Irwin Weiser. Logan: Utah State UP, 2010. 68-84. Print.

Charlton, Jonikka. Seeing is Believing: Writing Studies with ‘Basic Writing’Students. BWe: Basic Writing e-journal 8/9 (2010): 1-9. PDF. Web.

DeJoy, Nancy. Process This: Undergraduate Writing in Composition Studies. Logan: Utah State UP, 2004. Print.

Dew, Debra. Language Matters: Rhetoric and Writing I as Content Course. Writing Program Administration 26.3 (2003): 87-104. Print..

Downs, Douglas. As If We Took Them Seriously. Write On: Notes on Teaching Writing about Writing. Bits: Ideas for Teaching Composition (Bedford/St. Martin’s), 26 May 2011. Web. 8 Aug. 2011.

---. New Year, New Semester, New Book. Write On: Notes on Teaching Writing about Writing. Bits: Ideas for Teaching Composition (Bedford/St. Martin’s). 20 Jan. 2011. Web. 8 Aug. 2011.

---. Response to Miles et al. College Composition and Communication 60.1 (2008): 171-75. Print.

Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisioning ‘First-Year Composition’ as ‘Introduction to Writing Studies.’ College Composition and Communication 58.4 (2007): 552-84. Print.

---. What Can a Novice Contribute? Undergraduate Researchers in First-Year Composition. Undergraduate Research in English Studies. Ed. Laurie Grobman and Joyce Kinkead. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 2010. 173-90. Print.

Kantz, Margaret. Helping Students Use Textual Sources Persuasively. College English 52.1 (1990): 74-91. Print.

Kutney, Joshua. Will Writing Awareness Transfer to Writing Performance? Response to Douglas Downs and Elizabeth Wardle, ‘Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions.’ College Composition and Communication 59.2 (2007): 276-280. Print.

McCarthy, Patricia, Scott Meier, and Regina Rinderer. Self-Efficacy and Writing: A Different View of Self-Evaluation. College Composition and Communication 36.4 (1985): 465-71. Print.

McLeod, Susan. Some Thoughts about Feelings: The Affective Domain and the Writing Process. College Composition and Communication 38.4 (1987): 426-35. Print.

---. Pygmalion or Golem? Teacher Affect and Efficacy. College Composition and Communication 46.3 (1995): 369-86. Print.

McMillan, Laurie. Rev. of Writing about Writing: A College Reader. By Elizabeth Wardle and Douglas Downs. Composition Forum 24 (Fall 2011). Web.

Meier, Scott, Patricia R. McCarthy, and Ronald R. Schmeck. Validity of Self-Efficacy as a Predictor of Writing Performance. Cognitive Therapy and Research 8.2 (1984): 107-20. Print.

Méndez Newman, Beatrice. Teaching Writing at Hispanic Serving Institutions. Teaching Writing with Latino/a Students: Lessons Learned at Hispanic Serving Institutions. Ed. Cristina Kirklighter, Diana Cárdenas, and Susan Wolff Murphy. Albany: State U of New York P, 2007. 17-36. Print.

Miles, Libby, et al. Thinking Vertically: Commenting on Douglas Downs and Elizabeth Wardle’s ‘Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions.’ College Composition and Communication 59.3 (2008): 503-12. Print.

Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness. Stats at a Glance: Fall 2010. The University of Texas-Pan American. Web.

Pajares, Frank. Self-Efficacy Beliefs, Motivation, and Achievement in Writing: A Review of the Literature. Reading & Writing Quarterly 19 (2003): 139-58. Print.

Pajares, Frank, and Margaret J. Johnson. Self-Efficacy Beliefs in the Writing of High School Students: A Path Analysis. Psychology in the Schools 33 (1996): 163-75. Print.

Ramirez-Dhoore, Dora, and Rebecca Jones. Discovering a ‘Proper Pedagogy’: The Geography of Writing at the University of Texas-Pan American. Teaching Writing with Latino/a Students: Lessons Learned at Hispanic Serving Institutions. Ed. Cristina Kirklighter, Diana Cárdenas, and Susan Wolff Murphy. Albany: State U of New York P, 2007. 63-86. Print.

Richardson, Adele. Basically, Writing about Writing Builds Confidence and Skills in Struggling Students. Write On: Notes on Teaching Writing about Writing. Bits: Ideas for Teaching Composition (Bedford/St. Martin’s). 18 Aug. 2011. Web. 28 Aug. 2011.

Rumsey, Suzanne Kesler. Heritage Literacy: Adoption, Adaptation, and Alienation of Multimodal Literacy Tools. College Composition and Communication 60.3 (2009): 573-86. Print.

Schunk, Dale H. Self-Efficacy for Reading and Writing: Influence of Modeling, Goal Setting, and Self-Evaluation. Reading & Writing Quarterly 19 (2003): 159-72. Print.

Sommers, Nancy, and Laura Saltz. The Novice as Expert: Writing the Freshman Year. College Composition and Communication 56.1 (2004): 124-49. Print.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Continuing the Dialogue: Follow-Up Comments on ‘Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions.’ College Composition and Communication 60.1 (2008): 175-81. Print.

Zimmerman, Barry J., and Albert Bandura. Impact of Self-Regulatory Influences on Writing Course Attainment. American Educational Research Journal 31.4 (1994): 845-62. Print.

Latino/a Student (Efficacy) Expectations from Composition Forum 27 (Spring 2013)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/27/student-expectations.php

© Copyright 2013 I. Moriah McCracken and Valerie A. Ortiz.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 27 table of contents.