Composition Forum 30, Fall 2014

http://compositionforum.com/issue/30/

Community through Collaborative Self-Reflection: Reports on a Writing Program History and Reunion at Stony Brook University

Abstract: This program profile examines the storied and conflicted five-decade genealogy of the Stony Brook University writing program. From the points of view of former administrators of this program who were faculty members during two of its most significant transitional periods, the authors make a case for the utmost importance of faculty community and reflectiveness, discourse-empowered advocacy, and shared governance to the well-being of postsecondary writing programs. In this context, the profile maintains a particular focus on disciplinary identity formation, including its effects on curriculum, working conditions, and placement and assessment practices.

Introduction

Before reading our profile, we ask you to stop and create your own private list of what you believe should be the goals of your writing program. After listing these items, rank them in terms of priorities. You’re allowed to have more than one item for each number. Then put this aside and keep it for later.

The co-authors both formerly held administrative positions in what is now the independent Program in Writing and Rhetoric (PWR) at what is now Stony Brook University.{1} Like so many things in the five decades that the following history spans, the names of these two entities have changed: respectively, from the Writing Program (of the English Department) and the State University of New York at Stony Brook. We offer here a history of a more than thirty-year-old program that was previously one of the nation’s most influential sites of writing pedagogy and theory, and whose story offers valuable insights into the nature of institutional identity and change.

In particular, this profile considers the ecology of institutional change, including particularly what a faculty can learn through reflection on its continuing developments, how that genealogy reveals what remains consistent, and how faculty can influence these matters and empower themselves in the process by understanding, as best they can, how and why changes occur. As these matters are both individually and collectively experienced, their narration in this form might be called a personnel essay. In fact, we contend that writing faculty must endeavor to tell themselves, each other, and external parties their own and their shared professional stories. Underlying our explorations, readers will undoubtedly find connections to the histories of their own institutions’ teaching of writing and to the development of the field of composition studies itself. This makes for much of the value of personal stories for public audiences, in addition to their value for creating solidarity, much in the same way as personal narratives and memoirs so often tell us something about our own lives as well as about the world we live in. It is partially through the accumulated narration of individual reflections that community forms, and through this development that programs empower themselves to create and advocate for positive change.

The history of a relatively long-standing program such as Stony Brook’s resembles a family’s ancestry at least in so far as contemporaries bear the direct influence of earlier generations, often unwittingly and at times unwillingly.{2} Members of new or emerging writing programs can look ahead if not back on this influence. Descendants inherit from forebears genetic traits (e.g., disciplinary training), demonstrate characteristic behavior patterns (e.g., assessment routines), and sometimes inhabit their predecessors’ same dwelling places (e.g., a building, status on campus). In these and other ways a family lineage possesses a certain degree of constancy over the ages, just as each of its generations achieves its own kind of cohesiveness through shared day-to-day activities. And yet, drastic events can impact a family, bringing in new elements both favorable and unfavorable. Professional traditions work by similar means: personnel come and go while other aspects of a writing program remain consistent over the endless cycle of semesters. But, as with families, welcome and unwelcome changes inevitably set the program off in new directions.

Nonetheless, some persistent identifying traits can still be usefully brought to light upon self-scrutiny. Just as some families periodically reflect on such diversity and consistency at reunion events in part to know more about who they are, writing programs should also collectively, regularly reflect on themselves. Taking up past issues and taking out old documents helps to make a program’s development deliberate and its identities informed. To elaborate on Barbara L’Eplattenier’s insightful point that “simply having a history creates legitimacy for contemporary work” (136), it might be said that knowing and feeling connected with one’s programmatic history enables one to promote and expand that legitimate work. Such is an effect of narrative, which Susan Miller notes at the outset of Textual Carnivals: “power is, at its roots, telling our own stories” (1); such is also an effect of archival research, as Lynée Lewis Gaillet puts it: “archives shape identity” (54).

Our experience shows that community building through collaborative self-reflection boosts faculty morale and promotes creative thinking toward mutual benefit—all welcome responses to today’s conflicted culture in higher education. This may be especially so in writing programs, where pronounced labor inequities can hinder faculty solidarity and departmental progress. Chronicling of a disciplinary culture must aspire to honesty and inclusiveness, taking into account Melissa Ianetta’s caveat to historiographers: “It is only by keeping labor central to our narrative accountings . . . that we will take advantage of all our shared histories have to offer” (70). Any narrated history varies according to the interpretive tendencies of whoever’s telling the story. This one is told by two insiders who have intermittently felt like outsiders in their own disciplinary home: A longtime contingent faculty member with administrative duties but sometimes no voting privileges (now on a tenure line) and an administrator left in the dark during the program’s most significant transformation. As seen through these lenses, this history recounts failures and successes of shared governance and self-determination, a struggle that seems central to all writing programs no matter their age or local particularities.

Our decision to formally reflect as such was prompted by a unique occasion in the Stony Brook PWR’s history. One of the coauthors, Khost, organized a reunion conference in the spring of 2010, inviting all faculty and staff, past and present, who have had an employment connection with the PWR. Called “Where Have We Been? Where Are We Going?” the event was held in the Humanities building that guests had known as their professional home at one time, pre- and/or post-refurbishment. Invitees went back to the late 1970s and attendees numbered in the dozens. Peter Elbow and Pat Belanoff, who ran the program throughout the 80s (and Pat into the 90s), were the featured speakers, but everyone who attended was encouraged to contribute memories, including a roundtable panel of nine former faculty members.{3} As past program directors in attendance, Peter, Pat, and Bruce Bashford (who directed the program for a time prior to 1982) were awarded certificates of appreciation by the University. Old photos and stories were shared, meals were enjoyed, and a faculty survey was completed—a survey that has since become quite influential in shaping developments in the PWR. The reunion provided an opportunity for all attendees to reflect on their past and present goals for the program, and it became the impetus for a number of significant subsequent developments. This profile, in a sense, represents a reflection on those reflections, and it projects the projects discussed on that day together. It also takes its place in a tradition of publications about writing instruction at Stony Brook. As we look back on these other works and on the memories and inspiration the reunion conference brought us all, we recognize a unique opportunity to consider the changes in the Stony Brook PWR within the context of the larger field of rhetoric and composition itself.

A( )typical history

Although Stony Brook was one of the first institutions to post, in 1974, a job ad with the MLA for an associate professor composition director with a corresponding research agenda (SU of NY 9), the faculty did not include such an individual for almost another decade. Such a position was to be added to a fairly large English department with forty or so tenure-track faculty. In an email, Bruce Bashford, the department’s eventual rhetoric specialist (now retired), noted that before Peter and Pat arrived, “the program . . . was housed within the English department and supervised by a junior faculty member whom the English department strongly recommended for tenure, but with no success.” We can find no available record for this departmental decision, and can only speculate that this individual had so much responsibility as to prevent him from doing sufficient research. He worked out of his ordinary faculty office with very little assistance, reading all the placement exams himself! Furthermore, Bashford recalled that for two or three years in the 70s:

there were “clusters”: a faculty member teaching the course in conjunction with, say, five graduate students. Some of the clusters worked together closely as a staff, others more loosely. Later faculty working specifically in the Writing Program [as it was called then] would teach composition, but the clusters were the last hurrah at Stony Brook for the venerable tradition that could give an incoming student a senior literary scholar as their writing instructor.

After that, TAs taught most of the writing, with “little coordination across sections,” under the direction of literature specialists (Bashford). As we look back, we recognize this as the beginnings of the gradual separation of the English department and the Writing Program.

The next step in this separation process occurred in 1977-78 when the University, not the department, not the program, mandated a proficiency exam. This decision, resulting from deliberations of a campus-wide committee, was probably a reaction to “the periodic dissatisfaction university faculty feel about how their students write” (Bashford). We will consider that exam more fully below when we talk about assessment. By that time Bashford had taken on responsibility for the program. With the help only of a graduate-student assistant, he supervised the proficiency exam and placed all the students: “We ran an operation that included more courses . . . more students, and more instructors than the rest of the English Department combined.” Bashford sometimes “took to coming in on Saturday and Sunday as well, using a ring signal with [his] wife, since students would call with business even on those days.” Such provisional efforts were not uncommon at colleges and universities throughout the country during this time, when many writing program administrators, as Kenneth Bruffee remembers, were “just coping from day to day to week to week” (Heckathorn 216).

In 1982, eight years after Stony Brook first posted its ad in the MLA Job List for a tenured faculty member to head up the Writing Program, Peter Elbow was hired. Peter was already beginning to receive widespread recognition; consequently, his arrival created an opportunity for the Stony Brook Writing Program to begin to have a national reputation. Prior to his appointment, Peter had taught at Evergreen College in Oregon, an institution with decidedly uncharacteristic approaches to post-secondary education. Obviously Peter brought that environment with him, and upon reflection, he admitted: “I was very grateful that SB offered me a chance to try to put my approach into effect in a ‘standard conventional’ curriculum. Till then, it had only been ‘Odd’ places—MIT, Franconia, Evergreen [institutions where Peter had worked previously]. People accused these ideas of only working in some kind of hothouse atmosphere—and I feared maybe they were right.” Additionally he opined that perhaps he was hired for the job because “though they needed a ‘professional’ in comp—I was less scary to them because of my strong lit background: ‘He can't make too much trouble’ they must have thought” (“Re: SB History”). Peter had, after all, already published a book on Chaucer, but it would be his last work focused exclusively on literature.

Pat arrived in 1983 to serve as associate director of writing, though she was not hired on a tenure line. Like so many others at that time who migrated from literature to composition and rhetoric,{4} she possessed a literature degree, having written a dissertation on the women of Old English literature. She had, however, worked closely with the director of the NYU program, spent a year as a writing consultant on a federal grant at Kean College in New Jersey, and returned to serve for a year as the interim assistant director of the NYU writing program, working closely with Lil Brannon and Cy Knoblauch. Her appointment at Stony Brook was not a back door way of getting another medievalist in the English department: She only began teaching some medieval courses when the department lost one of its specialists in this area. However, unlike Peter, she then continued to teach literature along with writing courses, as well as graduate courses in both medieval literature and composition and rhetoric. Thus, interestingly, as the associate director of writing, Pat had a tighter connection to the English department than the director had.{5}

When Peter and Pat took over, the English department offered three writing courses: EGC100, EGC101, and EGL 202. EGC101 was the required course; EGC 100 was a course designed for students whose placement test results indicated they lacked sufficient experience with writing; EGL 202 (notice the different designation) was an advanced writing class. A high percentage of students in EGC100 were non-native English speakers. There were usually only four sections of this class per semester; passing the course did not satisfy the University’s writing requirement. Generally, there were also four—at times five—sections of EGL202; thus EGC100 and EGL202 were in a kind of balance. Additionally, a very small number of incoming students were required to take one or more courses in the Linguistics department before taking either of the English department’s courses. There was no composition scholar in the Linguistics department, though several attempts (with the support of that department) were made to create such a line—all unsuccessful. Faculty in Linguistics were responsible for placing these students in one of four levels of composition within their own department and later certifying their competence to enter the mainstream writing program classes.

Between the end of Bashford’s directorship and the arrival of Peter and Pat, almost all writing courses had been taught by graduate students. During their first year of teaching, these students were required to attend a pre-semester workshop and a semester-long practicum, a requirement instituted in prior years. It did not, and never did from its inception, count as one of the courses contributing to the doctoral graduation requirements. Most of these students continued to teach writing courses during their second year, although some had the opportunity to teach general-education introduction to literature classes that the Writing Program administered, the intent of which (whether fulfilled or not) was to emphasize writing about literature. Many of these students returned to the teaching of writing during their fourth year as graduate students.

In 1984, the staff of the program changed somewhat. English graduate students still taught during their first and second years in the program, but the program was given funds to hire seven part-time lecturers, each teaching two courses per semester. Two or so years later, the program was granted eight graduate students from other departments. At the outset, Peter and Pat interviewed them, but after a few years of this they simply accepted the students that other departments sent over. For Peter and Pat, and for directors in other departments, these were free graduate-student lines; consequently, all involved welcomed the opportunity. Such students were required to attend the pre-semester workshop and the semester-long seminar. These additional appointments were necessitated by a decrease in the number of English graduate students, the discontinuance of full-time English department faculty in the Writing Program, and substantial growth in the number of enrolled students (e.g., between spring and fall semesters of 1984, EGC101 courses experienced a 24.5% increase).

From the outset, Peter and Pat, almost unconsciously, shared goals for the program. Though these were regretfully not formally articulated at the time, this is how they appear in retrospect.

- To create a community of teachers (graduate students, part-time faculty, full-time lecturers, tenure-line faculty) held together by their conviction that their work (the teaching of writing to college students) is valuable—in truth, uniquely valuable. Peter and Pat strongly believed this and worked constantly at conveying the message to all of the program’s teachers.

- To create classes that made the work of writing more than an onerous task merely to be gotten through. In Elbow language, a both/and goal: both academic and something beyond academic, to have a component of fun and play and discovery, to create a space where students can say something in which they feel invested in some way. And to do that while helping students understand the place of standard forms, standard language, academic genres and language, and maybe even play with those a bit too. Students were to be encouraged to do personal writing, narrative writing, and journal writing as well as research and academic writing.

- To recognize that no matter how well any teacher did in the program, we all could always do better by talking among ourselves, reflecting on what we and others were doing, and reading theoretical and practical articles and sharing them along with classroom practices. The aims were always to minimize the unhelpful hierarchy of tenured faculty / full-time untenured faculty / part-time faculty / graduate students, and to stress that all voices were equal. To the extent possible within the hierarchy of academia, this effort was fairly successful: Almost all teachers, regardless of title, felt empowered to enter conversations, make suggestions, disagree, and so on.

- To work toward making faculty outside the Writing Program more attuned to the ways they could build on what students took away from their introductory course, and conversely, to be attentive to what these other faculty deemed important for good writing in their own classes. Unfortunately, grammar and punctuation often seemed most important to them. As far as could be determined, outside faculty viewed instruction in writing as solely the responsibility of the English department and as solely a matter for students’ first year. With some rare exceptions, other faculty felt no responsibility for student writing except to note its shortcomings.

- To alter a huge flaw in the program: its means of assessment—both the method of placing students and the method of certifying their competence at the end of the required introductory course(s). These two methods had been exactly the same.

As noted earlier, the proficiency exam was introduced in the 1977-78 academic year. Students who came to campus for their orientation in the summer before classes started spent two hours responding to one of three prompts, using the ominous blue book. A committee, composed mainly of graduate students (who were teaching in the program or who had taught in the program and who were paid an extra stipend), read and placed the students: most in EGC101, some in ESL, and a few in EGC100. Since these latter two courses were limited to 15 students each and usually there were four sections per semester, only about 120 students were placed into them annually. The authors can only wonder if such a system now exists in any university anywhere: graduate students placing students in writing classes. Furthermore, any entering student who “passed” the test at orientation, a small number usually, were considered to have satisfied the University’s writing requirement—before even being a student. These students were not required to take a writing class—though many did take EGL202, the advanced-writing class.

Students spent the two hours of placement testing in a large lecture hall in the Javits Center, a stone-like building that, to this day, is reminiscent of a tomb. Pat remembers when she was in charge that first year and suggested to the assembled students that they scribble some notes for themselves that they could cross out or rip out of the book before they started on the actual essay and that they save at least ten minutes at the end of the session to look back over what they had written. It was agony even watching them write. Some students finished in a bit over a half hour—ironically, most of them “passed” or were assigned to our one required course. Those who stayed to the bitter end of the testing period, struggling it seemed over every mark on the page, usually performed poorly and seemed to know they had done poorly.

Once the students had passed EGC101 (the required course), they still had to take the proficiency exam again in order to satisfy the requirement established by the University Senate. In other words, it was not the classroom teacher who certified that a student had met the requirement, though teachers assigned grades once exams were passed. Some students were savvy enough to seek help from a writing tutor. Some who still did not pass this barrier had to keep taking it until they did pass—in some cases two or three times. If they failed the exam three times, they could take a special course (EGC103); if they passed that, they were home free on the writing requirement. Ron Overton, one of the original lecturers in the program (now retired), was the person who usually taught EGC103, and both he and the students almost always loved it: they knew they would never again have to take that exam. Furthermore, Ron was free to set his own agenda, and it was well known that this wasn’t even half comprised of academic writing. The course allowed for much more choice of subjects for students, although research and argumentative writing were required. As Ron would acknowledge, the pressure to take “the test” was gone; that freed up some students to find their own voices and come to enjoy that.

Recognizing that the proficiency exam was no way to assess students, Peter and Pat resolved to set up some kind of portfolio system.{6} Meetings to share grading and commenting were already a regular part of the program, but a better way to certify the writing graduation requirement was needed. During the 1984-85 school year, Peter and Pat created an experimental portfolio group, comprised of five teachers, most of them graduate students, who met several times the prior semester to agree on the traits for common portfolio genres. The aim was to achieve some degree of unanimity without rigidity in assigning topics to students and then coming together to score each other’s portfolios on a pass/fail basis. When a discrepancy arose, everyone in the group looked at and discussed the puzzling portfolio. Pat had already had some experience with judging portfolios at the NYU program, which permitted students who failed their proficiency exam to prepare a portfolio with the help of a writing tutor.

Those who participated in this trial run helped to tweak it here and there—a significant community undertaking if there ever was one. But the requirement, because it was a graduation requirement, had to be changed legally, by getting approval from the Faculty Senate. The Senate legislation ended up stating that no student in a required writing course could be certified as competent by just one teacher. That worked well for the Writing Program: competent meant at least a “C” in the required course, and passing meant that some teacher other than the student’s classroom teacher attested to the quality of the portfolio. This was interpreted to mean that a teacher could not pass a student whose portfolio was deemed unacceptable but could fail a student even if the portfolio were deemed acceptable. As is still true today, not passing the required course necessitated a retake but did not affect students’ grade point averages. Furthermore, all those involved in the program change were pleased to have this semi-mandatory reason for sharing student papers and the standards by which teachers assessed them. Unlike so many later changes that have since been changed again, these ones—which are still in effect today in the PWR—originated within the program itself and were tested by the teachers themselves before any outside authorities were asked to accept them. The agreed-upon prescribed contents for the portfolio were: (1) a narrative, (2) an argument, (3) a text analysis, and (4) some form of in-class writing that was not well standardized. The only restriction was that all work had to be done for the class. The entire teaching staff decided on these genres in order to allow for personal or non-academic writing, academic writing, and analytical writing.

To the disappointment of all, Peter left in 1987 to take a position at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Pat succeeded him, and as she and others recall, what followed were good, satisfying years. Procedures remained mostly unchanged in this time, but unfortunately these procedures did still include the use of the proficiency exam for placement. However, Alice Robertson, Pat’s successor as director in 1995, was able to institute a change.{7} This change also originated within the program, but was accepted by the Orientation Office.

During summer orientation, incoming students were assigned to a group no bigger than twenty-five for a “writing class” taught by instructors with at least four semesters of experience teaching in the program. The teachers playacted a classroom, getting students to talk about possible topics, freewrite a bit, share, and talk some more—just as in real classrooms. They then had the remaining forty-five minutes or so to revise this beginning into a formal essay. All their work was collected and assessed by the teachers who had conducted the classes; this system allowed teachers to examine revision efforts as well as a finished essay. Placement was available usually by the end of each orientation day. This process thus became part of the creation of a community since teachers shared student work with one another even before the semester began, and that inevitably evolved into talk of assignments, standards, pedagogy, and so forth. These teachers already had a sense of the level of ability of the incoming class and could carry that into their classrooms. This system was also a move toward creating a tiny bit of community for the students in the classroom—a common goal they could work on together. A program handbook from that era describes the rationale for this “new and different procedure” as including the reduction of “test anxiety” in students, “a chance to relax and think through their ideas before actually composing an essay,” and “hands-on help from a qualified instructor and peer feedback from fellow students” (Robertson and Belanoff 5).{8} The system remained in place for only two years, killed by the Orientation Office, which claimed that students were put off by having to take a test during their orientation. So far as we know, students were not polled about this; anecdotal evidence among the writing faculty suggested that students, in fact, liked the process.

In the early 1990s, four of the part-time teachers (Ron Overton, Frances Zak, Clare Frost, and Carolyn McGrath) successfully fought for full-time status, health benefits, a salary boost, and three-year contracts (see Frost et al., and Schell 111-12). Although the directors of the program supported and encouraged this effort, it was mostly the instructors themselves, with the help of the union, who fought and won the battle. This would pave the way for the addition of more such lectureships later in the decade, under very different institutional circumstances.

A major change

In 1998 Robertson left Stony Brook to become Director of Composition at Western Illinois University, and in that same year, the Writing Program was separated from English, though it was (and is) still housed in the same building. The Writing Program’s tenure-line director now reported directly to the Arts and Sciences Dean with full autonomy and a dedicated budget but initially without any degree-granting authority.

Although Pat had been director or associate director of the program for eleven years while it was part of English, she was never consulted as this change was discussed and implemented by the administration. The Dean’s Office convened a special committee for this purpose, and Pat was not asked to serve on it. The only faculty member from English who did serve on this committee informally approached Pat and admitted to knowing little about the ramifications of the change being made. To this day, the true reasons for the Writing Program’s separation from the English Department remain obscured. In retrospect, Pat concludes that the change resulted from the hiring of a new Writing Program director who was not the English department’s nor the search committee’s first choice, and from the need for a new dean to “do something.”{9} This separation definitively marks the manner in which most decisions about the teaching of writing in the program would be made for the next decade at ever farther remove from those who were doing that teaching. Soon after, the program was renamed the Program in Writing and Rhetoric, a title it holds to the present.

Between 1998 and 2008 the directorship of the PWR would change hands five times, from Kay Losey to Anne Beaufort (interim) to Pat Belanoff (interim) to Kathleen Welch to Pat again (interim again) to Gene Hammond. With the exception of Pat, all of these appointments were external candidates hired by committees formed by the Dean’s Office. Only for the last of these appointments was the chair of the hiring committee a member of the English Department. Occasionally lecturers served on these committees, though their voting power was a chronically contested issue. In this same decade, the number of tenured or tenure-track faculty in the PWR rose from one to three, then shrunk to zero, and then returned to one. A graduate certificate program in composition studies was created but went dormant after a few years. Since then, a very few Stony Brook doctoral students have graduated with concentrations in rhetoric and composition. A 2005 external review concluded that despite its knowledgeable and committed faculty, the PWR had “no firm identity” and was institutionally “vulnerable without a strong, disciplinary home” (McLeod, Holdstein, and Roen 2, 4). Perhaps for this reason (or perhaps not: again, the PWR was denied access to the rationale deciding its fate), the University administration tried and failed in 2006 to rejoin the English department and PWR. The Dean of Arts and Sciences at the time was a chemist who liked to call this mission an “annealment.” Whatever its label, neither of the faculties would accept a recombination; the equation was unbalanced.

Many other changes occurred in the turbulent ‘98-‘08 period, during which the writing faculty did not always feel supported by its programmatic leadership and in which contingent members sometimes possessed no voting rights in decisions affecting their own fate. Teachers felt that they had little say over how the program functioned with regard to standards, genres, portfolio requirements, curriculum, and hiring decisions. Even when PWR faculty served on hiring committees, they were made to feel mainly like appendages. Decisions were often made unilaterally by the PWR administrator(s) and/or by members of other departments who served on such committees, many of whom knew almost nothing about the teaching of writing.

An internal, self-generated document from April 2005 laments a then newly created (and since dissolved) “advisory committee” of cross-disciplinary tenure-line faculty on which PWR lecturer representatives had “no voting privileges,” a move characterized as “a betrayal because it implied that we [PWR lecturers] were not competent and professional enough to influence or shape administrative and other policies that involved us” (2). By this point, two PWR directors had left the University in as many years, committee work and program meetings had become discontinued or uncharacteristically contentious, assessment procedures had been changing radically (see below), and a highly disruptive cycle of regular exiting or firing of office assistants was underway. This 2005 document, titled simply “Morale,” opens as follows:

Morale in the PWR is as one lecturer put it ‘at a very, very low ebb.’ There are feelings of powerlessness, frustration, despair and even doom among members of the full-time faculty, as a result of abrupt and frequent changes in the administration of the program, program policies, and curricular guidelines. These changes have led to a diminished role for lecturers, confusion regarding procedures, and the sense that we can no longer count on the leadership to advocate on our behalf. There is a growing feeling that our vision of the writing program is at odds with that of the [PWR] administration and that our experience and expertise are not valued.” (1)

During this ten year period, the number of full-time lecturers grew to as many as twenty-six while the percentage of them with terminal degrees more than quadrupled; however, a funding scare in 2004 threatened half of this group’s jobs—with no regard to qualification or seniority, only to whose contract term unluckily happened to be up at the time. This prompted considerable faculty turnaround, although the lines were ultimately not lost. Unfortunately, these and other such struggles are not uncommon to writing programs around the country, and they demonstrate some of the implications of contingency on shared governance as well as a lack of respect for those who are off the tenure track.

More and more decisions were being made outside the program or in consultation only with the director. Instructors were rarely asked to contribute suggestions; at times they never knew of the changes until they were actually in or about to take place. Procedures and materials for placement were changed several times with little to no faculty input. As of 1998, hard copy placement essays were still being written at orientation; this was pedagogically somewhat justifiable, as teachers in the program made the decisions, but also most expensive and implemented at the worst time in the administration’s eyes. As of 2003 electronic essays were being composed at students’ homes using MIT’s iMOAT software, which was less pedagogically justifiable, but also less expensive and better timed. As of 2008 SAT scores were being used, which was not at all pedagogically justifiable but also no cost to the University and best timed, since the orientation coordinators could then be relieved of having to schedule any placement testing. Almost every year plans to turn to the SAT were successfully fought against, but eventually the University administration got its wishes on this issue as part of a compromise for more freedom for the PWR in making part-time faculty hiring decisions, which it arguably should have had in the first place.

Just as with placement procedures, outcomes assessment practices were prone to shifting demands of bureaucratic mandates. Not for the last time in its history, the PWR would relinquish, in 2003-05, real-time face-to-face dialogue during the portfolio assessment process. Former SBU Writing Center Director Harry Denny has critiqued the context for this phenomenon:

as the years passed, the value placed on particular elements of the portfolio changed, and the evaluation process became less invested in the conversations happening between faculty about student writing and more attuned to ensuring consistency between those readers. In effect, rich talk between peer instructors gave way [to] sterile reading sessions where conversation came to be viewed as skewing ‘objective’ scoring and as generally biased. (28)

Denny continues, referring to a (since abandoned) statewide edict to conduct “value-added” outcomes assessment in those days:

With the push for assessment hitting SBU at a time of transition between writing program directors and with institutional support uncertain, the strong esprit de corps among lecturers (if not also teaching assistants) had been a constant. The campus-based study should have tapped into that community and married its investment with the state’s needs. The program directors, one of whom I was, might have yielded different results by facilitating the community’s learning curve and having the local protocol rise out of its tradition for thoroughly collaborative work. Instead, the process tended toward a corporate top-down model. . . . Since agency in the assessment project was so tilted toward administrators, the day-to-day practitioners felt out of the loop, de-valued, and eventually withdrew support [for the assessment project], and the results only served to bear out their suspicion that assessment was a trap for them. (43)

The portfolio system, born at Stony Brook and since widely adopted by universities nationally and internationally, thus began to lose what made it most praiseworthy: the sharing of the teaching of writing through looking at and discussing what other teachers think, assign, and teach. The portfolio process had made a community out of the teachers and even among students in many instances. But the larger the program, the stricter the procedures, and the more remote and hurried the dialogue, the less connected through discourse these stakeholders felt to each other.

To the present

Since 2008, the PWR has continued to undergo significant changes, now mostly for the better (details below), while enjoying a renewed cooperative and inclusive relationship with its leadership. We speculate that this improvement is partially (perhaps mainly) rooted in agreement between those in the PWR itself and university administrators who have the last say on the hiring of a new director. Perhaps this agreement permitted administrators to consider it now safe to turn most decisions back to the program and its new director.

The program now offers well over 200 sections to nearly 5,000 undergraduates annually. Tenure lines are up to five, its highest number ever. Full-time lecturers currently total twenty: twelve of them have Ph.D.s (in various subjects but not rhet/comp), one is an M.F.A., and one is ABD. About the same number of part-time lecturers are also employed in a given semester, and more than forty graduate and undergraduate writing center tutors are on staff.{10} Since a 2012 negotiation with a writing-friendly dean, all part-time faculty are paid $5,000 per three-credit course (up from $3,000), which is nearly twice the national average adjunct wage across all postsecondary institution types (Coalition 2). Part-time faculty receive formal and informal mentoring from full-timers, take active part in all program activities, and consistently demonstrate great capability and dedication as teachers. Current full-time lecturers have held their positions on average for about a dozen years. As for coming up through the ranks, one of the program’s assistant professors is a former lecturer, exactly half of the lecturers previously held junior in-house positions, and part-time faculty who are interested in remaining in their positions for years almost always are able to do so. The tight-knit current nature of the faculty encourages an atmosphere in which these outcomes are possible and desirable.

In what the authors believe is a grievous loss for English graduate students, the PWR stopped employing graduate teaching assistants (but ABDs can be and are hired as part-time instructors, though without a teaching practicum).{11} Unfortunately, graduate students in English now get minimal guidance in teaching, which develops mainly out of their connections to a faculty member for whom they are acting as a TA and which is dependent on that faculty member’s concern for teaching. Although some of those faculty care about writing pedagogy, we consider it ill-advised in today’s job market for English graduate students to possess little or no experience teaching composition. At the beginning of Peter Elbow’s tenure, graduate students applied to Stony Brook specifically to work with him. However, as the number of admitted students decreased in recent years, the English Department did not give much weight to such applications. Nonetheless, a few such students did arrive and, besides, a number of them who came to study literature have more than dabbled in composition studies additionally; a few even changed paths and wrote dissertations in the field (though the degree is still granted in English). Such dissertations were supervised mainly by Pat before she retired. Along with Hammond and Khost, two English Education faculty with significant backgrounds and continued research in the field, Patty Dunn and Ken Lindblom, have also done this work, including the advisement of Master’s theses.

Today, Stony Brook’s graduate students do have the option to work toward an advanced certificate in the teaching of writing, but only a small number of the English doctoral students pursue this option. Having lain dormant for several years, this program has been revived and is doing fairly well, enrolling mainly Master’s students and local high school teachers. The certificate is now in Teaching Writing as opposed to Composition Studies, as it originally was, even though the curriculum has not changed much since revising its name. Recently, Khost and some colleagues have gradually begun to work on a proposal for generating a doctorate-granting program fully or partially run through the PWR—a move that is also part of a campaign to eventually seek full departmental status for the Writing Program.

SAT scores still determine undergraduate placement, even though this practice has been soundly criticized by scholars (most famously, Les Perelman). Thresholds very occasionally undergo adjustments, and entrance essays are used in a small number of cases, especially for international students. Every one of the thousands of exit portfolios submitted each year in the required course is now electronic. On the positive side, this has helped to win the PWR new, grant-funded computing hardware; to motivate more e-portfolio usage across campus; and to nudge students’ academic writing toward multimodality. On the negative side, this means that gone again are the days of writing faculty sitting in rooms together openly sharing and discussing portfolios—other than in optional eighty-minute norming sessions four times per year. Teachers now read each other’s portfolios online, without reference to specific assignments, and communicate about them, if at all, only in the form of explanatory comments for non-passing portfolios. These are usually notes of only a few words—a remote, asynchronous shorthand that pales in comparison with the high quality of the face-to-face discourse and debate over portfolios which was, of course, much more time consuming and difficult to administer.

Attendance at faculty meetings—both official on campus and social off campus—is at its highest point in over a decade, and a “Brown Bag” professional development workshop and presentation series has been thriving. The same is true for a new writing program blog with frequent input from PWR faculty of all kinds, a longitudinal self-motivated self study, and a new invited-authors reading series. The instructors themselves arrange almost all of these activities. In a spring 2012 turn of events that would have been unimaginable at any prior point in this forty-year history, the PWR Director, Gene Hammond, served as both director of the PWR and chair of the fully separate English department for two academic years. This highly unique phenomenon brought attention and increased status to the PWR in the eyes of the University administration. But it also divided the Director’s time, an issue he proactively addressed by appointing seasoned lecturers to the Associate Director and Writing Center Director positions in exchange for a course release and stipend. An engaged faculty has also stepped up to take leadership roles on various programmatic and university committees. Clearly, the PWR no longer seeks just to survive, as it had struggled to do for some time; it now actively, democratically seeks to grow its significance and influence on campus.

Today, with a clear sense of purpose, considerable talent, and tight-knit and constant faculty, it would be neither difficult nor inaccurate to attribute the PWR’s major challenges to external forces: insufficient salaries and resources, impending universal transfer policies, and potential threats of massive scale instructional technologies. After all, as a still relatively low-status teaching-oriented program at a large (intermittently cash-strapped) RU/VH public university, the Stony Brook PWR has tended (until very recently in some cases) to lack the respect, funding, and understanding that we feel we deserve from administrators and other disciplines. But our effort to gain improved attention nevertheless begins at home, and as has been shown, things are improving. If we do not advocate for our own causes, then no one else will, and the same goes for the field of composition studies in general.

Thankfully we now have a basis from which to grow these efforts, including a well-documented, foundational program history, complete with major figures and accomplishments; a growing sense of intra- and inter-disciplinary initiative; and a number of collaborative projects in action to improve the program’s performance and status. This collaboration has often taken a self-reflective form, including the coauthoring of a 35,000-word report on an internal study of the PWR’s basic writing instruction on which we are “closing the loop,” an ongoing self-study of the new upper-division curriculum, and the implementation of a continuous 4-5 year cycle of formative programmatic self-assessment. Mutual consultation has since become a programmatic norm so that, for example, when decisions about emerging online pedagogies had to be made, all members of the program were encouraged to contribute to the discourse, from new part-time faculty to the director. Or as the College of Arts and Sciences now searches for a new dean, the PWR has organized ourselves such that at least two of us are present at every public meeting, asking questions that we collectively generated on our listserv and recording extensive notes in a Google doc shared with our entire faculty. This culture of self-respect and reflection emerges from our reunion conference as an embodiment of the program’s renewed sense of community. That celebration of our history generated by faculty stretching across thirty-plus years—which could not have occurred during the PWR’s period of turmoil—energized current administrators and faculty, instilling pride in all and enhancing the program’s image on campus. It is to this renewal of purpose that we also attribute a number of the changes discussed below.

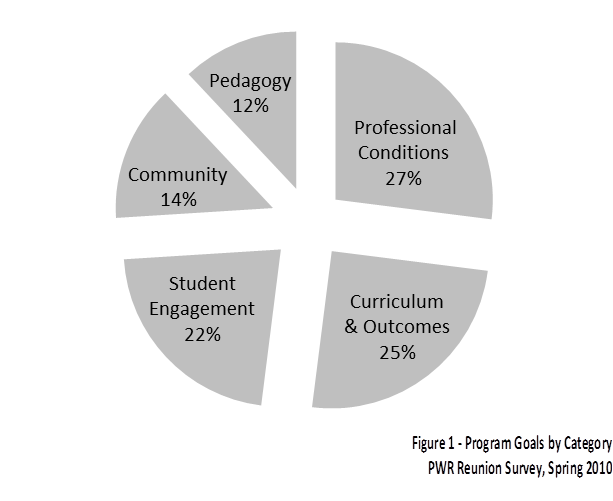

When the current faculty was asked at the reunion conference to anonymously record their opinions about the goals for the program (see the first paragraph of this profile), they provided and ranked insightful responses that have since motivated a number of successful and promising initiatives. This chart indicates the self-generated categories of responses and corresponding percentages of total answers given (see Fig. 1). Recharged with enthusiasm and confidence after the reunion, the faculty decided to address in order of priority the goals indicated by their survey results. Of top concern—comprising 27% of the survey feedback—have been professional conditions including job security, pay, and status on campus. (The other categories and their percentages are curriculum and outcomes at 25%, student engagement at 22%, community at 14%, and pedagogy at 12%.) This may seem less self-serving in light of the fact that at the time of the reunion survey, all but one of the PWR’s faculty were contingent employees, and the lecturers’ contract renewals had recently been downgraded to an annual basis from once every three years.{12} For this, the most notable outcome of the faculty’s survey-inspired decisions, to date, has been to increase advocacy for better contingent employee conditions. This effort has paid off somewhat in the last year, as part-time salaries were increased by 40% and a senior lecturer rank was created, bestowing improvements in professional status, compensation, and presumptive job security on our first cohort of four Provost’s Outstanding Lecturers (in 2012) and second cohort of two (in 2013).

Figure 1. Program Goals by Category—PWR Reunion Survey, Spring 2010

Service and professional development have also spiked in the last few years, with PWR faculty roles and accomplishments including President of the Faculty Senate, Undergraduate Council representative, officer in national and regional associations, learning community co-creator, internship and independent study coordinators, national and international conference presentations, scholarly publications, and teaching abroad sabbaticals (one in Portugal and others potentially in Moscow and Morocco). Although such progress may not be necessarily attributed to a coherent and confident faculty or to the reunion event that brought that community together, it is true that these indisputable signs of a healthy professional culture were quite rare in the PWR prior to 2010. So there’s reason to propose at least some correlation here—lending support to Michelle LaFrance and Melissa Nicolas’s claim that the work of writing professionals cannot be properly understood apart from its institutional contexts (130).

In fall 2010 the PWR developed and submitted to the administration an ambitious five-year strategic plan (see Appendix 1) directly derived from our reunion conference discourse, nearly three quarters of which has been fulfilled in four years (Khost et al). This document promotes in particular the stated goal of expanding our curriculum, and, despite a general state of institutional retrenchment in much of the interim, we have managed to create and offer over twenty distinct, new 200- and 300-level courses in the past few years (see Appendix 2). Only a few years prior to this, literally no undergraduate courses above the 100 level were being offered. This recent curricular momentum led to the first campaign in the program’s independent history for the creation and approval (in fall 2011) of an undergraduate minor concentration in writing. This was the inaugural endeavor undertaken by a curriculum committee revived in that year after its dissolution for six years, a committee that continues to conduct programmatic research and variously includes part-time faculty, full-time lecturers, tenure-stream faculty, and program administrators.

In its first two years of existence, the writing minor has attracted over 100 enrollees almost entirely by word of mouth, and a study concerning transfer and the new writing minor is set to begin soon. A great and unprecedented development to emerge from the new minor is the PWR faculty’s engagement in abiding relationships with undergraduate students. As an improvement affecting literally all of the categories of goals stated in the reunion conference survey (specified above), the minor has improved working and learning conditions in the PWR in part by forming faculty/student relations that last for years rather than only for fifteen or sometimes thirty weeks, as had always been the case before. This includes a burgeoning culture of writing-related independent studies and internships that would have seemed far out of reach prior to our reunion, where the faculty determined to improve the state of the curriculum and student and faculty experiences.

Now with both a stable leadership and a coherent and confident self-image, the program has also recently developed promising new cross-curricular initiatives, including productive alliances with a number of STEM disciplines; several grant awards and more applications in process; the addition of a line for an international T.A.; new teaching opportunities, including composition classes for graduate students in the sciences and abiding connections with the Honors College; publishing collaborations; and inroads toward improving the languishing upper-division writing requirement in disciplines across campus. The PWR’s self-motivated advances in eportfolio usage have attracted national recognition, our writing faculty and students have been featured on the University’s homepage (which was unheard of in prior years), and Khost is running a research study that has paid thousands of dollars to part- and full-time PWR instructors as teacher facilitators.

After professional conditions, the next highest faculty priority that was identified by the reunion survey involves learning outcomes. As demonstrated above, portfolio assessment is one of the oldest distinguishing characteristics of the PWR family history, yet to this day “the portfolio,” as we call it, also remains the most disputed aspect of the program. This consistent and contentious genetic strand in the PWR’s lineage yields a kind of unity without unanimity that can be healthy for a program culture. The requirements of our exit protocol in the required WRT102 course remain largely the same as they have always been, with one notable difference. It has been discussed and decided that the three traditional genres—an argument, an analysis, and a personal narrative—should no longer be conceived of as primarily formalistic determinants but rather in terms of strategies available to writers in a wide variety of rhetorical circumstances. In other words the nouns: argument, analysis, and narrative have given way to the verbs: argue, analyze, and narrate. So the present-day portfolio still requires argumentative and analytical writing, but this work is not limited to any particular genre. Narrative remains fairly popular pedagogically but has become optional for the portfolio, as the general view of the required course has drifted more toward a particular view of “academic writing.” (Pat believes the non-requirement of narrative is a gross mistake; Khost employs it minimally in WRT102 but significantly includes narrative in his upper-division writing courses). The portfolio now also requires a multiple-source research element. Although the quality of that work varies widely across the 100+ sections of WRT102 offered each semester, faculty discussions have begun to raise expectations and improve performance in this regard.

However one may regard these changes, they are admirable in that they grew directly out of the program itself—conceived, debated, and implemented by the teachers in the program, not by those outside of it. We are certain that the sense of shared purpose arising out of our reunion conference’s collaborative self-reflection has been instrumental in dignifying our faculty and encouraging them to become a part of all the workings of the program.

Coming to terms, or: what we’ve learned

Our involvement and that of the teachers in the program has solidified the authors’ bedrock stance: Writing programs function far better for all (students, teachers, and administrators) when those in charge of major decisions rely on input from those within the program and when those who direct the programs conceive of teachers as equals in these decisions. As we have seen, when these factors decay a program can flounder. If we were to create a new writing program today, shared governance, reflectiveness, and self-determination would be central tenets of our professional philosophy.

As hardworking and busy as writing faculties are, they must endeavor to continually develop their programs and to do so democratically if the field is to make further progress toward not only disciplinary independence but also professional parity among its constituency. These internal struggles coincide with external pressures such as a corporate-driven educational reform movement, which as Linda Adler-Kassner notes, is “larger, more powerful, and better funded than any writing teachers, or even any group of writing teachers, will ever be” (The Companies We Keep 136). We encourage compositionists to regard professional advocacy as an additional component to the usual profile of faculty duties: teaching, service, and scholarship—a notion that aligns with Donna Strickland’s call for “a more vigorous materiality” that brings “attention to writing programs as the workplace of composition” (7, emphasis added). These days a number of publications, presentations, and organizations seek to resist the increased corporatization of higher education and national threats to collective bargaining, and their vital activity must not cease. However, such endeavors remain distantly extracurricular to the day-to-day work of many compositionists, whose overwhelming teaching loads and constant struggles to get or keep their tenuous contingent jobs leave them little time and agency to undertake activism or self-reflective scholarship.

But the latent majority of compositionists still possess some power to generate influential solidarity through local, organic, and proactive—not just reactive—measures. Although teaching, service, professional development, and even most scholarship do not commonly register as forms of collective action, this work can be performed and represented in such ways as to build community bonds and to change the ways compositionists and others think about the profession, as Adler-Kassner inspires in The Activist WPA: that is, if it is reflected upon and historicized as communal activity organized around mutual values. Etymologically, the term community suggests a state of sharing common duties; therefore, in the present context we can take the word to subsume at least (1) the day-to-day tasks all writing teachers regularly practice, (2) the goals and standards they share as a discipline, and (3) the legacy they inherit and pass on, both locally and generally—all of which potentially lend compositionists a source of unity on which to draw. Similar reasoning has motivated such major efforts and accomplishments as the founding of NCTE; the Wyoming Resolution; the English Coalition Conference; the Portland Resolution; the WPA Outcomes Statement; the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing; and various recent movements, forums, and publications addressing contingent labor inequities. But the field and its local sites must become much better at reflecting and drawing on our collective sources of strength in order to more effectively confront the challenges that writing educators still face every day.

Those of us who advocate on our own campuses as well as in the larger national scene know how extremely difficult it is to achieve significant reform on either stage, especially the latter. Not to disparage such vital aspects of our field’s culture, but neither recommendations issued by professional organizations such as the CCCC, NCTE, and MLA nor the awareness raised by well-intended publications will result in much change on their own.{13} For effective action to follow these important first steps we must assert local and material iterations of the values they promote. For example, writing faculty must (continue to) band together nationally to ensure that often-autocratic administrative partnerships with corporations and/or experiments with technology do not hinder our ability to provide high quality writing instruction. At the time of the writing of this profile, a very well researched petition against the emerging issue of machine scoring of student writing had gathered over 4,000 signatures and received some attention in public news media (see humanreaders.org), but efforts to effectively adapt pedagogy to such technological developments also require support at regional and local coalition levels, where rubber meets road—perhaps especially at public institutions.{14}

For instance, in the summer of 2013 when SUNY writing faculty faced an external challenge to the shaping of composition instruction—in the form of potentially hasty administrative decisions about MOOCs—some of the PWR faculty collaborated with the SUNY Council on Writing (CoW) to compose a petition that gathered well over 400 signatures in a short span of time (SUNY CoW). This petition and a related resolution reasserted the importance of shared governance while also expressing openness to exploring the benefits of recent technological developments, including MOOCs. The idea is certainly not to resist change but to keep control of writing-based educational developments as much as possible in the hands of expert writing educators, themselves. Participation in local campaigns such as this one can help to generate more, and more widespread, advocacy. Indeed, one of the PWR members who was active in the SUNY CoW project is now helping to lead a nationwide collaboration between writing teachers and United Opt Out by means of a petition against automated scoring of student writing.

As has been shown above, one natural way to begin collective reflection and identity making is through participation in faculty (re)unions. Another way is through one’s pedagogy. Partly for this reason, one of this article’s co-authors (Khost) has developed for the PWR’s graduate certificate program a course called Literature vs. Composition: Professional and Pedagogical Issues, which closely examines the historical split between English and composition studies nationally (from Harvard 1874 to Writing About Writing) as well as locally at Stony Brook. The other co-author (Belanoff) has provided the course with invaluable insight into these matters as an annual guest lecturer whose histories, stories, and visions perpetuate and expand the PWR’s genealogical lore, and welcome the next generation into the program’s and the field’s emerging senses of community.

The co-authors’ classroom collaboration has also helped to produce this article and the potential for community-building elsewhere that it seeks to inspire. We hope that readers of this piece will (continue to) take active steps to improve their professional circumstances, which means not only banding together with colleagues to advocate for better compensation, but also seeking out deeper, subtler ties that bind and applying them in classrooms, personnel committees, administrative negotiations, contact with publics, and elsewhere. The national trend toward independent writing programs offers composition studies reason to be hopeful, but this vague energy can also evaporate without community-level follow-up that accounts for labor. Ultimately, efforts for improvement must be taken up locally with clear purposes, planning, and persistence. Collective reflection and open discourse are also vital to this progress.

Looking back now on the PWR reunion conference, it seems safe to declare that day one of the most joyful and rewarding collective experiences the program has had in the sixteen years of its independent existence—a period, it would be insincere to deny, that has included considerable turmoil and abiding stratification: a partial inheritance from the conflicted act that bore it. If the PWR has come of age and is now gradually coming to terms with its many difficulties, then this can be attributed largely to the accumulation of a referential history upon which the program’s identity is built and represented. Like a family album, we hold onto photographs of the reunion conference and after party, and like an heirloom, many of our faculty keep copies of A Community of Writers near at hand in our offices or at least in our hearts and minds as we teach. This textbook was used in draft copies for two years and revised by Peter Elbow and Pat based on input from those who assigned it as the main text. A whole new article could probably be written examining the continuing influence of the philosophy behind this text on the program itself.{15}

We look to this text and its values for direction as teachers, out of pride as colleagues, and for a sense of community as a generation in a lineage that long predates and will long outlast our current pedagogical and professional struggles. We look to the progenitors of our program (i.e., Peter and Pat), to those who worked closely with them (e.g., Bruce Bashford, Alice Robertson, and Fran Zak), to the next generation that has left home (e.g., Marcia Dickson, Pat Perry, Valerie Reimers, Paula Tran, Tina Good, Leanne Warshauer, Leon Marcelo, Jessica Yood, Gabriel Brownstein, Harry Denny, Sharon Marshall, Jody Cardinal, and Stephanie Wade), and to each other. We reflect on the resemblances and divergences that enrich the PWR’s family tree, along with its scars and new shoots. And we turn ahead with determination to the seasonal cycle of semesters, hoping to leave the condition of our community better than it was when we came into it.

Shirley Rose encourages compositionists to employ “strategic rhetoric to engage our institutions and communities in effecting change and to reflect on our actions, energized by one another and sustained by hope” (230). You can contribute to this effort by sharing your list of program goals (that we asked you to assemble at the beginning of this profile) with your colleagues and by asking them to reciprocate, eventually joining your unified energies with that of others in cultivating a collaboration among writing teachers with sufficient agency and determination to enact reforms of its own design. An important part of community-building involves the combining of personal, archival, and institutional narratives. Let us never forget that the personal—as well as the personnel—is political.

In concluding, we offer the condensed version of overarching alterations in our program that we have traced as a backdrop for others as they examine both their own departments and the changes occurring within the discipline at large. We see these alterations in our program as movement and progress for writing specialists. Concerning disciplinarity we have evolved as such: from a program fully embedded in an English department to hiring of composition faculty and adjuncts within English departments to a free-standing program aspiring to departmental status; from having little or no say to most of the say in decisions affecting writing; from primarily inward-focused energies to partnerships across the disciplines; from nearly no influence on faculty beyond the program to minor and growing influence; from only first-year and basic writing courses to flourishing upper-division and graduate curricula; from 78 total classes in the 1982 academic year to 230 in 2013; from an exclusive concentration on teaching to a burgeoning investment in research, theory, and service; from relative isolation to the sense of a nationwide affiliation. Concerning professional conditions we have evolved as such: from a staff of literature professors to TAs and adjuncts to part-time lecturers to full-time lecturers and adjuncts to no graduate students to senior lecturers and tenure-line faculty; from being mostly MAs in literature to mostly Ph.D.s in literature, but also other fields (and three in composition); from a two-room cubbyhole for pen and paper student tutoring to a full-fledged writing center with a faculty director, various ranks of graduate and undergraduate tutors, and electronic operations. Concerning pedagogy we have evolved as such: from in-house placement via timed essay to a simulated class producing an essay to iMOAT technology to the SAT; from timed blue book exams to portfolios to electronic portfolios; from narrative/argument-centered portfolios to argument/research-centered portfolios.

The evolution does not stop here, and we seek together to ever grow our influence on the changes and our learning from those changes.{16}

Appendices

Appendix 1: Program in Writing and Rhetoric Strategic Plan, 2010-2015

The Program in Writing and Rhetoric (PWR) seeks foremost to offer Stony Brook University (SBU) students the highest-quality writing and rhetoric instruction. The PWR faculty is very well qualified and eager to expand the scope of its excellent work. Achievement of these goals is contingent upon the SBU administration undertaking a number of professional and curricular steps that will support SBU students in their undergraduate and graduate work, as well as in their professional education and employment, and that will empower the PWR to reach its full potential: institutionally, regionally, and nationally. The most significant of these steps are outlined below.

The PWR Strategic Plan Committee compiled the following five-year plan outline based on input from the following sources: (1) an anonymous live survey of full-time faculty on 5 March 2010, (2) a Program meeting on 1 September 2010, (3) an anonymous online survey of full-time faculty from 1-15 September 2010, (4) the PWR Self-Study of May 2005, (5) a 15 September 2010 memo from Dr. Gene Hammond, (6) pedagogical, curricular, financial, and labor-related best practices in the field of Rhetoric and Composition undertaken by comparable research institutions, and (7) consultation of the Committee members during September 2010, including: Dr. Peter Khost (chair), Dr. Jennifer Albanese, Ryan Calvey, Dr. Jackie Corrigan, Dr. Cynthia Davidson, Ann Horbey, Dr. Robert Kaplan, Dr. Rita Nezami, and Barrie Stevens.

Changes in Professional Conditions

[Dots indicate completion of the corresponding objective.]

- Salary increases, to be competitive with comparable institutions, regionally equitable, and commensurate with experience

- More professional development resources, including better travel funding, and research and publishing support

-

Instituting the senior lectureship for lecturers who qualify, including, in addition to 1-2 above (and with reference to the guidelines endorsed by the Arts & Sciences Senate Executive Committee and adopted by the Arts & Sciences Senate on 23 March 2009):

- Improved job stability (promoting academic freedom, longer contracts, better respect among colleagues of superior rank)

-

(Partial) Improved reappointment procedures (easing their frequency and

burden)

Leave time for professional development

- Restoring the unfilled tenure-track positions of associate director and writing center director (lines restored, but not in such positions)

- Creating new tenure-track positions, such as a digital media director (new line, but not in this role)

- Returning to at least 26 full-time lecturers

- Minimum salary for part-time teachers of $5,000 per course

- (Partial) Business cards for those who want them

Changes at the Undergraduate Level

-

Establishing a writing minor, including:

- Expansion of WRT301 courses (Advanced Disciplinary Writing) such as Technical Writing, Business Writing, Legal Writing, Writing about Sociology or Writing about Music, as requested by other departments

- Expansion of WRT302 courses (Writing in the Humanities) for further upper-level writing practice, such as Writing and Theory

- Expansion of WRT303 courses (The Personal Essay), currently serving a percentage of the Pre-Health student community

- Expansion of WRT200 courses (Grammar) for students with weakness or particular interest in this area

- New courses with particular emphasis on rhetoric, including non-traditional rhetoric, new media, and semiotics

- New creative writing courses (all genres, including creative nonfiction)

- Cross-listing of courses as need be

-

Increased purview of PWR instruction across campus, including:

- (Partial) Expansion of the roles and requirements for undergraduate writing instruction in the upper division, writing across the disciplines, the first-year experience (learning communities), etc.

- Influence on the standards for, and on the assessment of, the upper level writing requirement in every department in the University

-

Writing-intensive courses in every major, renewing emphasis on critical and creative

thinking through composition

- Improved arrangements for Non-Native English Speakers (NNS)

- Continued improvement of writing assessment procedures

- Expanded usage of e-portfolios

- Better advertisement of courses and themes

Changes at the Graduate Level

-

Developing the Graduate Certificate Program in Composition Studies, including:

- Significantly increasing the number of enrolled students through greater awareness and better advertisement of composition/rhetoric’s favorable status in today’s difficult job market

- Interdisciplinary opportunities, such as courses in writing and grammar for graduate students across the University

- Further involving TAs in this program

Changes in Resources

- More SINC sites for the PWR (reasonably accessible). Alternatively, carts of notebook computers

- (Partial) Expanding the Writing Center, including more specialized and intense tutoring for NNS students, and better outreach across campus

- Expanding our distance learning options (just getting underway)

- (Partial) Improving/developing library skills instruction

-

(Partial) Developing service learning opportunities

Funding for appropriately educational local field trips

Changes in Community

- Better communication with departments across campus, including interdisciplinary faculty development and discourse on writing

- Better communication with administrative offices, including academic advising

-

Providing editorial review for faculty across campus (e.g., on grants and articles) and students writing dissertations

Creating bridge programs to high school and middle school efforts on Long Island -

(Partial) Hosting more scholarly conferences, seminars, and guest speaker occasions

Participating in any existing or potential across-the-disciplines communications initiatives

Appendix 2: New PWR Upper-Division Courses

WRT 200—Grammar and Style for Writers

WRT 205—Writing About Global Literature

WRT 206—Writing About African-American Literature

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Women Writing

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Writing for the Social Sciences

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Writing for the New Media

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Writing About Film/Rhetorical Issues in Film

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Environmental Writing

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Life Writing and Story Telling

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Fiction Writing

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Faith, Literature, and Writing

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: African-American Rhetoric

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Rhetoric of Mental Health

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Rhetorics of Love and Compassion

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Rhetorics of the Hero

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: Worlds Within Worlds

WRT 302—Critical Writing Seminar: International Literature

WRT 303—The Personal Essay

WRT 304—Writing for Your Profession

WRT 305—Writing for the Health Sciences

WRT 380—Advanced Research Writing

WRT 382—Advanced Analytic and Argumentative Writing (*redesigned and reintroduced)

WRT 392—Theory and Methods of Mentoring Writers

WRT 487—Independent Project

WRT 488—Writing Internship

Notes

- Khost has been Associate Director and Writing Center Director; Belanoff has been Director and Associate Director. (Return to text.)

- We encourage readers to participate in the Writing Studies Tree project, which takes this analogy quite literally: http://writingstudiestree.org/. (Return to text.)

- Peter presented Vulgar Eloquence: What Speaking Has That Writing Needs, material destined for his new book (Vernacular Eloquence: What Speech Can Bring to Writing, published by Oxford UP). Pat presented What’s the Past Got to Do with Today? offering insights about writing instruction past, present, and future. (Return to text.)

- Peter Elbow, of course, but also David Bartholomae, Chuck Bazerman, Don Daiker, Lisa Ede, Lester Faigley, Linda Flower, Toby Fulwiler, Doug Hesse, Erika Lindemann, Ed White, Art Young, and many others. See Bizzaro for more on this. (Return to text.)

- Interestingly again, in 2013 Khost (initially contingent and eventually tenure-track in the writing program) officially became an affiliated member of the SBU English department—teaching cross-listed graduate courses, advising English Master’s theses, and sitting on English doctoral students’ dissertation committees. (Return to text.)

- For more information on the history of this portfolio creation, see Belanoff and Elbow and Elbow and Belanoff, “Portfolios.” (Return to text.)

- She has written a description of this innovative procedure in Teach, Not Test. (Return to text.)

- As shall be seen later in the profile, these various opportunities have now all been lost by changes to the placement procedure. (Return to text.)

- For an account of the troubling effect of this change on TAs and graduate students at the time, see Yood. (Return to text.)

- The Writing Center, in one form or another, has been a part of the Writing Program/PWR since its early days. (Return to text.)

- For years, the PWR faculty included dozens of practicum-trained TAs from graduate programs in English as well as comparative literature, cultural studies, theater, music, history, and other departments. The elimination of TAs from the program was driven by a mix of financial, pedagogical, and other reasons, as well as by the English department’s dramatic curtailment of new Ph.D. students over the past few years. (Return to text.)