Composition Forum 42, Fall 2019

http://compositionforum.com/issue/42/

Building Structure and Thinking Design in First-Year Composition

Abstract: The article provides an account of the author’s experiment asking first-year students at a STEM university to represent academic essay structure as three-dimensional models built out of unconventional materials, such as cardboard, foam, felt, and glue. The author documents her students’ process of working with their hands in a workshop environment to translate academic writing into artifacts neither academic nor written. Through visual and verbal examples of student work, the author shows how students use the activity to analyze how abstract concepts such as structure, form, and design translate across materials and modes. The experiment suggests that activities asking students to theorize, apply, and transfer concepts across media and learning styles offers a way to connect writing to design-related initiatives across the curriculum.

In their 2014 article Composing the Carpenter’s Workshop, James J. Brown and Nathaniel Rivers imagine what composition classrooms might look like in the future:

It is November 2015, and you are visiting what you thought was a college composition classroom. However, something seems to be amiss. In one corner, a group of students pass around a long wooden cylinder that they constructed using a lathe (they were able to get help from a professor in the Art department to gain access to the equipment). In another corner, a group huddles around a 3D printer as a strange looking blue plastic object emerges (it looks like a helmet). You find out from the professor (an excitable, bespectacled man with curly hair and a wry smile) that a third group is not present; they are across campus working with a group of architecture students and blowing glass. This happens a lot in this particular class. The English department has not yet approved the professor’s grant proposal for a workshop that would offer students the ability to work in various media. The proposal has been met with curious stares thus far, but the professor is undeterred. (33-34)

The authors suggest that all of these activities—turning wood, 3D printing, blowing glass—should be included in a capacious definition of what writing is, what it can produce, and what its objects of study encompass. By designing and making material objects that are integrated with their writing on the typed page, these imaginary students learn that human expression and communication can take many forms, even those that do not yet exist.

It is October 2017 (the future of Brown’s and River’s future class), and I walk into my college composition classroom at a private STEM university in the Midwestern United States. In my right hand, I’m holding the handle of a plastic box filled with twelve pairs of scissors, sheets of felt, index cards, and glue. Under my left arm, I’ve tucked a stack of cardboard boxes and foam boards, pieces of which are now threatening to spill out onto the floor. The students eye me suspiciously, but I am undeterred.

I drop my materials onto a desk in the middle of our circle of desks, proud of having made it up the stairs from my office without dropping anything. Soon, the students are measuring, slicing, stacking, and pasting, heads bent in deep focus. They are making material structures that represent the verbal structures of their arguments. They are discovering what new shapes their writing can take when the words become physical objects. They are composing, and later, they will write about these compositions in other compositions.

This article provides an account of a class activity called The Laboratory of Writing’s Architecture (LabWritArch), which I designed and tested in my first-year composition course during the fall semester of 2017. LabWritArch takes a metaphor I often use in my teaching—building structure—and turns it into a hands-on classroom activity that uses physical manipulatives to illustrate connections between writing and design. Like the students in Brown’s and Rivers’s imagined classroom, my students worked with their hands to craft compositions that reinterpreted the writing they produced with words. LabWritArch transforms the writing classroom into a place where students investigate what it means to design purposeful compositions—written in words and built out of nonverbal materials—and how to translate their ideas between verbal and nonverbal modes. The activity encourages students to attend to the design decisions required in performing translations between modes, as well as the decisions required in creating purposeful designs in the first place.

In providing this account of LabWritArch, I hope, on a practical level, to give fellow writing instructors an easily reproducible and adaptable activity that encourages students to reflect on the structure of their writing in a creative and engaging way. I designed LabWritArch to require only the use of fairly inexpensive and readily available materials and to be an activity that can be implemented at many points in the writing process (while brainstorming or drafting, for peer review or self-review, after a final draft is turned in, etc.).

On a theoretical level, the account acts as an example of how to use the classroom to explore what writing could mean if we thought of it as one of many forms of purposeful design. My contentions are 1) that teaching writing through the lens of design offers a way to connect writing to design-related initiatives across the curriculum, especially at non-liberal-arts colleges and universities where writing instructors struggle to make the case of writing’s relevance to students and colleagues; and 2) that teaching writing as design using material objects appeals especially to students who do not consider themselves “writers.”

After summarizing what other scholars have said about reconceptualizing writing as design and explaining how I came to see this re-cognition of writing as an important endeavor at a STEM university, I describe how I created LabWritArch and deployed it in my first-year composition course. I reflect on how LabWritArch revealed surprising insights into how my students interpreted the concept of structure in writing, and how they reflected on their own written products and writing process. I conclude with thoughts on how teaching writing as design might contribute to the question of what ideas we want students to transfer from our courses to other learning experiences. Through translating the form and shape of academic writing into artifacts neither academic nor written, my first-year students used design to navigate between form and content, analysis and process, writing and making.

Reimagining the Writing Classroom as a Design Space

Several R/C scholars have considered how design has influenced the theory and practice of teaching writing. In What Can Design Thinking Offer Writing Studies? James Purdy identifies five primary ways in which composition has adopted elements of design: 1) as a synonym for plan or structure of a particular activity, course, program, or research project; 2) to focus on the production and consumption of multimodal texts; and especially 3) digital texts; 4) to emphasize the materiality of texts, or the design of the textual artifact itself; and 5) to argue for writing studies’ benefit from closer association with the field of design studies and its focus on process. All of Purdy’s categories point to the idea that design’s most valuable contribution to writing studies is its emphasis on creation. Creation helps to move writing studies away from, say, literary studies, and composition’s fraught historical association with English departments. If literary studies emphasizes analysis, contemplation, and comprehension, then writing studies as seen through the lens of design emphasizes making, doing, and craft.

Richard Marback has suggested that this attention to design and its emphasis on creation marks the discipline’s return to process studies from the “critical theory and ideological critique” approach popular in the 1990s (397). Marback identifies James Berlin’s Rhetoric and Ideology in the Writing Classroom as the publication that “changed the landscape of composition studies” (397) from a discipline primarily interested in “accounting for the activity of composing itself” (397) to one focused on theoretical questions of authority and domination, agency and politics, and critical analysis (398). Marback also argues that it was Diana George’s article From Analysis to Design and Charles Kostelnick’s Process Paradigms in Design and Composition that “rearticula[ted]” composition’s object of inquiry as the act of writing itself, particularly student writing, and swung the pendulum back in the direction of process (398). Richard Buchanan also articulates the affinity between design and rhetorical studies as a shared attention to the creative process: “design—as the intellectual and practical art that provides discipline in the creation of the human-made world—employs rhetorical doctrines and devices in its work of shaping the products and environments that surround and persuasively influence our lives” (187). Geoffrey Sirc and Todd Taylor argue for the importance of creating classroom spaces that make creative thinking possible and necessary for composing, while Anne Wysocki advocates for the creation of “unavailable designs” (59)—textual artifacts designed in ways that defy readers’ expectations and assumptions—as part of the composition curriculum. Thus, design, and its emphasis on the creative process, has long been a touchstone, even a bellwether, by which and with which composition studies has defined itself.

Recently, Carrie S. Leverenz has built upon Marback’s use of design as the bridge between critical theory and process analysis by proposing that we think of writing instruction itself as a problem best approached through the language and pedagogy of design. Drawing on The New London Group’s call for redesigning education on the principle of “restoring student agency through acts of making” (5), Tim Brown’s conceptualization of design as a problem-solving process, and Lucy Kimbell’s understanding of writing as a design practice, Leverenz suggests that we teach writing “with a focus on creativity and innovation and on designing texts that contribute to designing the future” (5). Teaching students to become “designers of writing” (10) would combat the bugbears common to first-year composition: “the deadness of teaching academic writing with a focus on conventions, a lack of student engagement in school writing, and our compliance with the limiting educational mission of maintaining academic standards” (5).

In practice, “reimagini[ing] writing courses as a space for design thinking” can take many forms, but Leverenz suggests one that I find especially helpful as an instructor and WPA at a STEM university. Leverenz suggests designing assignments containing “meaningful constraints,” such as “the constraint posed by having to translate writing into visual representations” (7). Referencing Laurie Gries’ and Collin Brooke’s experiment of having students translate a research project into a slideshow using architecture software, Leverenz writes that such acts of translation “led many students to think about their research in new ways” (7). In addition, Leverenz suggests asking students to “work on their ideas in different media,” through, for instance, storyboarding, sketching, modeling, and otherwise “thinking with their hands” (10). Giving students the opportunity “to play with modes in the service of working on ideas” helps them to “break out of habits of linear, analytical thinking and allow[s] them to see their ideas in new ways” (10).

Manipulatives and the STEM Student in the Writing Classroom

I first came across the literature on the intersection between design and writing studies while trying to address similar issues to those Leverenz mentions—teaching composition as a series of conventions, student disengagement, and the limited perception of what writing is, and what students in writing courses should be asked to do, at STEM-focused institutions. As a WPA at such an institution, I struggle with instructor burnout and lack of retention due to such issues. In addition, I had been searching for ways to make composition relevant, even integral, to the University’s flagship programs in engineering and architecture, both of which emphasize design in their curricula. I wanted to revivify our first-year writing curriculum with assignments that touched design initiatives across the university and provided the critical thinking and writing skills fundamental to student success in those initiatives.

Leverenz’s suggestion to have students work in different media, play with modes, and manipulate materials with their hands resonated with my sense of what would appeal to students at my university. In the STEM environment, students encounter many opportunities to use manipulatives to create three-dimensional models representing systems too difficult or expensive to build in a classroom. Research also suggests that material objects help students strong in spatial intelligence, as STEM students often are, to visualize the components of their writing more coherently. Linda Hecker, whose work focuses on learning-disabled students, writes of her experience with “building strategies,” in which “students construct three-dimensional models that show how ideas relate to each other” (47). Hecker writes:

For students with strengths in spatial intelligence, manipulatives may be the strategy of choice. [...] Spatial intelligence involves the ability to perceive patterns and arrays and to conceptualize ideas dimensionally, as in understanding how the parts of something go together to make the whole. Architects, engineers, designers, and many scientists possess a high level of spatial intelligence. Students who are often doodling or cartooning, who love to build models or make charts, or who know how to take apart an object and put it back together without looking at a diagram or manual can be good candidates for these strategies. (49)

At my university, the majority of students hope to become architects, engineers, designers, and scientists after graduation. I have observed that many of my students are attracted to building models and studying mechanisms with an eye to disassembling and reassembling them, so using manipulatives with them seemed a natural fit. The use of material objects in a composition class emphasizes the connections between writing and making, and by doing so, appeals to students who do not consider themselves writers but have aptitude and interest in design.

Scholars of multimodal composition and the intersection between rhetoric and object-oriented studies have also shown interest in how manipulatives play a role in the writing classroom. Brown and Rivers’ notion of “rhetorical carpentry” (29){1} highlights the importance of using physical objects to create other objects that respond to conversations within and outside the classroom.{2} Jody Shipka has called for a more expansive notion of multimodality in composition instruction that goes beyond the field’s focus on digital media to embrace material objects. Her own experiments with having students incorporate in their compositions such unconventional materials as ballet shoes, mirrors, “advice manuals, textbooks, children’s books, film, art, bumper stickers, print newspapers and magazines, toys, candles, jewelry, and other objects” (Multimodal 303), suggests that manipulatives have an important role to play in the future of composition instruction, even in our increasingly digitally-saturated environments.{3}

Returning to Structure and Discovering an Example

Engaging with the literature that conceptualizes writing as design helped me realize that for students at non-liberal-arts institutions who think of themselves as “bad at English” or uninterested in the humanities, changing the way we present the nature and purpose of composition might help break down their barriers to writing. And so my objective began to clarify: I wanted to transform the writing classroom into a design workshop through the use of manipulative material objects. But the question remained as to what, exactly, to have the students build. How to anchor the students in a concept that might blur the distinction between writing and design and help them see the significance of their creativity in both?

After some thought, I decided that revisiting structure, Purdy’s first category of design’s influence on writing studies, was a good place to start. Many times as I’ve stood in front of a classroom full of engineering students waiting to hear an explanation as to why my class should matter to them, I have found structure a helpful concept with which to establish common ground. I explain that structure unites all kinds of purposeful creation: if, in academic writing, an essay’s structure communicates the writer’s intention to his or her audience, so too does the structure of an engine, a robot, or medical device allow that mechanism to achieve its purpose, the structure of a building allow it to stand, the structure of a highway make travel possible. I emphasize that structure is the result of decisions made by creators: one decides to construct an automobile or a building in certain ways for certain reasons, and so, too, an essay. As a concept that spans and bridges many disciplines, structure has proven to be a useful point of reference for talking about how writing relates to other majors, as well as provide a key to demystifying the kinds of essays I ask my students to produce.

In attempting to come up with an activity that used manipulatives to explore structure in the service of reimagining writing as design, I reached out to a colleague whose interests coincide with my own. She brought to my attention an ongoing project operating outside of traditional academic circles that nevertheless spoke to concerns brought up within the academic literature. She suggested I look up the Laboratory of Literary Architecture (LabLitArch), a travelling workshop created by architect/author/illustrator Matteo Pericoli. In 2013, Pericoli wrote a short essay called Writers as Architects for The New York Times’ Draft, a series of articles on the art and craft of writing. In the piece, Pericoli describes the LabLitArch in this way:

Great architects build structures that can make us feel enclosed, liberated or suspended. They lead us through space, make us slow down, speed up or stop to contemplate. Great writers, in devising their literary structures, do exactly the same.

So what happens when we ask writers to try their hand at architecture? At the “Laboratory of Literary Architecture,” [...] I encourage students to find—or, rather, extract—and then physically build the literary architecture of a text.

Each [creative writing] student brings to class a novel, a short story or an essay whose inner workings he or she knows intimately. We start with the plot, the subject or simply a feeling that the student has about the text. We break the piece of writing down into its most basic elements and analyze the relationship of each part to the overall structure, making sure to avoid any literal translations of the text [...].

The exercise is a process of reduction. In architecture, once you remove the skin—the ‘language’ of walls, ceilings and slabs—all that remains is sheer space. In writing, once you discard language itself, the actual words, what’s left?

In his workshops, Pericoli pairs a creative writing student with an architecture student, and together, they construct—out of cardboard, scissors, glue, pieces of glass, and other raw materials—a three-dimensional model that expresses the “literary architecture” of the text. The images included in “Writers as Architects” present fascinating, multi-faceted sculptures—spatial forms inspired by textual forms. The workshop is a truly transdisciplinary analysis of what it means to compose a cultural artifact that is at once a thoughtful and a beautiful creation.

Pericoli uses LabLitArch to study, as the name suggests, how form takes shape in literature and architecture. The creative writing students they work with bring to the project their favorite novels and short stories by authors such as David Foster Wallace, J. M. Coetzee, and Raymond Carver. But LabLitArch’s unique take on thinking through design with respect to the written text, its emphasis on analysis through creation, and its correlations with the ways in which design has already penetrated writing studies, made me wonder whether one could adapt such a project to a non-creative writing course. Rather than using literature as the object to reduce, extract, and transform, why not use a student essay, even a beginning student’s essay in a beginning writing course, as the object of study and the inspiration for a new creation?

LabWritArch: Writing, Building, Designing in the STEM FYC Classroom

Thus armed with an objective (to rethink writing as design), a method of achieving that objective (workshop writing as design through manipulatives), a concrete task with which to implement the method (investigate structure as a concept central to all forms of design), and an example of how all of these elements could be brought together (LabLitArch), I created LabWritArch, named after Pericoli’s own project.

We were midway into the fall 2017 semester of my first-year composition course. As luck would have it, I had ended up with a class of twelve students, nine of whom were first-years in the architecture program. If nothing else, I thought, the activity would encourage these future architects to consider how the concept of structure crosses disciplinary boundaries and show them how thinking about writing as design in first-year composition might improve their ability to actually create thoughtful designs in their major courses.

On the day final drafts were due for their third essay, my students came to class having read Pericoli’s Writers as Architects and familiarized themselves with the LabLitArch website. During class, we read aloud most of “Writers as Architects” and analyzed the language Pericoli uses to articulate the project’s goals and procedures, as well as the images of his students’ work and the way they wrote about them. I directed the students’ attention to the materials I had brought to class and laid out in the center of the room: cardboard boxes, scissors, craft glue, masking tape, index cards, black felt, and foam board. I asked them to make physical three-dimensional representations or expressions of their essay’s structure, similar to what Pericoli’s students had done with literary texts. To facilitate the sharing of materials, I asked them to put two trapezoidal desks together to create small hexagonal tables, each of which could seat two to three students. Each student worked individually on his or her own structure using his or her own essay, but I did not prevent them from talking to one another or sharing design ideas.

Earlier in the course, we discussed body paragraph structure in terms of topic sentences, evidence and interpretation, transition sentences, and how these elements might be organized to comprise an effective body paragraph. We also discussed using counterarguments as a way of structuring one’s argument, both within and across paragraphs, and the many ways by which a writer might give “signposts” to readers to reveal the logic of their argument’s development. We talked about structure as both form and content, dependent on an essay’s objective, but also on audience expectations. These conversations were meant to act as tools in their carpenter’s toolkit, to be brought out and used when and if they saw fit. Because I did not instruct them to use a particular definition of structure by which to build their models, they were free to define the concept as they best understood it.

As the students worked, I did not notice much exchanging of ideas going on; the room remained very quiet and the students absorbed in their own labors. The room got so quiet, in fact, that I suggested playing some music to design by, and we all agreed on The Beatles, Simon and Garfunkel, and Van Morrison. As they worked away, I scrolled through images of student work on the LabLitArch website projected onto the screen at the front of the classroom to provide inspiration. Several students had drafting rulers, precision knives, and craft pins with them, and they brought them out to use without my prompting—and, noticeably, without asking whether they were allowed to use these extra materials. This, from students who, being freshmen, still asked to go to the restroom or get a drink of water from the fountain in the hallway.

What surprised me most was that the majority of students began building immediately, without sketching first. I expected a room full of architecture majors to reach for their sketchpads the moment I turned them loose. But it was as if the writing of the essay—the freewriting, drafting, and revising we had done earlier in the semester—took the place of sketching for most of the students. Those who did sketch prior to building did so on paper and laptops roughly equally. About half called up electronic copies of their essays on laptop screens and scrolled through them as they built. All, regardless of the procedure they implemented, worked right up until the end of class time on the first day, intently and with focused concentration.

On the second class day of the activity, I gave them forty-five minutes of work time and reserved the last thirty minutes of class for short oral presentations. As each student completed his or her model, I invited them to bring their structure into the hallway and set their structure on a bench outside the classroom, where I photographed it. After photographs of all the structures were taken, I asked each student in turn to show their model to the class and explain how to “read” their structure. Furthermore, I asked them to explain how it expressed, represented, or corresponded with the structure of their essay. The class then had the chance to respond, ask questions, and give feedback to the designer. In adopting this system, I wanted to mimic the procedure and environment of “the critique,” a practice common in studio classes at my university and others. I felt that utilizing the critique made the class feel more like a workshop and thus more design-focused.

The images and written commentaries below represent a selection of my students’ work. The selections are grouped into three categories according to the approach the student took when interpreting how to translate verbal into material structure. I created the three categories and grouped the structures according to them after looking at all of the models and listening to each of the presentations during the critique, and afterward, studying the photographs I took. The writings correspond to the students’ oral presentations, and I asked them to compose and send these writings to me by e-mail within a few days of the critique. Each image of a built creation is followed by the student’s writing about it. The images and writings are presented here with IRB permission, and I have changed all students’ names to protect their privacy.

Category A: Structures that Correspond to the Elements of Essay Organization

The structures I placed in this first category approached the assignment as one of translating elements commonly associated with academic essay form at the college level into shapes composed into a three-dimensional structure. In other words, every structure in this category sought to give physical shape to the same “building blocks” of an essay—the introduction, thesis statement, body paragraphs, transitions, conclusion. However, despite their common purpose, the structures look vastly different from one another. The existence of wide variation despite the use of similar tools is the way I have often explained to first-year composition students why what is sometimes termed “formulaic writing” need not produce formulaic essays, nor should composing with certain established structural models in mind limit the writer’s freedom to generate original ideas.

Figure 1. Anna’s Structure

“The structure that I built reflects the structure of the essay that I wrote. Starting at the top, the first triangular piece represents the thesis and introduction paragraph of my essay. Working your way down, the middle triangular piece is representative of my body paragraphs. And the last triangular piece is my conclusion paragraph. The small rectangular pieces connecting the triangles represent the connections between each argument in my essay, and how they all flow together. The shape of the triangular structures represents the broad topic of each paragraph that eventually condenses down into one argument.”

All the structures in this first category incorporate a sense of movement despite their use of static objects. A viewer of Anna’s structure must begin at the top level and follow the downward-sloping triangles as they cascade toward the bottom. Anna describes this movement as the viewer having to “[work] your way down,” and the “flow” of the triangles into one another. One gets the sense of separation and connection, stop and continuity, solidity and porousness. Anna writes of “broadness” and “condensation,” two concepts that also appear in the next student’s writing.

Figure 2. Karen’s Structure

“The top floor represents the leading statement in my essay, it is a broad statement so this floor is larger than the two below it. The next floor is slightly smaller, showing that my focus is beginning to narrow. The third from the top floor represents my thesis, which shapes the rest of the structure. The bottom floor represents my body paragraphs, which support the claims I made in the introductory paragraph and thesis.”

Karen’s structure narrows from the top down, just as the focus does in her essay. There is an interesting symmetry that occurs in Karen’s structure: as the top floors narrow, the bottom floor broadens out. The first segment of the bottom floor is the smallest, the second segment a bit larger, and the third the largest, but the shape of each of these segments remains the same; only the scale changes. Had she not balanced her structure in this way, it probably would not have stood upright on its own. Karen’s creation reveals that in both visual and verbal art, the interplay between broad and narrow, big ideas and focused examples, repetition and difference, contributes to the beauty and the structural integrity of the object.

Figure 3. James’s Structure

“The structure that I have created represents my essay in the way it was given a structured foundation to begin with, but loose in the way it was presented. My structure has three elements: the base foundation, the wire weave, and the pedestal. The essay was given a clear goal at the start by the thesis, hence the structure having a square-shaped foundation with little fluidity. The body paragraphs of my essay are what helped weave the essay to the conclusion, which is presented as the pedestal. The wires are close together as they reach the top pedestal, yet there is still a bit of looseness in the middle, to demonstrate the thinking in the analysis as not being “linear.” The pedestal is put high above the bottom foundation, as you are left with a higher level of understanding by the time you reach the conclusion.”

James’s structure cleverly uses a wire weave as a visual metaphor for the “weaving” of his body paragraphs toward the conclusion. Although each wire strand represents a single body paragraph, the ideas contained in all the body paragraphs intertwine. I am not sure if James meant for his characterization of the “looseness in the middle” of the wires to be a criticism of his essay, or whether he believes that non-linear analysis is less ideal than the linear sort. But the task of translating verbal structure to visual structure helps him to reflect on both what he wants his essay to do—his intentions—and what the essay does do, the result of the execution of those intentions, and the differences between them.

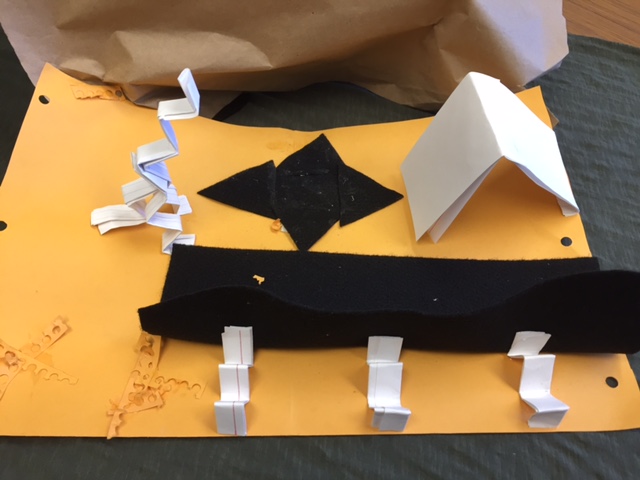

Figure 4. Brenda’s Structure

“My structure is meant to be read left to right, the same way a paper would be. The leftmost part is a piece of cardboard with holes in it, meant to represent the beginning of my introduction where I start to talk about the main idea of my essay and introduce the reader to the two readings discussed. Next comes the first set of stairs, which start out wide and narrow in the same way my introduction does. From the very top of the stairs is a direct bridge to the thesis, signifying the path my introduction takes to the main claim of my entire essay. The column, which represents my thesis, has a point at the top to represent the fact that my thesis is concise and unambiguous. Like my thesis, the center column supports all the floors of my structure. There are six of them, and there are six body paragraphs in my essay. While each floor is clearly distinct, the pieces of black felt connect them, much like the transitions and similar points between my paragraphs. The floors fan out around the thesis because my body paragraphs cover their own ground, but there is some overlap where ideas intersect. The smaller, shorter cardboard columns in my structure do not support the floors the way columns normally would. They pull the floors down instead of holding them up, to keep the structure from toppling over the other way. These represent my counterarguments because they are an opposite and nontraditional force, but they are used to stabilize and strengthen my structure all the same. On the far right side, there is the second set of stairs that are my conclusion. These stairs go from narrow to wide, showing how my conclusion expands back out and trails off, leaving the reader with something to think about.”

Brenda’s structure and writing evidence the most sophisticated development of a common language by which to articulate the forms that verbal and visual structures take. She talks about her visual structure as having to be “read” the way an essay must be read. Architectural elements—stairs, a bridge, columns that hold up and columns that weigh down—are used to express the relationships between different parts of the essay as well as relationships between parts of the visual structure. Brenda’s stunning visual structure could be lived in, walked on, journeyed through, much the way a good argument’s unfolding is often the very narrative of the writer’s bringing it into existence.

Category B: Structures that Metaphorize the Essay’s Argument

The structures I placed in Category B use material forms to create visual metaphors for the ideas in the students’ essays. Rather than giving physical shape to the generic containers of academic essay structure (introduction, thesis, body paragraphs, transitions) as the structures in Category A do, these models explore ways in which an essay’s argument itself—the very ideas the writer wishes to communicate—provides inspiration for a three-dimensional design. The students who approached the activity with structures placed in this category adhered most closely to Pericoli’s approach to the translation between verbal and visual texts in LabLitArch. The models in Category B show how the ideas held within the generic containers of academic essay structure mold and shape the containers themselves, and how form and content are imbricated.

Figure 5. Amanda’s Structure

“With the structure I built, you can see a lot of circular patterns. The idea of these patterns relate to both my essay structure and the ideas within my essay. The topic of the essay was relating technology and the impact of the connections it makes. When I think of connections, I think of circles, hence why I used circular edges. In my essay, I talked about experiences, interactions, memories, and connections. For each of my main ideas, I thought up ways to incorporate them into my infrastructure. With the word ‘experience,’ I thought of openness and being able to look out. Therefore, I added windows and had an open-like quality to my piece. For interactions, I thought about closeness and togetherness. With that, I constructed stairs that are close together that lead up to a black-hovering platform. This platform is essentially my thesis overall as it hovers over the structure. The connecting rods I have around the platform are the connecting elements, whether it be transitions, supporting evidence, or a part of my argument. As for the memories and connections, we are always looking back on memories and going back to them. This incorporates the circle idea further.”

Amanda writes that the circular patterns in her model communicate both “essay structure” and “the ideas within my essay.” She differentiates between structure, meaning “thesis,” “transitions,” and “supporting evidence,” and ideas, what the structures contain, but, true to her argument, she uses the circle to express the fluidity between structure and ideas. Her structure is composed of a series of circles because circles represent the idea of connectedness—form and content are inseparable. She wants, as she writes, to incorporate each of her main ideas into her infrastructure, or build an object that expresses her ideas out of the ideas themselves—I can think of no better invocation of Brown’s and Rivers’ rhetorical carpentry. The idea of openness assumes the form of windows, togetherness the form of stairs. Even more interesting is her way of translating thesis into a platform that “hovers” over the entire structure, and transitions as connecting rods. Even these generic essay elements are pulled into the integration between form and content, structure and ideas, material and verbal expression.

Figure 6. Adam’s Structure

“The spikes on my structure represent the aggression and harshness in my paper, starting off small and calmer, and culminating in large, menacing spikes. The house on the top represents what my paper is defending: human kindness.”

Amanda’s argument is all about connections—between people, between form and content, between experience and memory—and her structure expresses those connections in the form of circles. Adam’s structure and writing, however, revealed to him the disconnect in his essay between the point he wants to make and the tone by which he makes it. Adam writes that his essay evinces an “aggression” and “harshness,” represented by the spikes on the material structure. Indeed, having read his drafts, I can attest to the aggressive way the essay makes its argument, at the sentence level in Adam’s word choice and short, punchy sentence structure, and in the way the essay drives home supporting points and evidence, one after another, in quick succession. Adam’s realization that his defense of “human kindness” is at odds with the form it takes is reflected in the juxtaposition between the unwelcoming “spikes” and the welcoming figure of the house to which those spikes lead. Thus, an essay can be at odds with itself, even one in which the argument is sincere and its development well-executed. This incongruity can make us feel uneasy, as we do when viewing Adam’s structure, despite our interest in it.

Category C: Structures that Express the Writing Process

The structures I placed in the final category approached LabWritArch from a perspective I had entirely neglected to consider, and because of this, they were the most interesting to me as an instructor. Out of the twelve total structures produced in the course, only two fell into this category, and because they represented such a unique interpretation of the assignment, I’ve included them both here. Both of these students used their structures to express what they felt to be the process of turning raw ideas, intuitions, hunches, and emotional responses into an academic essay. In other words, these structures represent the process of writing itself—how thoughts are transformed into words, how feelings and emotions are channeled into or suppressed through the act of writing. These structures make manifest the struggle we ask our students to go through each time we ask them to write for us—for their college professors in an academic environment.

Figure 7. Liam’s Structure

“My model is composed of two main parts representing my internal thoughts and process I had when writing this essay. The small pillar in the garden shows my personal feelings on the given topic. The taller tower by the roads and in the paved square shows the argument presented in my final draft. My personal feelings on this topic are more nuanced and not as clearly formulated as my final draft. This is why the small pillar that represents it is in a garden. An unruly, more chaotic place. The argument in my essay is more aggressive and passionate about the topic simply because it provided for a better and more full-bodied essay. The tower is surrounded by a concrete public square because the argument is solid and orderly. The large wave of a roof connecting the tower and the pillar shows the writing process itself, connecting the two in their commonalities.”

In Liam’s structure, the writer’s “personal feelings on the given topic” are both separated from and joined with the “argument presented” in the final draft by the writing process. The alpha and omega of the writing process—the thoughts with which we begin and the argument fully formed—are shown to stand far apart. The pillar representing the writer’s initial thoughts is smaller because these thoughts are “not as clearly formulated” as the argument in the final draft. The initial thoughts, however, are “more nuanced” than the clear formulation they become. This small pillar stands in a garden, an “unruly” and “chaotic” place, but a fruitful, lush, verdant one, too. The final argument is “solid,” “orderly,” more imposing. It is allowed to stand in a “public square” made of “concrete” while the writer’s initial thoughts are not. The argument is created with a public in mind and according to the requirements of a public discourse.

I couldn’t tell if Liam chose to represent his initial thoughts as the smaller of the two pillars because he himself valued them less than the final argument, or if he was depicting a value judgment he felt was held by his academic readers. Liam’s structure reveals his understanding of the writing process as a journey from Edenic freedom to disciplined civilization—the torn felt meeting the orderly lines illustrates this splendidly. One gains authority and a public voice while losing something quieter and smaller, but something important.

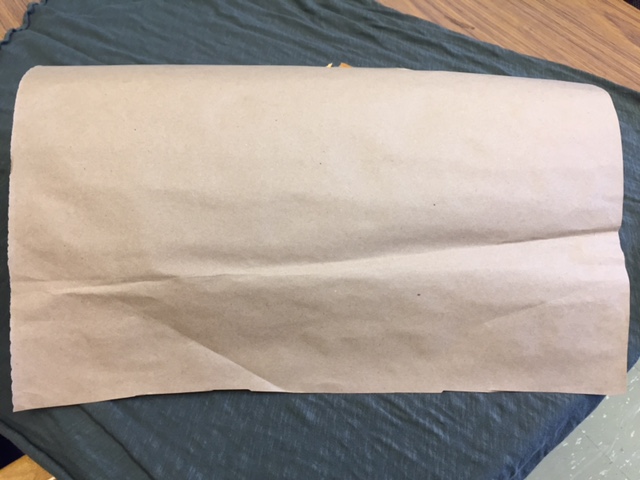

Figure 8. John’s Structure

“What my project represented was structure within chaos. What I mean by that is that all the small pieces were my ideas and thoughts. and then the diving bored was the process of writing them down in a clear way that everyone one would understand. hints why they was a judge panel, that represented how everyone would judge my work.”

Liam’s structure and writing express academic writing as loss—loss of what does not fit in, of what must be straightened out, solidified, and ordered. His understanding that what is “more aggressive and passionate” makes for “a better and more full-bodied essay” made me stop and think about the kinds of arguments I require in my courses. When I define what constitutes a good argument in my classes, what ideas, methods of argumentation, and voices do I leave out?

John’s structure and writing provide a poignant response to this question. Like Liam, John begins the writing process in a state of chaos, here depicted as a landscape of scattershot figures and shapes. These figures and shapes seem to be glued on at random, but as John writes, there is “structure” here, even “within chaos.” Perhaps that structure is not fully realized by the writer and thus not discernible by the reader, but there is order of a sort nonetheless. Reading this sentence of John’s writing made me appreciate that even the student drafts that seem to be composed of merely words on a page deserve an instructor’s respect for the mind learning to express itself.

John’s writing struck me most deeply, perhaps, of all the writings I received, because I read it as an emotional plea to be accepted through one’s writing into the world of academe. He expresses the writing process as one in which imperfections must be covered—represented by the brown butcher paper draped over the entire structure—in order to be “judged” favorably. He compares the process of presenting one’s ideas in the form of academic writing to a leap of faith into the deep end of the swimming pool. The act of writing down one’s ideas is represented by the figure of the diving board—fraught with danger, negative consequences, unpredictability. If writing is like diving, a writer can get submerged, can drown in the expectations he fails to meet.

Looking at John’s structure and reading his writing about it, I could not help thinking of David Bartholomae’s Inventing the University, which, when I read it for the first time as a graduate student, forced me to acknowledge the consequences of asking our students to learn to speak the language of the academy. They must learn, Bartholomae writes, “to speak as we do, to try on the peculiar ways of knowing, selecting, evaluating, reporting, concluding, and arguing that define the discourse of our community” (4); or, they must “carry off the bluff, since speaking and writing will most certainly be required long before the skill is ‘learned’” (5). I had had John in my basic writing course in a previous semester. I knew him as a student who struggled intensely with writing, but also with being accepted as a fully-fledged member of the educated ranks. Indeed, as Bartholomae warned us nearly thirty years ago, the academy’s gates are kept by its language, and the shibboleth is knowing how to use it.

LabWritArch could be one activity that helps first-year students develop that language by, counterintuitively, asking them to step back from the words and consider what the words do, how they shape and transmit critical inquiry and the freedom of thought such inquiry should make possible. Too often, first-year writing students focus on the restraint that words and sentences produced for school put on their everyday utterances, rather than the potential they bear for expressing new and profound ideas. As Pericoli says, LabLitArch “is a process of reduction.” If the “skin” of architecture is the “‘language’ of walls, ceilings and slabs,” which, once removed, leaves you with “sheer space,” in writing, “once you discard language itself, the actual words,” what’s left might be something like rigorous and rational thought—protean academic thinking—that can be formed from many materials and cross disciplinary boundaries.

Conclusion: Writing, Building, Design, and Transfer

Overall, my students enjoyed LabWritArch. After we finished the activity, I asked my students in an informal discussion during the following class session what they thought of the activity. One architecture major said that, being a first-year student in the program, he had not yet done any model-building or what he would consider “design work” in any of his actual architecture courses, so it was a welcome surprise that he was given the opportunity to flex his design muscles in a class where he least expected it. Several of the other architecture students concurred. Not everyone found LabWritArch to be a good use of class time, however. On an anonymous course evaluation at midsemester, a student wrote that he or she “did not get anything out of the activity.”

I found this comment insightful. I did not create or implement LabWritArch in order for students to “get” anything in particular out of it. It was not an activity by which I wanted to impart a specific piece of writing knowledge to them, such as the difference between adjectives and adverbs or how to place modifiers. I did not want to dictate what the students gained from the experience; in fact, I did not wish to force them to gain anything articulable at all in the immediate present. First and foremost, the activity gave students an opportunity to reflect on their written essays by seeing them in another form. By building models of their written work, students were asked to recognize and explain the rhetorical choices they made in that written work, and to explore how those choices might take shape in another medium. As Shipka says of her own classroom experiments, “students who explored other rhetorical and material potentials for their work were often able to account for what they did, why, and how, and this was something that students who continued to work in highly routinized ways were unwilling or unable to do” (“Negotiating” W345).

Secondly, the activity illustrated concrete connections between writing and design. It broadened students’ assumptions of what could and should be done in a writing classroom, and showed them that one’s capacity and skill in writing can be developed using many different modes and materials. It showed them that writing could be translated into, and reinterpreted with, other creations, and these creations could stand as objects in their own right while complementing their verbal and written work. Ultimately, whether they actually understood any of my intentions is not as important as the fact that the activity provided them an unexpected learning opportunity.

I hope that fellow writing instructors find in LabWritArch a reproducible and adaptable module that encourages their own students to see connections between writing and design. Although most of the students in my iteration of LabWritArch were architecture majors and came to the course with a prior interest in building models, the activity does not require any previous skill in model-building or designing. The students in my class produced sophisticated models and were able to draw upon the language they had acquired in their major courses to reflect upon them verbally. However, models of any degree of sophistication described with any words a student may choose can benefit his or her understanding of the purposeful design that goes into writing a thoughtful composition.

LabWritArch provides teacher-scholars a way to connect writing to design-related initiatives across the curriculum, especially at STEM and other non-liberal-arts colleges and universities where WPAs and instructors must make the case for writing’s place at the institution. For students that do not consider themselves “writers” or “good at writing,” creating the opportunity for them to conceptualize writing as a form of design can be appealing. Furthermore, the activity’s use of material objects to encourage students to explore a particular design concept—in this case, structure—concretizes the connections between writing and design, as well as between composition courses and courses in the students’ majors.

Finally, I would like to propose that LabWritArch suggests how design might contribute to the question of transfer in writing studies. Kathleen Yancey, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak sum up transfer’s scope of inquiry as “how we can support students’ transfer of knowledge and practice in writing; that is, how we can help students develop writing knowledge and practices that they can draw upon, use, and repurpose for new writing tasks in new settings” (2). To that end, the authors emphasize the need to help students develop the conceptual or theoretical knowledge underlying the tasks we ask them to complete: “we are coming to understand that if we want students to practice ‘better,’ in fields ranging from chemistry to history and even in medicine, we need to help them understand the theory explaining the practice, the logic underlying it, so that it makes sense to them” (4). Through reflection, the authors suggest, students should be asked to do what “we might call big-picture thinking, in which they consider how writing in one setting is both different from and similar to the writing in another, or where they theorize writing so as to create a framework for future writing situations” (4). Building this framework is essential to achieve what David Perkins and David Salomon call “high-road (or mindful) transfer involving knowledge abstracted and applied to another context” (qtd. in Yancey et al 7).

LabWritArch proposes that the task of transforming the structure of one’s own writing into a three-dimensional physical form develops both the capacity for creating a theory of form and for abstracting and applying that theory to many different contexts in many different disciplines. But LabWritArch’s emphasis on design sees writing as one among many ways to create insightful structural forms, opening up ways of pairing writing and making across the curriculum. While transfer in writing studies focuses on rhetorical concepts that make students better writers across the curriculum, LabWritArch can make writing, and specifically first-year composition, integral to initiatives that make students better creators across the curriculum. Matthew Newcomb has suggested that design can act as a “habit of mind” that fosters a disposition of “habituated situational creativity” that travels with students through all of their college courses (594-95). When we teach students to think about writing as a vehicle by which design can be explored and expressed, they will be better able to understand how first-year composition and other writing courses are relevant to any and every major or concentration. Framing writing as design helps students develop language, tools, and a mindset that transfers from one creating situation to another.

Instead of remaining focused on how we write across contexts, then, writing instructors and administrators might explore creating across contexts, with writing as one of those contexts. The primacy of writing would not be lost in such an initiative, as first-year composition is still commonly one of the first courses students take in college. With activities such as LabWritArch that feed into the broader goal of constructing generalizable concepts that travel with students, first-year composition can become the foundation for all courses of study that promote the theory and practice of purposeful creation.

Notes

-

Brown and Rivers’ term is fashioned after Ian Bogost’s notion of “philosophical carpentry,” which “entails making things that explain how things make their world. Like scientific experiments and engineering prototypes, the stuffs produced by carpentry are not mere accidents, waypoints on the way to something else. Instead, they are themselves earnest entries into a philosophical discourse” (Bogost 90-91). Bogost and other philosophers, including Graham Harman and Levi Bryant, are associated with object-oriented ontology, a branch of the philosophical movement of speculative realism (Reid, n.p.). (Return to text.)

-

Brown and Rivers, along with other scholars including Scot Barnett, Alex Reid, and David Sheridan, take an object-oriented approach to rhetorical analysis and/or the study of composition instruction. As part of writing studies’ turn to new materialism, object-oriented approaches investigate “objects existing in their own rights, and as such having relations and adventures with other objects regardless of whether these adventures are directly observable or accessible to human consciousness or perception” (Barnett n.p.). In its use of physically manipulative objects, LabWritArch possesses some attributes of object-oriented philosophy. My students’ material creations were formed first as representations of their verbal writing, but eventually took on something of a life of their own as they appeared, stage by stage, during the days of construction in the classroom, and then as finished products displayed and explicated during oral presentations. The models circulated the hallways, dorm rooms, and common areas on campus, and later, in photographs. Now, many of them have been collected and stored in my office, and in the quiet of my own work space, they remind me not only of the essays that inspired them, but strike me with their angles, edges, textures, and evidence of skilled craftsmanship and earnest effort.

However, my activity places the bulk of its emphasis on how physical objects used in the writing classroom aid students in their sense of how all texts—verbal, visual, aural, multimodal—are purposeful designs. My activity focuses on composition as design, rather than composition as object, although it does indeed use objects to make its point. The activity uses objects in a human-centered way, rather than proposing to shift our understanding of reality to center on the object. Thus, I frame this article from the perspective of reconceptualizing writing as design and how such an endeavor opens the writing course up to design initiatives across the curriculum, rather than from the perspective of new materialism. There are certainly fruitful connections to be made between design and object-oriented approaches for R/C. See, for example, Pflugfelder’s Rhetoric’s New Materialism, which also presents a helpful summary and taxonomy of various new materialist approaches to R/C (443-444).

LabWritArch is, at its most fundamental level, a classroom-based activity that focuses on what Steven Krause has called “‘words in a row’ kinds of writing skills.” It uses manipulative objects to help students reflect on the design of their written academic essays by putting to them the task of translating those designs into material, non-verbal form. I stand alongside Krause when he writes, in a review of Sheridan’s Fabricating Consent, that for at-risk students or those who “struggle mightily with some very basic, traditional, and unsexy writing skills,” we would do well to “focus first on those arguably boring and traditional elements of a writing course,” and “incorporate other elements of writing (e.g., 3D fabrication, visual rhetoric, audio, etc.) only as it relates to “the basics.” Students at STEM institutions, while not necessarily from at-risk populations, often do struggle with basic writing skills, and even more often, struggle with apathy and disinterest toward writing and the humanities. Thus, my activity aims to use “other elements of writing” to complement and aid the basics, while using those other elements to connect writing and writing courses to initiatives across a non-liberal-arts university. (Return to text.)

-

Rebecca L. Miner’s “Timeline Maps” assignment is another example of the innovation and creativity fostered by the use of physical manipulatives in the writing classroom. See Kitalong and Miner 47-54. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Barnett, Scot. Toward an Object-Oriented Rhetoric. Enculturation, vol. 7, 2010, n.p., http://enculturation.net/toward-an-object-oriented-rhetoric. Accessed 6 August 2018.

Bartholomae, David. Inventing the University. Journal of Basic Writing, vol. 5, no. 1, 1986, 4-23.

Bogost, Ian. Alien Phenomenology, or, What it’s Like to be a Thing. U of Minnesota P, 2012.

Brown, James J. and Nathaniel Rivers. Composing the Carpenter’s Workshop. O-Zone: A Journal of Object-Oriented Studies, vol. 1, 2014, pp. 27-36.

Buchanan, Richard. Design and the New Rhetoric: Productive Arts in the Philosophy of Culture. Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 34, no. 3, 2001, pp. 183-206.

Hecker, Linda. Walking, Tinkertoys, and Legos: Using Movement and Manipulatives to Help Students Write. The English Journal, vol. 86, no. 6, 1997, pp. 46-52.

Kitalong, Karla Saari and Rebecca L. Miner. Multimodal Composition Pedagogy Designed to Enhance Authors’ Personal Agency: Lessons from Non-academic and Academic Composing Environments. Computers and Composition vol. 46, 2017, pp. 39-55.

Krause, Steven D. On Sheridan’s ‘Fabricating Consent: Three-Dimensional Objects as Rhetorical Compositions.’ Blog. http://stevendkrause.com/2011/01/16/on-sheridans-fabricating-consent-three-dimensional-objects-as-rhetorical-compositions/. Accessed 6 August 2018.

Leverenz, Carrie S. Design Thinking and the Wicked Problem of Teaching Writing. Computers and Composition, vol. 33, no. 1, 2014, pp. 1-12.

Marback, Richard. Embracing Wicked Problems: The Turn to Design in Composition Studies. College Composition and Communication, vol. 61, no. 2, 2009, pp. 397-419.

Newcomb, Matthew. Sustainability as a Design Principle for Composition: Situational Creativity as a Habit of Mind. College Composition and Communication, vol. 63, no. 4, 2012, pp. 593-615.

Palmer, Judith, and Jan Thompson. First-Year English: Welcoming Different Learners to the Table. CEA Critic vol. 75, no. 3, 2013, pp. 293-302.

Pericoli, Matteo. LabLitArch: The Laboratory of Literary Architecture. LabLitArch. http://lablitarch.com. Accessed 18 Nov. 2017.

---. Writers as Architects. New York Times, 3 Aug 2013. https://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/author/matteo-pericoli/.

Pflugfelder, Ehren Helmut. Rhetoric’s New Materialism: From Micro-Rhetoric to Microbrew. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 45, no. 5, 2015, pp. 441-61.

Purdy, James P. What Can Design Thinking Offer Writing Studies? College Composition and Communication, vol. 65, no. 4, 2014, pp. 612-41.

Reid, Alex. Composing Objects: Prospects for a Digital Rhetoric. Enculturation, vol. 14, 2012, n.p., http://enculturation.net/composing-objects. Accessed 6 August 2018.

Sheridan, David M. Fabricating Consent: Three-Dimensional Objects as Rhetorical Compositions. Computers and Composition, vol. 27, no. 4, 2010, pp. 249-65.

Shipka, Jody. A Multimodal Task-Based Framework for Composing. College Composition and Communication, vol. 57, no. 2, 2005, pp. 277-306.

---. Negotiating Rhetorical, Material, Methodological, and Technological Difference: Evaluating Multimodal Designs. College Composition and Communication, vol. 61, no. 1, 2009, pp. W343-W366.

Sirc, Geoffrey. English Composition as a Happening. Utah State UP, 2002.

Taylor, Todd. Design, Delivery, and Narcolepsy. Delivering College Composition: The Fifth Canon, edited by Kathleen Blake Yancey, Boynton/Cook, 2006, pp. 127-40.

Wysocki, Anne Frances. Awaywithwords: On the Possibilities in Unavailable Designs. Computers and Composition, vol. 22, no. 1, 2005, pp. 55-62.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, et al. Writing across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State UP, 2014.

Building Structure and Thinking Design from Composition Forum 42 (Fall 2019)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/42/structure.php

© Copyright 2019 Vivian Y. Kao.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 42 table of contents.