Composition Forum 33, Spring 2016

http://compositionforum.com/issue/33/

Equal Opportunity Programming and Optimistic Program Assessment: First-Year Writing Program Design and Assessment at John Jay College of Criminal Justice

Abstract: As Brian Huot and Ellen E. Schendel assert, when assessment has more than validation in mind, it “can become a means for proactive change” (208). In response to this idea of assessment as an optimistic and opportunistic enterprise, this article describes how the structural design of our “equal opportunity” writing program and our faculty-led assessment process work symbiotically to sustain, enhance and “revision” the curriculum and pedagogy of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY, first-year writing program. Our writing program strives to offer all students at the college a consistent and equivalent writing experience, regardless of what semester or in what section they enroll, as well as a coherent trajectory, where students encounter similar learning processes and literacy tasks throughout the course sequence. To ensure this consistency and coherence, our programmatic stakeholders designed program assessment to have direct impact on classroom learning by following multiple formative and summative assessments in an inquiry-based practice driven by local curricular contexts. In profiling the quid pro quo between writing program design and its accompanying assessment efforts, we demonstrate how program structure enables useful, progressive assessment, and, conversely, how assessment continuously informs and improves the infrastructures of pedagogy and curriculum in the writing classroom.

Not an optimism that relies on positive thinking as an explanatory engine for social order, nor one that insists upon the bright side at all costs; rather this is a little ray of sunshine that produces shade and light in equal measure and knows that the meaning of one always depends upon the meaning of the other

— Judith Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, (5).

In Unlearning, Judith Halberstam addresses the current crisis in the humanities, namely, “recent trends in universities away from language, literature, and learning and toward business, consumer practices, and industry” (9). After offering this familiar critique in detail, Halberstam advocates for an alternative type of optimism, one that does not present the most evident problems as a means to sustain a status quo, nor one that wears rose-tinted glasses to present a flawless portrait of successful change. Instead, she offers a view that judiciously scrutinizes difficulties with measured skepticism, without allowing it to extinguish a certain sense of optimism and possibility. In doing so, Halberstam does not stop at the familiar tact of expertly demonstrating an educational crisis but, instead, provides the gut check for the bumpy road to solutions. She offers the sound advice to learn to unlearn—“learning, in other words, how to break with some disciplinary legacies, learning to reform and reshape others, and unlearning the many constraints that sometimes get in the way of our best efforts to reinvent our fields, our purposes, and our mission” (10). To support her idea of unlearning, Halberstam quotes Cathy Davidson who states, “Unlearning is required when… your circumstances in that world have changed so completely that your old habits now hold you back” (19). Both scholars bring their skeptical views to bear upon contemporary educational life, but they also offer optimistically divergent propositions to potentially resolve them, emphasizing that change occurs by moving beyond critique and complaint, moving beyond reactionary and limited responses, and moving beyond our secure and typical habits of mind to envision useful and progressive solutions.

We suggest that Halberstam’s skeptical optimism serves writing program administrators (WPAs) particularly well, since WPAs act as university change-agents who often contend with problems at the classroom, program, and political levels that seem intractable because they are tangled in inadequate and antiquated bureaucratic systems and/or long-entrenched programmatic deficiencies. Without healthy measures of both optimism and skepticism, WPAs would not have the wherewithal to see beyond the everyday demands of programmatic administration, curriculum development, and program assessment, in order to look forward to progressive change, innovation and sustainability.

In this writing program profile of John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY, we describe the processes and dynamics of our new curriculum design and its symbiotic relationship to assessment practices as a means to explain our continued optimism, despite the slow pace of change, despite some faculty colleagues who doubt our successes, despite upper-level administrators who demand increasingly more reporting (and “proof”) from program directors (with less funding), and despite external evaluators whose accrediting processes often demand assessments that could adversely influence the internal workings of a writing program. By linking faculty-led program assessment to classroom practice, we are able to sidestep the “burden of proof mentality” that we often face at our urban, public college’s writing program.

Responding to Assessment Demands

Five years ago, when John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s administration began sending out copious, directive emails about the fast approaching Middle States accreditation review, the same-old faculty moan-and-groan could be heard up-and-down the hallways of the English department. In this era of hyper-managed outcomes assessment and amid the waves of public rhetoric about educational failure and a student literacy crisis, administrative missives warning of the need to define and validate successful programs and practices felt equivalently mundane, tiresome, and ominous. Faculty, especially writing faculty, felt fatigued by assessment because we live in a world where, with increasing frequency, we are called upon to respond to a newly emerging group of interloping “estrange-agents” whose interventions often arouse hostility or indifference as they call to upend theoretically grounded and pedagogically sound programs and curriculum in order to reinstate “the standards” or to inscribe the latest educational fad as an alternative.

In our case, the onset of Middle States review coincided with our centralized university (City University of New York) imposition of a new general education model, called CUNY Pathways, which required the standardization of a core curriculum equivalency, including composition courses, across all eighteen undergraduate campuses. Facing these dual interloping “estrange agents,” who did not understand our discipline, our context, or our curriculum, we made it our goal to take charge of the process of program assessment and provide the data for accreditation review and general education conformity on our terms, with our discipline’s best practices in mind, and with our program’s institutional, student, and writing context front-and-center. Despite our administrative weariness and unrewarding past experiences with enforced, whole-scale assessment, we knew we had to exert some autonomy and agency in these latest (but not final) program evaluation inspections. While we were skeptical of the demands of outside intervention, we were hopeful that we could develop our own assessment plan and optimistic that if we as a faculty invested in the process we could not only satisfy our questioners, but successfully create a feedback process to enhance and improve our new curriculum and directly impact classroom learning.

Though the accreditation process and general education standardization may have acted as a catalyst, we had strong reasons for developing an ongoing, program assessment of our own. In 2006, we had implemented an entirely new curriculum for first-year writing: in a three-semester sequence, the new portfolio-based curriculum introduces students to source-based academic inquiry through a series of scaffolded assignments, emphasizes rhetorical context as these impact reading and writing in a variety of genres and disciplines, and pushes student writers toward self-efficacy through a strong reflective writing component. While pleased with our new curriculum as a theoretical model that followed the best practices and insights from our discipline, and while we had plenty of student and teacher anecdotal evidence that the new curriculum was a dramatic improvement from its predecessor, we did not have the assessment tools and processes in place to fully validate our curriculum, which, because of its non-traditional approach, often came under some unfounded (in our opinion) criticisms. We had collected and analyzed data in each semester since the new curriculum had begun, but we knew we had not looked closely enough or with enough consistency to actually use the data to convince external reviewers and naysayers at our own college. But, more importantly to us, we wanted a thorough nuanced portrayal of the new curriculum based on assessment inputs from all stakeholders (students, faculty, and administrators) with the idea that there were some things that were not working and others we could do better. With our own programmatic improvements in mind, this assessment would differ from those carried out in the past because we wanted to do more than validate existing practices: we wanted to continually revise them. In “A Working Methodology of Assessment for Writing Program Administrators,” Brian Huot and Ellen E. Schendel state:

As assessment and program administrators, we look outward toward our curricula, our

teachers, our students, and their writing. Validation supplies us with a way to turn our gaze inward toward the assessments themselves, the program guidelines, and other policies and procedures that after a while just seem normal—“just the way we do things around here.” Looking inward furnishes us with reflective pause that allows us the space to become reflective practitioners. Examining our assessments and their results with a critical eye to consider the possible alternatives for doing things and finding explanations for the results we think we have achieved gives us the opportunity to see our programs and our assessments in new ways. (224)

Conducting this assessment would fulfill the needs of the institution to validate our program to Middle States evaluators, but it would—even more importantly—give us the confidence to forge ahead with revisionary improvements and innovations. When assessment has more than validation in mind, it “can become a means for proactive change” (Huot and Schendel 208).

Throughout the description of the development and implementation of our program assessment process, we underscore the idea that the confluence between instituted programmatic curriculum and assessment enterprises must inform and reinforce each other and, like the writing process we teach our students, the program assessment process must be recursive, inquiry-based, introspective, and self-perpetuating. After detailing our programmatic curriculum design as well as the stages of the assessment processes we undertook, we look at a few specific examples of assessments that have impacted the teaching and learning in our classrooms.

Local Context: John Jay’s First-Year Writing Program

Founded in 1964, John Jay College of Criminal Justice was initially conceived to develop a more educated and humane police force during that socially divisive era. In Educating for Justice, the college’s historian Gerald Markowitz describes the struggles of starting such a social experiment:

In normal times colleges have ten to fifteen years to work out major problems and changes in mission and curriculum. But a public urban college never had that luxury. It began to struggle with the problem of educating the police, and then, only five years later, it was told to prepare for Open Admissions. It began to work out the problems of educating students who had been denied an adequate high school education when suddenly the school was threatened with dissolution.… While the college has had a short life, it has had a long history of dealing with important questions and working out approaches to difficult social and curricular issues. (189)

Even after 50 years the college still focuses its work on resolving these socio-educational-justice issues. Over the past three decades, the college’s mission has evolved, moving away from a focus on police and fire science and narrow vocationalism, and concentrating more on criminal justice broadly conceived, to include majors in criminology, international criminal justice, and culture and deviance. In addition, students can now pursue professional degrees in forensic psychology, forensic science, and pre-law. Over the past decade, the college has broadened its liberal arts mission to include majors in humanities and justice, history, literature, and philosophy. Thus, as we set out to launch a new writing curriculum in 2006, these disciplinary evolutions needed to be considered and “designed into” the learning objectives and course requirements.

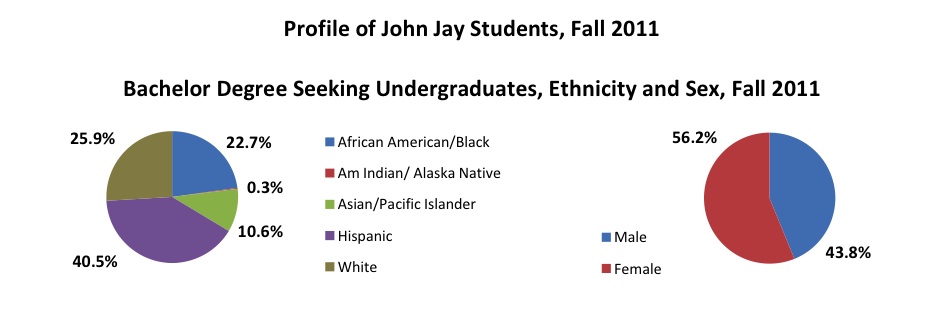

Similarly, the profile of the student body had also changed over its 50-year existence. Located just south of Lincoln Center on Ninth Avenue and just west of Columbus Circle on 59th Street, John Jay sits centrally on the western edge of Manhattan. The college currently has an enrollment of over 15,000 full- and part-time students of diverse ethnic backgrounds (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. John Jay’s Institutional Research Chart.

Though the majority of undergraduates (approximately 75%) reside in one of the five boroughs of New York City, increasingly the rest commute from the tri-state area (New Jersey, Connecticut, Long Island, and upstate New York). Many of the students are first-generation college attendees, many are caregivers/financial providers for their families, and many are struggling with issues related to poverty. As a result, a vast majority of them hold part- or full-time employment. The 2009 National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) showed some key findings about students at John Jay (in comparison with students at peer institutions):

- John Jay College students show patterns of time use similar to those of students at its CUNY Peers, but generally spend more time working, commuting, and caring for dependents than do students at its National Peers.

- John Jay College first-year students show a significantly higher benchmark score for Level of Academic Challenge than do first-year respondents at either its CUNY or National Peers.

-

John Jay College seniors show lower engagement in Active and Collaborative Learning and Enriching Educational Experiences than do seniors at its National Peers.

(2009 National Survey of Student Engagement Benchmark Data, 1)

On average, each week John Jay students work 21 hours, spend six or more hours commuting via public transportation to class, and devote six or more hours caring for dependents. The information provided by both NSSE and our office of institutional research shows the educational idiosyncrasies of our urban commuting student body, extenuating educational factors that need to be taken into account when considering curricular revision.

For its own part the John Jay writing program has had a fairly stable geographic and institutional history. Housed within the English department, the program offers approximately 120 sections of first-year writing courses each academic year. With a course cap of 27 students, the program fills approximately 2,400 classroom seats per semester, with the vast majority taking ENG 101 and ENG 201 in successive semesters. Approximately 30% of program courses are taught by full-time faculty members and 70% by adjunct faculty members. Full time-faculty include five tenured or tenure-track faculty members with degrees in composition and rhetoric or linguistics, and nine lecturers with MAs or MFAs in writing, TESOL, or education. Other tenured and tenure-track faculty in the English department have a long history of teaching writing courses as well. The adjunct faculty is somewhat stable considering the size of the department, with the average term of employment being four years. In total, each semester about 45 faculty members are teaching in the writing program.

The writing program has a director who oversees a composition faculty committee that coordinates assessment, proposes policy decisions, and designs campus-wide literacy initiatives. While the composition committee remains in charge of decision-making for the writing course, the English department (and sometimes the college curriculum committee and college council) still votes upon any curricular changes. Fortunately, the English department has provided a supportive environment in which the writing program has been able to evolve. For example, the past four chairs of the department have advocated for the increasing development of the writing program, and the department as a whole has stood behind the decisions of the composition curriculum committee. In addition, the upper-administration of the college has equally supported the writing program with the hiring of tenure-track lines and full-time lecturer lines as well as offering an increased amount of faculty release time for writing program administration. While for most WPAs and their faculty this educational context might sound idyllic, its achievements came slowly through careful navigations through the bureaucratic labyrinth of a large urban public institution, requiring written proposals, lobbying for funding, and a great deal of patience. Even with these advances our writing course enrollment cap (27) is well above the national average, and our faculty reassigned time for WPA work is below our CUNY peer institutions.

Equal Opportunity: The John Jay First-Year Writing Curriculum

Since the college itself had gone through an evolution from vocationally centered programs to professionally guided liberal arts programs, the writing faculty strongly believed that the curricular focus of the course sequence needed to meet the rhetorical and composing needs of students who face a wide variety of cross-disciplinary texts and contexts in their studies. This belief was supported by a students’ needs assessment of writing at the college conducted in 2002, which revealed that John Jay students might pursue a forensic science course in which they would write lab experiments, a criminology course in which they would do ethnographies, a history course where they would work with primary documents, a police science course in which they would write incident reports, or a law and literature course in which they do critical literature reviews. Moving from department to department, course to course, and professor to professor, students would need to invent and re-invent their situational knowledge of university writing to have an expanded sense of audience, greater rhetorical flexibility, and a heightened awareness of evidential values in differing disciplines. As Lee Ann Carroll warns in Rehearsing New Roles, “The composition establishment tends to view writing through the wrong end of the telescope, focusing on forms of writing appropriate to first-year composition courses [and subsequent English Studies literature courses] but often mistaking these forms for academic writing in general” (5). This was certainly the case in our own English department. In establishing a new curriculum and sustaining a writing culture on our campus, we decided to turn the telescope around.

In response to this complex matrix of disciplinary variety and institutional mission, beginning in 2002, the WPA and writing faculty undertook a complete revision of its first-year writing course sequence, replacing a 30-year-old traditional composition sequence that was based in a belletristic essay/writing for literature model. After conducting research of the best practices in the field (particularly the WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition and the Frameworks for Success in Postsecondary Writing), we designed a portfolio-driven, student inquiry based, rhetorically focused, and discipline-specific writing program which asks students to complete a sequence of writing assignments for diverse audiences in diverse contexts.{1} The new three-course sequence was proposed in 2004, faced curriculum college governance in 2005, and launched officially in 2006. Attending to multi-disciplinary needs of this extremely diverse student body, the new curriculum provides a course sequence that

- serves a writing community largely comprised of English-as-second-language and English-as-second-dialect students who need extended periods of instruction and practice to master reading and writing skills;

- addresses the writing needs of a predominantly sociologically and scientifically oriented (mission-related) curriculum, while still providing the rhetorical sensibilities for a well-rounded liberal arts undergraduate;

- approaches writing as a means of analytical and organizational thinking rather than mere reporting of information;

- presents writing as a scaffolded sequence of manageable, interrelated tasks;

- integrates college resources (i.e., center for English language support, writing center, and the library) into the curriculum to reinforce the activities that occur in the writing classroom;

- emphasizes (and consistently reinforces) the habits, techniques, and strategies necessary to compose a college-level piece of writing; and

- introduces students to the cross-disciplinary aspects of writing, which teaches them how to apply their writing skills in a variety of academic and rhetorical writing contexts.

The research-based curriculum offered a stark alternative to the previous curriculum that had taught students expository writing that focused on literature-based topics and had assigned these essays as disconnected final products. The new curriculum focuses on writing as a process and set of strategies that give students divergent opportunities: to work in a variety of disciplinary genres; to emphasize meta-cognitive learning; to treat rhetoric as the content of the courses; and to increase revision as a practice completed over the semester, not just in short increments.

The Course Sequence

All of the courses in the new curriculum were built to reinforce the same core concepts: developing rhetorical knowledge, focusing on an inquiry-based motive for writing and research, using reflective writing and metacognitive work, and emphasizing writing within a variety of rhetorical contexts, including different disciplines (see Appendix 1). Thus, assignment types and genres repeat throughout the courses, making each course a “rehearsal” for the next course, and the entire sequence acts as a rehearsal for the college writing life beyond the sequence. The three-course series consists of a basic writing course for students who do not pass the university-mandated writing exam, and a two-semester, required sequence of first-year composition (FYC), with the first course as a prerequisite for the second.{2} Most students take the courses in back-to-back semesters.

ENG 100W, the basic writing course, meets for six hours per week and features a series of scaffolded assignments that parallels what students will do in ENG 101, including a research project, while also preparing for the university-mandated writing exam. Students are introduced to the literacy skills, habits, and conventions necessary to succeed at college-level work as they work on a variety of genres of writing (creative non-fiction, annotated bibliography, proposal etc.) while completing both primary and secondary research. While offering students techniques and practices of invention and revision, the course also teaches students the historical and educational aspects of literacy as a scholarly topic.{3} Students “rehearse” the assignments and activities of ENG 101 (comparison, working with sources, composing a research-based essay, writing reflections on their own work, and building a portfolio), and the looming exam is presented as one of the many rhetorical contexts and genres that the students need to succeed at. The class is taught by two different faculty members, thus enabling plenty of individual feedback and time to “rehearse” the university exam writing process as one of the writing contexts and school-genre writing modes that students need to master.{4}

ENG 101 introduces students to the skills, habits, and conventions necessary to prepare inquiry-based research for college. In this theme-based course, students practice techniques of invention and revision while also being introduced to the expectations of college-level research. From a theme that each instructor chooses, students develop their own investigative question and then proceed through a variety of prescribed, scaffolded assignments that jointly culminate into a college-level research project (see Appendix 1). Students collect their best work in a portfolio, which they analyze in a cover letter, and the portfolio (process) work becomes a predominantly weighted part of their final grade. The scaffolding and drafting process built into the curriculum minimizes the often-overwhelming research project assignment, and prepares the students for the research projects that college professors across the curricula value yet rarely present as an interrelated series of analytical strategies and tasks.

ENG 201 exposes students to the preferred genres, rhetorical concepts, specialized terminology, valued evidence, and voice and style of different academic disciplines. Instructors again choose a single theme and provide students with reading and writing assignments that address the differing literacy conventions and processes of diverse disciplinary scholars. Through exposure to research and writing in a variety of disciplines, students become aware of how writing changes from field to field, and, under their instructor’s guidance, they practice a variety of informal and formal types of writing to raise their rhetorical awareness of disciplinary writing. This course confronts the confusion students often have when they attempt to apply the writing knowledge they gained in their primary college-level composition courses to the many forms and conventions expected of them in other non-English department writing courses.

In various contexts where the new courses demanded justification (i.e., department meetings, curriculum committees, college counsel) we relied on programmatic precedents at other institutions as well as the primary scholarship of our field to win the contentious political battles against well-meaning believers in the status quo and malinformed stakeholders who had no background in current research about how students learn to write. We argued that being challenged to join serious conversations about important academic topics, and given enough time to learn and rehearse their rhetorical capabilities in the college academic environment, these often educationally dispossessed students would gain the discourse knowledge, rhetorical savvy, and (yes) the grammatical skills that the academy expects of students with advanced literacies. In designing a curriculum with prescribed assignments, scaffolded steps, attention to reflective writing, and a focus on rhetoric and writing across the disciplines, we believed we could offer an equal opportunity writing program, where all students enrolling in first-year composition encounter a common composing experience that features shared, explicit learning objectives, distinct assignment parameters, set portfolio requirements and an emphasis on reflective writing and rhetorical knowledge. In the ENG 101 course, for example, rather than assign a required textbook or a mandated syllabus to writing instructors, this course curriculum requires teachers to introduce students to a scaffolded sequence of genre specific literacy tasks that act as incremental steps to a source-based, student-designed research project. Students may not encounter the same readings or discuss the same topics, but they will all produce a portfolio that includes a piece of creative non-fiction, a proposal, an annotated bibliography, an outline, first/second/(sometimes third drafts), an interview, a research project (either traditional, multimodal, or hybrid), and a reflective cover letter. While maintaining individual faculty energy, creativity and innovation, the new curriculum ensures that all students attending the college—no matter which section they enroll in—will acquire an equivalent writing experience as they prepare for the diverse writing experiences of their college writing lives. We are all building houses using a certain set of materials, but each class section maintains its in-house creativity and identity. The equal opportunity, thus, not only has impact upon the students in the courses but also upon the instructors who follow, but also adapt, the curriculum to their own intellectual interests, teaching styles, and classroom practices.

Similarly, in ENG 201, we challenge the students with a shared set of emphasis points: rhetorical analysis and writing in diverse contexts/disciplines (WID/WAC). Though faculty may choose to emphasize different rhetorical theories (ethos/pathos/logos, Toulmin’s argument structure, or Burke’s Pentad), and faculty may choose to have students work in different disciplines (a speech or social science fieldwork, or literary close reading, or a quantitative data analysis), the commonality of having students work to establish the transversing core understandings of audience, purpose and genre provides the structure for an equal opportunity experience for all, while not falling into the trap of “teacher proof” curriculum.

Skeptical Optimism: (Re)volving a Process of Assessment

We present this lengthy description of our course structure and curriculum because it was one key to the success of our program assessment. Our assessment program already had a head start, since our new curriculum was grounded in theory and had curricular parameters within a self-described educational framework. We were not assessing an abstract concept of good writing or good teaching practices, nor were we evaluating an entrenched curriculum that no one had any interest in evolving. We had worked collaboratively to create and initiate the new curriculum and could now work together to find data that supported our clearly stated principles, but we also expected to adjust the curriculum based on what we uncovered in assessment. In Testing In and Testing Out, Edward M. White discusses the need for structure in FYC courses, stating:

I like best of all programs based on a reasonable adaptation of outcome statements for each level of the course, using the WPA Outcomes Statement as a model. In that pattern, the outcomes (and the requisite starting abilities) for students in each of the program’s courses are stated with clarity, while the teachers have substantial freedom in deciding how to reach those outcomes. (136)

Although White’s vision pertained directly to the creation of a student placement exam, his preference correlates to an essential step for all assessment practices, including program assessment. The learning objectives that the teachers fulfill in their classrooms should be the same as the learning objectives used in the assessment. Beyond learning objectives, we realize that the ideology and practice of our curriculum and the ideology and practice of our assessment plan should be one and the same. Thus, our assessment plan has followed an inquiry-based, scaffolded, recursive, and self-generated process. We did not need additional measures placed outside or alongside our curriculum. While the requirement of a portfolio and reflective writing strives to help underprepared students negotiate the unfamiliar territories of academic literacy habits, it also enables a close analysis of primary source evidence contained in the final portfolio that speaks directly to the intentions and outcomes of the writing curriculum. Likewise, the prescribed assignments offer us a common denominator by which to view, discuss, and evaluate student work for both “sufficiencies” and shortcomings directly related to our learning objectives. Unlike the former writing curriculum at John Jay where a free-for-all curriculum did not offer any common object of study on which to conduct assessment, our required portfolios with similar assignments provides an assessment device as a common denominator through which we can directly assess what occurs in the classroom. Our assessment process identifies the inconsistencies or lack of coherence in our program, develops curricular and instructional strategies to mitigate those problems, and disseminates the information to the instructors who can then assist in the endeavor to provide a writing program that promises equal opportunities.

The implementation of the new curriculum was carried out fully when the college hired an additional cohort of composition-rhetoric faculty, consisting of three tenure-track lines and nine lecturers, hired over five years. For the first time in its history, the college had a cadre of full-time faculty with the theoretical background and teaching experience to carry out innovative curriculum and classroom teaching in first-year writing as well as curricular and program assessment and revision on a continual basis. All of the newly hired faculty dove into the work of implementing the new curriculum, designing creative, multiple versions of prescribed assignments, mentoring adjunct faculty, and facilitating faculty workshops on everything from reflective writing to digital portfolios.

However, when it came time to assess the program, the faculty seemed to hesitate. As Brian Huot details in Toward a New Theory of Writing Assessment, faculty knowledge in composition practice may not translate to a willingness to devise assessment practices. Huot suggests two reasons that faculty naturally shy away from assessment. Firstly, assessment of learning is a discipline onto itself that composition faculty feel should be left to the experts in educational measurement. Secondly, large scale assessment has become a massive industry that has made us feel naïve and insecure about our knowledge of technical concepts such as validity or inter-rater reliability. This lack of knowledge makes us question our ability to carry out large scale assessments that meet the seemingly objective standards of what Huot calls positivist assessments, testing mechanisms that claim to measure precise degrees of literacy ability. In addition, Huot argues, composition faculty “have remained skeptical (and rightly so) of assessment practices that do not reflect the values important to an understanding of how people learn to read and write” (160). Having watched the creation and enforcement of poor assessment of student writing ability be misused to determine who attends college, who places into a curriculum, or who passes a course, composition faculty feel that assessment is the enemy they would rather not join.

It is precisely at this point that we rejoin the narrative moment in our program history detailed earlier. Among our faculty, general pessimism about the usefulness and purposes of writing program assessment, and doubts about our own abilities and knowledge, were intensified by the “estrange-agent” demands of the Middle States Review and the university-wide Pathways core curriculum centralization, which created an atmosphere of “let’s get this over with quickly.” Though we understood that the consequence of faculty who are unwilling to do their own assessment cedes this control to potentially less knowledgeable, always quantitatively driven administrators or—in another scenarios—to outside assessors who lack an understanding of the local institutional contexts and learning conditions in which students learn to write, at first we designed a standard summative outcomes assessment (OA) that could produce the quantitative data necessary to respond to outside-program evaluators.

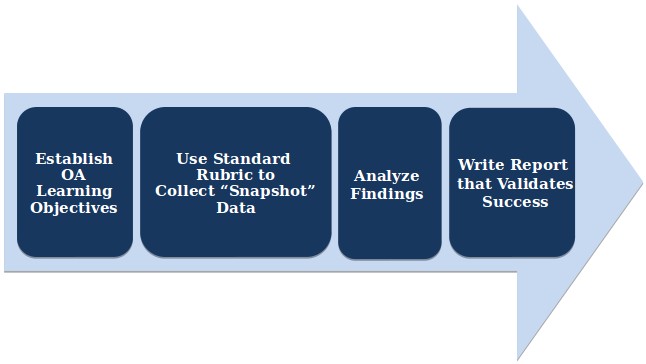

Figure 2 presents the stripped down, standard view of a reactionary OA process, one that is created on demand to defend existing curriculum or practices. Our initial plan followed this standard view: we hoped to create a rubric out of our then existing learning goals (see Appendix 2) and have the faculty evaluate portfolios according to a five-point criteria-based scale in order to produce a set of concrete data that could tell us whether our program was working. Figure 2 looks naïve, simplistic, and ineffectual to us now. When assessment is driven by the need to protect a writing program from outside forces or reaffirm practices for an accreditation review, we tend to think of assessment this way: assessment should be a one-time, linear process that produces almost foregone, reaffirming, quantifiable conclusions that can be used to validate the success of the program.

Figure 2. Standard Outcomes Assessment Process.

If done well, this kind of assessment may validate current practices (good or bad) and produce seemingly sound data to defend the writing program from unwanted or unnecessary changes. Since we were under pressure to do just that, we proceeded.

The inadequacy of our initial plan became clear at our first portfolio assessment session. Sitting down at a long table in our conference room, we handed out a rubric of our learning objectives with a standard five-point scale and began the norming process. Within minutes the side-conversations began. Faculty questioned the wording of the imposed learning objectives, whether the portfolios should be scored based on the course the student was enrolled in or as compared to where they would be when they finished the sequence, and general questions about whether the portfolios contained the right kind of writing to make judgments on things like writing process or reflective writing. The initial sessions ground to a halt and evolved into fascinating discussions of the new curriculum and how well certain aspects were working according to individual teachers. These first sessions produced no quantitative data. What they did produce was a useful formative assessment: a revised set of clearly stated learning objectives (see Appendix 3), plenty of curriculum sharing, and progress toward other assessment methodologies that could be used to balance out the quantitative, rubric-based outcomes assessment data approach we had narrow mindedly though would be the entire assessment.

These initial sessions with teaching faculty led us to understand that our assessment process needed to evolve. We identified these problems with the simple outcomes assessment portfolio review we had designed: the lack of actual engagement with instructional faculty, the one-shot nature and narrow focus of the data collection, the final product-oriented outcomes assessment of the methodology, and the resulting lack of impact on curriculum change. During workshops and planning sessions in the following semester, we debated why we were using this assessment model and how collected data could (adversely) affect us; most importantly, we considered the worthiness of spending the time on the assessment though we knew it would not influence our classrooms. If it would have no impact, why do it? We did not want our OA process to be one of self-justification, where data is collected, reported, and delivered to the department, college, and accreditation agency but never acknowledged as a useful reflective tool for self-improvement. We stopped thinking of the assessment plan as a product-oriented task that produces data to answer a short list of assessment questions and instead focused on a process that would continue to generate questions and, moreover, cultivate methodologies to answer them. Ultimately, we needed to do more than just have our faculty control the assessment: we needed to optimistically (in Halberstam’s sense) rethink how to do assessment to meet our needs and to enhance our program. Like Huot and many others, we realized that our knowledge of the context of our writing program and our understanding of best practices in our discipline was more than enough expertise to overcome any doubts we had about the technical knowledge of assessment.

With the faculty’s initial response percolating, we went back to the research to reaffirm this new direction. As an alternative to our short-sighted data for middle states variety assessment design, Bob Broad suggests more generative questions for assessment:

How do we discover what we really value?

How do we negotiate differences and shifts in what we value?

How do we represent what we have agreed to value? and

What difference do our answers to these questions make? (4)

Admittedly, we happened upon these crucial questions by trial and error, but they eventually made us face our programmatic judgments more carefully and to broaden our ideas of assessment from purely “outcomes-based” quantitative data to more programmatic assessments using a variety of methods and fulfilling a more varied set of faculty-determined goals. As Peggy O’Neill, Cindy Moore, and Brian Huot state in A Guide to College Writing Assessment, “Because writing assessment is fundamentally about supporting current theories of language and learning and improving literacy and instruction, it should involve the same kind of thinking we use everyday as scholars and teachers” (59). We were no longer blindly following the Middle States mandate but rather building a purposeful, useful program assessment based in inquiry and practice.

During the next year, we convened as a faculty to review student portfolios, sometimes focusing on a predetermined issue but often simply reviewing sample portfolios and discussing them. We tried to get as many of our fifty adjunct faculty to participate in at least one of the sessions, paying them for their time. Over the course of these formative assessment workshops, we rewrote the learning objectives of the writing program course sequence to reflect the specific classroom and practice-based concerns of the instructors. We then asked faculty what sort of questions they would pose about the curriculum and what methodology they would use to answer the questions posed. Eventually, this became our ongoing process. In a typical semester we might be running a syllabus review to see how many faculty were doing all of the prescribed assignments, conducting a faculty survey to determine the purpose of the assigned readings in the writing courses, and doing a portfolio evaluation on whether students were learning how to construct a solid argument or use research well. Since the faculty were involved in the process so completely, our assessment initiatives worked concurrently as faculty development, offering writing instructors an opportunity to convene in an analytic tête-à-tête about the overall curriculum, but also to critically review their individual pedagogical practices. Instead of a mere conversation about “best practices,” we had a more richly expansive symposium about “best insights” into our programmatic work.

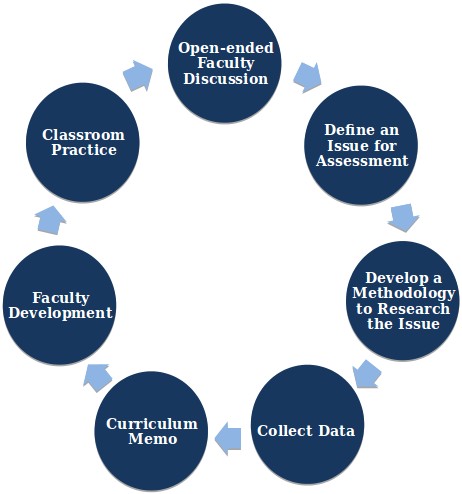

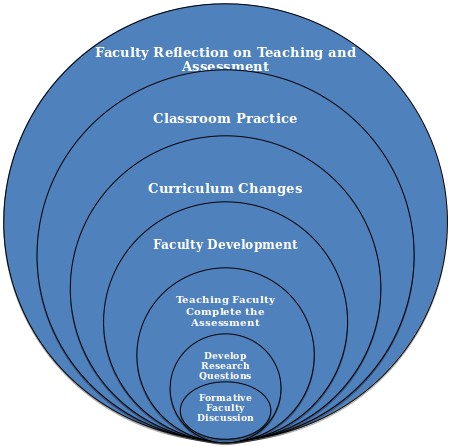

To make a further connection between our assessment practices, our faculty, and student learning in the classroom, we aligned our faculty development plan with our assessment plan. Instead of faculty development on broad topics like responding to student writing or classroom management, our faculty development work (done through workshops or peer mentoring) would focus on the specific issues listed in our self-imposed curricular to-do list, which came from our assessment. These workshops helped our large, experientially diverse faculty meet the curriculum changes at the level of classroom praxis. Over time and to our benefit, we have changed the simplistic linear, one-time, product-producing model of assessment (presented in figure 2) into an ongoing cycle of practices that was process generated and classroom focused. Figure 3 below represents the outcomes assessment process our writing program undertakes each year. In a recursive cycle of activities, the composition faculty{5} suggests possible areas for assessment and, perhaps, a research method for each target, and then a smaller group of 3-5 faculty, who we have come to think of as an assessment committee, designs the assessment, collects and evaluates necessary data, and helps the writing program director write up the results, which are then translated into curricular/pedagogical/programmatic changes. Changes to the curriculum, resulting from program assessment, are supported by faculty development, and the assessment is repeated the following year to see if the improvements have transpired.

Figure 3. Circular Classroom-Based Formative Program Assessment Process.

Each year we repeat this program assessment cycle, confirming the changes we have implemented and identifying additional curriculum areas to improve. With this ongoing process of amelioration, we become more cognizant of our programmatic make-up, which allows us to define and re-define ourselves as well as more carefully articulate this programmatic identity to our instructors, to our colleagues in other disciplines, and, most importantly, to our students.

Assessment Process in Practice 1: Looking for Consistency

Despite the hiring of new full-time faculty, adjunct faculty still taught more than 70% of the sections in our FYC sequence when we launched our new writing curriculum. Though many of these faculty had participated in program assessment workshops, we could not be certain how consistently faculty were teaching the new curriculum. We were not sure if instructors were applying the same learning objectives, requiring the prescribed assignments, and focusing on the program’s main curricular concepts. When proposing consistency within a writing program, an immediate friction surfaces between an administrative desire for control, enabling all students to have to have the same experience, and the necessary importance of maintaining faculty creativity and ingenuity. These two extremes between curricular free-for-all and authoritarian “managerialism” challenged us to initiate programmatic assessment practices that could fulfill these two somewhat contradictory goals. In other words, our program assessment process presented us with openings for faculty-led improvement rather than a policing mentality where evaluators search for lawbreakers and/or subsequent juried findings are praised when they meet static goals.

Rather than create narrow guidelines for our “prescribed assignments” in ENG 101 so that we could easily conduct summative quantitative assessment on the resulting student written products (a standard assessment move), we held faculty development workshops on the prescribed assignments to show how these internally cohesive structures are flexible and open-ended, allowing faculty to create their own versions of assignments and to arrange them in their own sequencing. We made it clear that we did not want all of the instructors to have the exact same assignments or even to schedule the assignments in the same order. With some teacherly ingenuity, any number of pedagogical approaches could take place within our curricular structure. During these workshops, it became clear that some faculty had a weak understanding of the learning objectives for particular assignments. This assessment led us to ask faculty in the workshops to design and share versions of the prescribed assignments, which of course served to increase curriculum consistency.

We held similar workshops on the purpose and practices of assigning and responding to portfolios and another set of workshops on WAC/WID and rhetoric for ENG 201. So our formative assessments were truly formative, enabling faculty to learn and grow as they evaluated for themselves, in relation to their colleagues, how well they were teaching the curriculum. In all cases, we wanted to promote flexibility and creativity, and to acknowledge and celebrate the proficiency and creativity of our adjunct and full-time colleagues. In the end, our faculty development illustrated how pedagogical license within certain designed parameters could in fact encourage creative lesson planning while sustaining curricular integrity.

With this movement toward curricular consistency in place, we could then carry out syllabus review that was not punitive. For example, when we discovered through syllabus review, that only 50% of faculty in ENG 201 were completing a portfolio, we responded not by sending out a mandate that all must do so or face a penalty of some sort, but rather we made sample portfolios available to faculty for review and used them to hold workshops where assignments, especially reflective writing, were discussed. Rather than creating an atmosphere of “administrative coppery,” assessment had become a process of discussion and change where faculty were given the latitude to move the curriculum forward, rather than freezing it in place. The ultimate result was increased consistency over a broader range of possibility. Rather than succumb to the skeptical scrutiny of our writing faculty, the assessment process involved faculty to include their recommendations, thus confirming and re-energizing their pedagogical efforts. By combining a traditional form of program assessment, the syllabus review, which could be used as an adequate initial assessment device to produce quantifiable data for assessment reports, with active faculty development, we were able to actually foster classroom practice rather than just enforce the inclusion of learning objectives on a syllabus, despite what was happening in the classroom. Here and throughout the assessment process, while we collected quantitative data, the goal was to use the data to inspire discussion and movement toward curricular change. (For the complete syllabus review data, see Appendix 4.)

Assessment Process in Practice 2: Enhancing Coherence

A tandem goal to curricular consistency across sections was to increase the coherence between the courses in our writing program sequence. In other words, though we had one set of learning objectives for the program, we wondered whether faculty and students were experiencing a carry over from one course to the next, the first course acting as a rehearsal for the second course and, subsequently, for the writing students will do in their content-based courses as well as careers. In Redefining Composition, Managing Change, and the Role of the WPA, Geoffrey Chase suggests some guidelines by which a university writing program can develop programmatic “internal coherence.” He states:

Internal coherence rests on a programmatic footing comprised of four components: (1) common goals specific and detailed enough to be meaningful and useful, (2) common assignments, (3) standard methods for evaluation and assessment across multiple sections, and (4) a commitment to examining and discussing these shared features openly. In one way, planning for internal coherence is the easiest part of what we do. It is the area over which we have the most control, and it is the facet of administration most directly linked to the training we receive as graduate students and junior faculty. (245)

We would contend that WPAs sometimes have little control over curriculum design, as many stakeholders want to offer their “expertise” to the conversation, but in order to build coherence, curriculum needs to be wedded to program principles, and the role of creating that coherence falls to the WPA, though, as we found out, not in a top-down role. Chase makes the connection between coherence and collaboration among stakeholders this way:

Moreover, when a program lacks internal coherence, the opportunity for collaboration and cooperation among instructors is limited. Everyone is on their own. It becomes nearly impossible to talk about the overall effectiveness of the program and, finally, it becomes nearly impossible to talk about composition as it is related to the larger educational experiences of students within the program. Internal coherence then is essential. (245-46)

Chase concludes that internal coherence places a level of accountability upon WPAs and the institutions in which they work and, if they genuinely want to invest in students’ postsecondary literacy acquisition and advancement, WPAs must devise a writing program in which the needs of the students, the institutional mission, and systemic constraints converge. But, most importantly, Chase advocates, and we would eventually follow, a model of coherence that builds from the classroom faculty up to the program objectives, rather than the other way around.

In our case, we certainly believed that our curriculum was designed with a strong coherent focus on the core concepts of inquiry-based writing, writing in and across the disciplines, rhetoric, reflective writing, etc. from ENG 100W all the way through ENG 201. However, in faculty discussions during assessment committee meetings we expressed our own insecurities about coherence. How much did we relate ENG 201 to ENG 101 in our own teaching? More importantly, did our students perceive coherence between the courses, especially since 85% of them took the courses in back-to-back semesters? As part of faculty discussions of program assessment, we were already formulating a focus group methodology, as we wanted to make student voices part of our ongoing assessment practices, and so we designed a series of questions to structure the focus groups (see Appendix 5) and we added coherence as a targeted question for the ENG 201 focus group. By asking these questions in our first focus groups of ENG 201 students, we learned that they felt very little connection between ENG 101 and ENG 201, some describing it as two completely different experiences, where ENG 101 was like a more difficult high school research paper course and ENG 201 was a more open-ended and freewheeling course.{6} Many commented on how they did a portfolio in ENG 101, but they did not have to do a portfolio in ENG 201.{7}

The students’ comments in focus groups confirmed our fears about the lack of coherence in the course sequence. To help build this coherence, we discussed this point with faculty, who suggested that maybe the opening of ENG 201 could be a carryover assignment from ENG 101. Following the “prescribed assignment” curriculum model that had been so successful in ENG 101, we broadly defined an assignment where the students’ ENG 101 portfolio would be used as an opening text in the English 201 course. The prescribed assignment required faculty to use student writing from ENG 101 to introduce the rhetorical focus of ENG 201 by basically asking questions: Just what was the writing you did in ENG 101? Who were you writing for (audience)? Why did you make the choices you did (genre and purpose)? As they did with prescribed assignments in ENG 101, individual faculty took this skeleton framework and came up with a variety of assignment possibilities. One version asked students to do a rhetorical analysis of their 101 work using ethos/pathos/logos; another required students to revisit an ENG 101 assignment and revise it into a different genre; and a third asked students to label the rhetorical moves they had made throughout their work (description, claim, evidence, etc.) according to their new rhetorical and composing knowledge gained early in ENG 201. Most importantly, faculty suggested that increased work with students on reflective writing and rhetorical analysis of their own work may give students the ability to better make connections between the classes. Since rhetoric and reflective writing were already key components of the course design, it was easy to reinforce these concepts with assignment design work in faculty development. Once again the connection between the structure of the new writing curriculum and our assessment practices were recursively impacting each other.

Assessment Process in Practice 3: Assessment and Learning

Now more confident that our curriculum had a consistent and coherent focus, and more optimistic and practiced with meaningful assessment, we proceeded with a more outcomes-based portfolio assessment. As you will see in the description below, by this point we had fully taken charge of assessment methodology and terminology. Unlike our first attempts at portfolio reading, the faculty readers took quickly to the norming process because the curriculum was much more familiar. The norming used low, medium, and high benchmark portfolios, and a five-point scale rubric of the faculty composed and revised first-year writing learning objectives. If student work was missing from any portfolio, making it impossible to rate the portfolio in a particular category, faculty evaluators were asked to enter a “0” or “could not be evaluated” in that category. As a rule, faculty members did not evaluate their own students’ portfolios. We used a random sample of the equivalent of 15% of the portfolios completed in that semester, and we followed the rules for validating readers by assigning second readers to a certain percentage of portfolios, achieving positive inter-rater reliability of .86 (.9 is considered excellent). In other words, we had overcome our initial trepidation about mastering assessment language and processes. Still the results startled us: not because we found the scores surprising in any way, but because we found them so uninformative.

Table 1. ENG 101, Fall 2011 Portfolio Evaluation.

|

Invention and Inquiry |

Awareness and Reflection |

Writing Process |

Claims and Evidence |

Research |

Rhetoric and Style |

Sentence Fluency |

Conventions |

|

2.86 |

2.87 |

2.96 |

2.67 |

2.66 |

2.79 |

2.90 |

2.86 |

When the “results were in” the faculty stared at them and said, well what do these numbers mean? It seemed like for post ENG 101, our writers were right where we expected them to be on the objectives on our five-point scale. Admittedly, students weren’t fully proficient but they had only completed the first of our two-course curriculum; they still had another semester to improve their writing proficiency. In our meeting, we did comment on the happy realization that the sentence fluency and conventions categories were actually above the other categories, thus disproving the all-too-often repeated mantra that “Grammar with a capital G” was the problem with our students’ writing. However, we had little more to say about the data. While this process provided quantitative numbers for the Middle States, we saw little benefit in it.

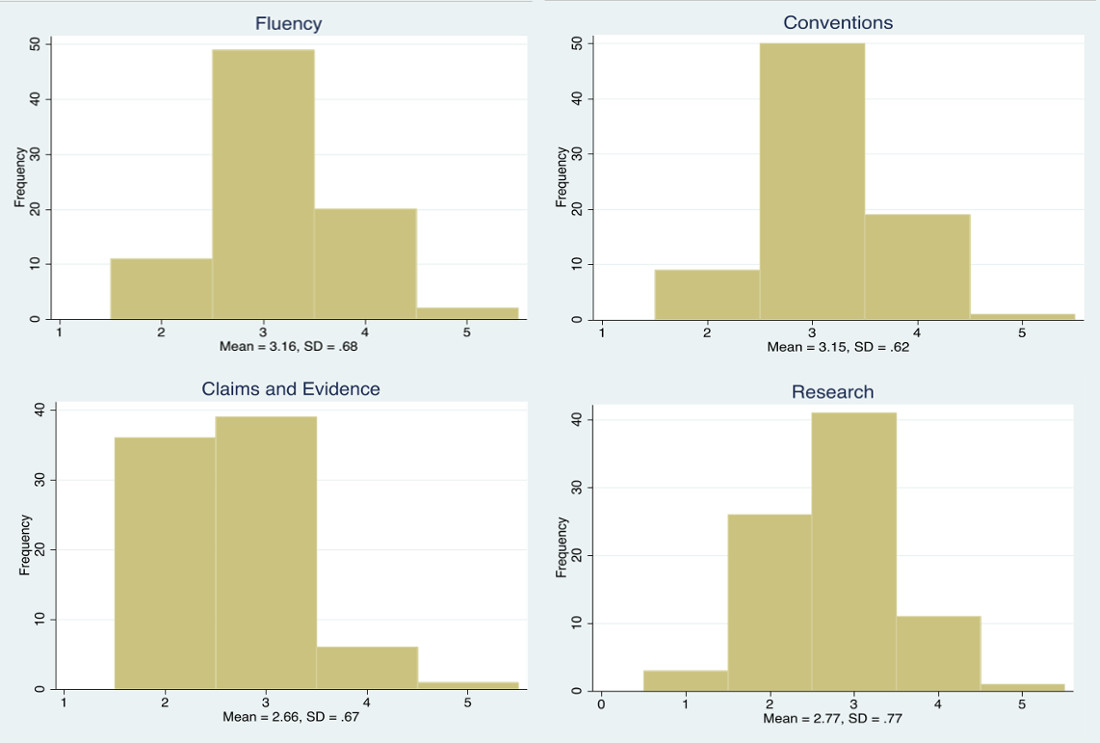

Instead, our portfolio reading had yielded something more valuable than numbers. During our conversations after the portfolio reading, faculty stated how disappointed we were in the research projects from the portfolios that we had read. At the time, we noted that too many students were doing extensive book reporting on what “the experts” had to say about an issue, rather than exploring their own inquiries into complex territory. So, while the data suggested that students were doing fine with their research and claims and evidence, we knew we were not happy with student engagement with their topics, nor with the complexity of the thinking their projects revealed. The result of these discussions was that in the following year we decided to focus more closely on the specific learning objectives of research and claims and evidence, as a way to improve what we felt were too many “information dump,” non-inquiry based student projects. In addition, we wanted to re-confirm the sentence fluency and conventions numbers, so that we could use them to thwart the critique that our student writers needed more skills-based work on grammar and sentence structure in our courses. Table 2 and figure 4 represent a sampling of the quantitative data from our second portfolio reading.

Table 2. ENG 101, Fall 2012 Portfolio Evaluation.

|

Sentence Fluency |

Conventions |

Claims and Evidence |

Research |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean |

3.16 |

3.15 |

2.66 |

2.77 |

|

Proportion 3+ |

.89 (+/- .06) |

.90 (+/- .06) |

.59 (+/- .11) |

.66 (+/- .10) |

Figure 4. Frequency/Mean ENG 101 Fall 2012.

As in the previous year, the new quantitative data confirmed that our writers were doing well in these areas and this quantitative data could be used perfectly well in the sound-bite world of assessment reporting. But again, the numbers seemed to simply suggest that all was well, with writers somewhere between some proficiency and full proficiency in all categories. Also, once again, however, it was the conversations the faculty had after the portfolio reading that provided a more specific focus for curricular change for our writing program. This time faculty mentioned that some of the student portfolios had included primary research along with the secondary source work, and that these were often the stronger research projects. Faculty debated the connection between primary research and inquiry and the requirement of primary research in ENG 101 as an excellent rehearsal, and coherent link, to ENG 201. Since we now realized that the discussions held after the portfolio readings were just as important as the quantitative data, we “videoed” the conversation of the faculty readers after the portfolio evaluation and included it as meaningful qualitative data from expert readers.

There were additional benefits to our investment in summative outcomes assessment data collection that also had a formative program improvement focus. Since full-time and part-time instructors completed this portfolio reading together, they were able to see and discuss a variety of portfolios, creative assignments, and ways of structuring the course. For less experienced instructors this process provided some pedagogical tactics for making their instruction more robust; for more seasoned instructors it provided an opportunity to hear the creative ways that other instructors designed their courses and assignments within the parameter of the curriculum. The portfolio evaluation once again reinforced the idea that assessment, when done by faculty, is a powerful form of faculty development. We carried out this curriculum change through the use of a curriculum memo that would go out to the entire faculty at the start of each semester and would provide recommendations and requirements for faculty to follow (see Appendix 6). Once again, the curriculum memo would be followed with faculty development workshops centered on the core recommendations and requirements in the memo.

In subsequent years, we continued this process of quantitative and qualitative data collection, with the latter conversation often directing the kind of assessment we did the following year. For example, one year we did a comparison between the Learning Community and Traditional versions of our 101 courses. In another year we designed a study of the amount of reading and the kinds of readings that were being assigned in the composition courses.{8} These focused attempts represented the faculty’s complete control of the process. We were no longer simply responding to the need for quantitative outcomes assessment report data for Middle States, though we were providing that data. But we were also achieving something more valuable: an ongoing, progressive assessment that was impacting our pedagogy and curriculum each year.

Moving Beyond a Linear Immobile “Snapshot” to a Recursive Moving Vision

If we have learned anything during our ongoing assessment of first-year writing at John Jay, it is that our assessment practices mirror the core learning objectives of our writing program: that research should be inquiry-based and based on primary sources that then lead to broader and more expansive questions. Assessment works better when faculty are motivated to conduct assessments that answer questions that they are interested in, and assessments, like research should be thought of as open-ended, not intended to get a final answer to any one final question. Figure 5, below, represents our current assessment process and illustrates how positing beneficial classroom practice as the destination point for assessment creates a positive ripple effect over the whole process. In the past four years we designed a survey of our ESL students to determine if they were better served in a specialized section of ESL or in a mainstream composition course; we combined syllabus review and faculty survey data to determine how much writing in the disciplines and writing across the curriculum work is being done in our ENG 201; and a study of reflective writing that has now headed into its second year, as we attempt to improve this crucial aspect of our curriculum. We include all of this data in our annual assessment reports for the college, though it is way more than what they ask for. The result is that we have an ongoing supply of data-based results and qualitative discussion that can be used to talk persuasively back to the latest critiques of student writing at our college. It is also easy to note how, as the faculty have taken control of the assessment process, and as our assessment research has grown in length and sophistication, the voice in our reports has simultaneously gained authority.

Figure 5. Recursive Wave Writing Program Assessment Process.

More accurately rendering our assessment process, the waves in figure 5 should actually be placed inside a walled container to indicate how the waves move outward from faculty led discussion about writing, but then rebound backward over the process. This ripple effect remains recursive with discussion and data rolling back and forth across each other, taking us in quite different directions than we intended. Each academic year we begin a new assessment wave, but the preceding waves continue to churn and resonate as shifts in institutional expectations also change.

In Looking Back as We Are Looking Forward: Historicizing Writing Assessment, Kathleen B. Yancey suggests that writing assessment had an initial wave of objectively scored grammar and usage tests, a second wave of holistically scored essays, and a third wave of criteria-based portfolio evaluation and program assessments. As writing assessment has evolved, writing faculty have assumed the expertise to assess with “a reliability based not on statistics, but on reading and interpretation and negotiation” (492). In her article, Yancey makes the same case we do: the purpose of assessment should be as a means to produce better student learning through better curricular and pedagogical practices. Our three years of program assessment have reinforced Yancey’s principles: (1) writing assessment that focuses on the process of assessment, on what faculty learn from doing the assessment rather than on the product of the assessment; (2) teachers have the expertise to take charge of assessment, and modulate the assessment to their programs’ context and purposes and (3) that all assessments need to be tied directly to a curricular purpose. (494)

Our waves of assessment have revealed both the strengths and challenges of our first-year writing program and increased instructional awareness about the goals of the curriculum. What we learned along the way is what Richard H. Haswell and Susan Wyche prescribed over a decade ago: “We discovered, perhaps mostly by luck, that the real site of writing assessment is not so much a battle zone or a contested economic sphere of influence as a territory open for venture, and that writing teachers will do well neither to accept passively nor to react angrily—but simply to act” (204). Acting is inherently optimistic. For writing programs, especially in urban, publically funded institutions that constantly face budget constraints and remain under ever-vigilant public scrutiny, faculty need to take charge of assessment programs to not only preserve existing programs but to enhance and improve them. We wanted to stop taking the defensive position, reacting to each new call for legitimacy, and instead build in the justification and validation of our work with student literacy, so that we could answer future calls for review without starting our justifications from scratch. When confronted with the “What are you doing in that writing program?” and “Why can’t these students write?” interrogations, we would have some data-based answers—both quantitative and qualitative—with which to rejoin, and offer alternative views of our students’ composing abilities and our writing curriculum.

Without an equal opportunity (consistent and coherent) course design and structure, the type of assessment we have done could not have occurred and, equally, without recursive assessment the program could not have sustained or improved itself. The symbiosis between our curriculum and assessment has given us a more concrete and transparent comprehension of our curricular objectives and actions. As equal and opposite (not oppositional) forces, our skepticism about our writing program alongside our optimism about its possibilities brought to the surface many of our assumptions, presumptions, and sometimes complete oversights. The assessment process revealed our weaknesses and flaws but did not deflate our efforts to improve. The systemic structure of the assessment process we have implemented enables us to legitimately and confidently explain our curriculum and validate our successes, but more importantly, faculty-led program assessment facilitates the evolution of our writing program in an ongoing and progressive way that enables equal opportunities for all our students.

Appendices

- Appendix 1: ENG 101 and ENG 201 Curriculum

- Appendix 2: John Jay College Writing Program Learning Goals (2006)

- Appendix 3: John Jay Writing Program Revised Learning Objectives (2010)

- Appendix 4: Spring 2013 ENG 201 Syllabus Review Data

- Appendix 5: Focus Group Description and Protocol

- Appendix 6: Curriculum Memo Resulting from Program Assessment

Appendix 1: ENG 101 and ENG 201 Curriculum

ENG 101 Prescribed Assignments

- A Descriptive Letter or piece of Creative Non-fiction that addresses the theme of the course.

- A Proposal that defines an investigative question.

- An Annotated Bibliography that identifies the expert discourse that has been previously studied by other authors and resources.

- A First Draft that messily lays out students’ ideas about their proposed topic.

- A Working Outline that designates the organization of their developing paper.

- A Scripted Interview that asks students to choose two authors they cite in their essay and compose a hypothetical interview. Acting as a participating interviewer, students must pose questions that both ask these expert voices to inform questions about their topic as well as elicit discussion between the two expert authors.

- Redrafts of their inquiry-based paper that accumulates evidence, organizational strategies, and synthesis of ideas that they have deduced/induced from their work on the various scaffolded assignments.

- A Cover Letter written to their second-semester composition instructor which explains their profile as a writer: what were their writing aptitudes like when they entered the first semester course, what they learned/improved about their writing, and what challenges they plan to work on in their upcoming writing course.

ENG 201 Prescribed Assignments

- A reflective writing/rhetorical analysis assignment that asks students to review, analyze and explain the “revision” they did for their 101 portfolio. (Added in after the initial curriculum design.)

- Writing projects in at least three different genres/disciplines.

- A rhetorical analysis essay/exam at the end of the course (In the process of being added into the curriculum.)

- A portfolio and a cover letter.

Appendix 2: John Jay College Writing Program Learning Goals (2006)

English 100W

- Students increase knowledge about the issues of literacy as a topic to be studied.

- Students are introduced to the literacy practices and habits expected in college.

- Students prepare for the rigors of college-level writing courses.

- Students engage with academic challenges, which stimulate their intellectual abilities and creativity.

- Students understand the structure and expectations of the ACT Writing Exam.

- Students practice low-stakes writing (informal, exploratory writing) and high-stakes writing (formal, finished products) related to the incremental and developing stages of the writing process.

- Students practice in various strategies of in-class writing such as mapping, freewriting, inkshedding, and peer critique.

- Students increase rhetorical language and self-awareness about their literate abilities that allow them to discuss their strengths and challenges of expression.

English 101

- Students learn and practice academic techniques to help them in the process of preparing research papers.

- Students practice both low-stakes writing (informal and ungraded exploratory writing) and high-stakes assignments (formal, finished products). The variety of writing assignments will give students the opportunity to experience the incremental and developing stages of the research and writing process.

- Students are familiarized with academic forms (letter, proposal, outline, annotated bibliography) to help them explore their investigative questions.

- Students learn the terminology and process of research.

- Students learn to examine their investigative inquiries within the discourse of their academic community as well as within the context of experts who have posed similar questions.

- Students learn to focus an investigative question and to prepare a statement, which describes their proposed inquiry.

- Students learn methods of library research, including finding books and journals appropriate to their subject, locating articles on electronic sites, and distinguishing websites that provide valid information and support.

- Students explore their ideas and think more critically through classroom discussions and exercises.

- Students learn to differentiate between speculation, opinion, analysis, and inference.

- Students practice in-class peer review to grow increasingly aware of audience, readers’ expectation, and the rhetorical devices necessary to convey ideas clearly.

- Students gain the language and self-awareness about their literate abilities that allow them to discuss their strengths and challenges of expression.

English 201

- Students practice varying processes and conventions of writing as it moves from field to field.

- Students learn different types of research methods and writing that they will face in the content-based courses of the college.

- Students consider how writing can help them learn new discipline-specific subject matter.

- Students learn to identify the preferred genres, rhetorical concepts, terminology, formatting, and specific uses of evidence in various disciplines.

- Students review research methods, conventions, and practices that they integrate into the cross-disciplinary writing assigned for this course.

- Students reflect upon how their composing skills can be applied in diverse writing situations.

- Students expand their abilities to discuss their writing strengths and challenges.

Appendix 3: John Jay Writing Program Revised Learning Objectives (2010)

(Note: This set of program learning objectives were developed from program assessment and replaced the individual course goals presented in Appendix 2.)

Invention and Inquiry: Students learn to explore and develop their ideas and the ideas of others in a thorough, meaningful, complex, and logical way.

Awareness and Reflection: Students learn to identify concepts and issues in their own writing and analytically talk and write about them.

Writing Process: Students learn methods of composing, drafting, revising, editing, and proofreading.

Rhetoric and Style: Students learn rhetorical and stylistic choices that are appropriate and advantageous to a variety of genres, audiences, and contexts.

Claims and Evidence: Students learn to develop logical and substantial claims, provide valid and coherent evidence for their claims, and show why and how their evidence supports their claims.

Research: Students learn to conduct research (primary and secondary), evaluate research sources, integrate research to support their ideas, and cite sources appropriately.

Sentence Fluency: Students learn to write clear, complete, and correct sentences and use a variety of complex and compound sentence types.

Conventions: Students learn to control language, linguistic structures, and punctuation necessary for diverse literary and academic writing contexts.

Appendix 4: Spring 2013 ENG 201 Syllabus Review Data

|

Yes |

No |

Somewhat |

Unclear/Not Indicated |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Learning Objectives included |

93.33% |

6.67% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

|

Learning Objectives match Writing Program Objectives |

33.33% |

66.67% |

0.00% |

0.00% |

|

Writing assigned in the disciplines |

60.00% |

13.33% |

6.67% |

20.00% |

|

Reading assigned in the disciplines |

73.33% |

13.33% |

0.00% |

13.33% |

|

Research Project assigned |

73.33% |

6.67% |

0.00% |

13.33% |

|

Rhetorical Analysis Essay assigned |

33.33% |

46.67% |

0.00% |

20.00% |

|

Midterm Portfolio Submission assigned |

6.67% |

80.00% |

0.00% |

13.33% |

|

Final Portfolio submission assigned |

80.00% |

6.67% |

0.00% |

13.33% |

|

Handbook required |

26.67% |

66.67% |

0.00% |

6.67% |

|

Exercises Assigned |

Instruction Listed |

Neither |

||

|

Explicit grammar or sentence work |

20.00% |

6.67% |

73.33% |

|

|

All Students |

For Revisions |

If referred |

Mentioned |

|

|

Writing Center required |

20.00% |

0.00% |

60.00% |

20.00% |

Appendix 5: Focus Group Description and Protocol

(Note: Description taken from assessment report, 2011-12)