Composition Forum 52, Fall 2023

http://compositionforum.com/issue/52/

Providing Peer Feedback as a Threshold Concept for Writing Transfer

Abstract: This article presents the results of an IRB-approved study investigating what learners self-identify about their writing-transfer learning in 3,404 reflections on providing peer feedback. Drawing on writing-transfer theory, results are analyzed according to what learners self-identify about writing transfer in the following three areas: writing-knowledge transfer; near- and far-writing transfer; and dispositions toward transfer. This article proposes foregrounding writing transfer from providing peer feedback by making the following questions explicit for learners in peer-feedback experiences: How might you become a better writer by providing peer feedback? What might you learn about writing from providing peer feedback?

Introduction

“If there’s a common thread in my students’ complaints about peer-review sessions, it’s that their classmates are usually too nice.”— David Gooblar, Why Students Hate Peer Review, March 1, 2017.

“My students always hate peer reviews by fellow students. They hate sharing their work. They hate reading one another’s work. The most common complaint I hear about peer review from students is when their peer says the paper was good, and then I comment on it only to say that it’s actually not good yet. They say it’s useless.”

— Rachel Wagner, Peer Review Reviewed, Inside Higher Ed, November 27, 2018.

Despite decades of research exploring best practices for and benefits of peer review, attitudes such as these persist among students. Questioning the value of peer review and focusing on perceived shortcomings of feedback received not only limits students’ writing growth but also underscores an all-too-often underdeveloped opportunity to “teach for transfer” (Perkins and Salomon) through a focus on providing peer feedback. This article proposes foregrounding writing transfer from providing peer feedback by making the following questions explicit in peer-feedback experiences: How might you become a better writer by providing peer feedback? What might you learn about writing from providing peer feedback?

The opportunity to explore these questions at unprecedented scale and learner heterogeneity emerged with the launch of the first-ever writing-based Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), “English Composition I” (EC) developed in partnership with Duke University and Coursera, and funded largely by a grant from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Comer, English Composition).{1} EC’s initial iteration ran 18 March-10 June 2013, enrolling 82,820 learners from 187 countries. Peer feedback (formative and evaluative) was central to EC’s design even with vast learner heterogeneity across age, education, writing experience, and written English proficiency.{2} Mitigating these challenges, EC adopted, in consultation with writing-assessment expert Ed White, a multipronged approach grounded in structured peer feedback, self-reflection, and an explicit, sustained emphasis on providing peer feedback as a site for writing transfer.

This article presents the results of an IRB-approved study investigating what EC learners self-identify about their writing-transfer learning in 3,404 reflections on providing peer feedback. While EC may constitute a specific pedagogical context, writing transfer resulting from providing peer feedback has wide application amidst burgeoning diversity in the contexts of post-secondary populations, increasingly flexible, hybrid teaching modalities, and growing attention to the complexities of writing transfer.

Literature Review

Writing transfer, defined in the Elon Statement on Writing Transfer, is “the phenomenon in which new and unfamiliar writing tasks are approached through the application, remixing or integration of previous knowledge, skills, strategies, and dispositions” (n.p.). Writing-studies scholars have built on David Perkins and Gavriel Salomon’s foundational research on learning transfer to explore many aspects of writing transfer, from pedagogical imperatives (Comer, Writing; Downs and Wardle) and genre awareness (Rounsaville; Goldschmidt), to metacognition (Beaufort, College Writing), student agency (Nowacek), and dispositions and emotions (Driscoll and Wells).

One key area informing our knowledge about writing transfer involves threshold concepts (Adler-Kassner, et al.), which operate as “portal[s], opening up a… transformed way of understanding” (Meyer and Land 3). In Naming What We Know, editors Elizabeth Wardle and Linda Adler-Kassner and contributors draw on Meyer and Land’s characteristics of threshold concepts—transformative, irreversible, integrative, and counterintuitive (Adler-Kassner and Wardle 2)—to identify five key threshold concepts for writing studies. Operating as both “boundary objects” and as a “heuristic” (Yancey, Coming to Terms, xix), these five threshold concepts include thirty-seven sub-concepts, mapping key areas of writing studies from ethics and identities to form and habituated practice. While Wardle and Adler-Kassner emphasize that their list of threshold concepts “do not and cannot represent the full set of threshold concepts” (8) for writing studies, key writing practices such as revision, reflection, and metacognition feature prominently, especially throughout “Concept 4: All Writers Have More to Learn.” Peer feedback, however, is notably absent, perhaps in part because faculty and students often have mixed perceptions of and experiences with this practice since it is often framed with an overemphasis on feedback received rather than also considering the transfer-based opportunities related to feedback provided.

Despite decades-long awareness that providing peer feedback helps students define tasks, diagnose problems, and develop revision plans (Hayes and Flower; Hayes et al.), along with centuries-long wisdom about the writerly benefits of reading,{3} the preponderance of peer-feedback research to date largely focuses on the impact of peer-feedback received. Moreover, although scholars recognize that writing transfer involves a complex web of remixing, transformation, and repurposing (Yancey, Writing), very little research has explored providing peer feedback through a theoretical frame of writing transfer.

Peer feedback itself is a widely researched and staple component of writing pedagogy, borne in the 1960s and 1970s when James Moffett and Betty Wagner, and Donald Murray advocated for writing workshops, Carol Sager documented peer feedback in a sixth-grade writing class, and Ken Bruffee defined writing teachers as organizers of knowledge instead of content deliverers (Bruffee, Collaborative). Over the ensuing decades, researchers have identified many benefits of peer-feedback received: greater understandability and accessibility than teacher feedback (Topping, Colleges and Universities), more instances for and diversity of feedback (Cho and MacArthur, Student Revision and Learning by Reviewing; Cho, Cho, et al.), and increased sensitization to multiple perspectives (Cho and MacArthur, Learning by Reviewing). Done well, peer feedback has been shown to be as, if not more, effective than instructor feedback (Topping, Trends; Cho, Schunn, et al.; Cho and MacArthur, Learning by Reviewing).

Researchers have also identified that peer-feedback processes enhance valuable undergraduate soft skills, such as self-regulation, independent learning, time management, anxiety reduction, and social networking (Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick; Boud and Molloy; Chaktsiris and Southworth). Peer feedback in the form of evaluative peer assessment has also been well-researched, showing that, in certain contexts and with proper training, it can be as reliable as instructor assessment (Comer and White; Falchikov and Goldfinch; Kulkarni et al.).

A smaller body of research has identified writing-related gains from providing peer feedback, often within a particular disciplinary context or learner demographic. In STEM ([science, technology, engineering, mathematics)] contexts, for instance, students’ writing improves more through providing than receiving comments (Cho and MacArthur, “Learning by Reviewing”; Cho and Cho). In L2 contexts, providing peer feedback advances confidence (Min), self-assessment skills (Lundstrom and Baker), and zones of proximal development (ZPD) (Lundstrom and Baker; De Guerrero and Villamil). Providing peer feedback also enhances graduate-level dissertation-writing skills and confidence (Larcombe et al.; Aitchison; Maher et al.). Writing-center research offers perhaps the most robust scholarship about providing peer feedback, showing that tutors increase capacities in such areas as writing, critical thinking, empathy, awareness, analytical power, confidence, communication, self-assessment, autonomous learning, collaborative education, and understanding of assessment standards (DeFeo and Caparas; Hughes et al.; Bruffee, What Being and Brooklyn Plan; Marcus; Graner; Roscoe and Chi).

While such research on peer-feedback provided may implicitly signal writing transfer, hardly any of these studies explicitly draw on writing-transfer theory and none has yet done so within the context of first-year writing. Some research about peer-feedback provided addresses learning transfer, such as Melissa Patchan and Christian Schunn’s study from an introductory psychology course that uses Edward Thorndike’s Identical Elements Theory of Learning Transfer to analyze peer-feedback provided, finding that lower-skilled reviewers offer more praise than higher-skilled reviewers. Similarly, David Nicol, Avril Thomson, and Caroline Breslin draw on learning-transfer theory to explore peer-feedback provided in an introductory engineering course, showing that providing peer feedback renders gains in evaluative judgment, understanding assessment criteria, and self-directed learning (Nicol et al.). Perhaps the most expansive work to date conjoining writing-transfer theory and peer-feedback provided is Dana Driscoll and Bonnie Devet’s edited collection about writing-center tutors, wherein they explore writing-transfer theory as it relates to tutors’ feedback, professional development, and approaches to collaboration.

Building on such prior research, this article explores at unprecedented scale and learner heterogeneity what learners in the context of first-year writing self-identify about their writing-transfer learning from providing peer feedback.

Methods

Research Question

What do learners self-identify about their writing-transfer learning from providing peer feedback?

Research Context

EC, an introductory college-level writing MOOC, was launched in March 2013 and initially ran for twelve weeks. The first iteration, from which this study’s data were collected, enrolled 82,820 learners from around the world.{4}

EC’s instructional design includes seventy-seven interactive videos on writing and four major writing projects (see Appendix A): Critical Review of Daniel Coyle’s “The Sweet Spot”; Image Analysis; Case Study; Op-Ed. EC learners self-select one area of inquiry to explore across all four writing projects (e.g., climate change, social justice, architecture, parenting).

Because EC’s large enrollment precluded instructor feedback for each learner, course design relied on a multipronged approach to structured peer feedback (Brown et al; H. Li et al.; Topping, Peers as a Source and Learning by Judging), consisting of sample instructor feedback,{5} anonymous formative peer-feedback rubrics for drafts, and six-point anonymous peer-evaluation rubrics (see Appendix A).{6} Peer feedback was a sustained and central element of the course, as EC asked each learner to provide twenty-five peer feedbacks across the course (three rounds of peer feedback for drafts of the first three writing projects and four rounds of peer feedback for each of the four writing projects’ near-final versions).

EC’s pedagogy is grounded on writing transfer (Nowacek; Price et al.; Nicol et al.) and self-reflection (Sadler; Nicol; Carless et al.; Yancey, Reflection), emphasizing explicitly in the following instructional materials the potential for writing transfer from providing peer feedback (see Appendix A for fuller details):

Instructional Video about Peer Feedback (Week 3, “Responding towards Revision”)

EC lead instructor emphasizes how she becomes a better writer by responding to student writing and by exchanging drafts-in-progress with colleagues.Peer-Feedback and Peer-Evaluation Rubric Frame

The following sentence appeared at the top of each peer-feedback and peer-evaluation rubric, a total of twenty-five times across the course:{7} “***Reading and responding to other people’s writing makes you a better writer.***”

Self-Reflection Question on Peer-Feedback Rubrics for Drafts

“What did you learn about your own writing/your own project based on responding to this writer’s project?”Self-Reflection Question on Peer-Evaluation Rubrics for Final Versions

“What did you learn about your own writing based on reading and evaluating this writer's project?”Post-Project Self-Reflections

The following sentence appeared as part of a larger prompt in post-project self-reflections after each of the first three writing projects: “Having evaluated other writers’ projects and having received feedback on your own writing, please write a brief reflection on what you have learned about your strengths and areas for growth as a writer.”

End-of-Course Self-Reflection

The prompt invited learners to consider all their work in the course, including “feedback to and from colleagues” to compose a self-reflective, writing-portfolio cover letter about their growth as writers.

Study Participants

When learners enrolled in the March 2013 iteration of EC, they had the opportunity to also enroll voluntarily in an IRB-approved study. Of those who enrolled in the study, data were collected from a sample set of 250 learners, selected at random from a pool of 315 learners who had enrolled in the study and completed the course.{8} The dataset for this study consists of a further random subset of these 250 learners—learners 1-150—since the dataset from this subset was extensive enough to presumably yield generative insights and conclusions.

Data Collection

The data in this study are a portion of a larger dataset collected for EC research. Staff in Duke University’s Learning Innovation (then called the Center for Instructional Technology) collected the 250 learners’ writing projects (drafts and revisions), and the peer feedback/evaluation rubrics each learner had provided to peers, by downloading the material from the EC site, deidentifying it, discarding email addresses and names, and adding numerical identifiers 1-250. Deidentified data were placed in folders on a Sakai site (Duke University’s Learning Management System) created specifically for the IRB-approved research, labeled by learner number and writing project.

The data for this study consist of the 3,404 responses (see Table 1) learners 1-150 gave to the following open-ended questions that appeared as, respectively, the last question on each peer-feedback rubric for drafts and the last question on each peer-evaluation rubric for final versions:

“What did you learn about your own writing/your own project based on responding to this writer’s project?”

“What did you learn about your own writing based on reading and evaluating this writer’s project?”

Table 1. Study Dataset, Learners 1-150.

Writing Project |

Stage of Writing Project |

Learner Files |

# of Learner Responses to the Rubric Question about Potential Writing Transfer from Providing Formative Peer Feedback |

# of Learner Responses to the Rubric Question about Potential Writing Transfer from Providing Peer Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project 1: Critical Analysis | Draft | 146 | 464 | |

| Final Version | 140 | 571 | ||

| Project 2: Visual Analysis | Draft | 143 | 433 | |

| Final Version | 141 | 575 | ||

| Project 3: Case Study | Draft | 135 | 393 | |

| Final Version | 136 | 539 | ||

| Project 4: Op-Ed | Final Version | 122 | 429 | |

| TOTALS: | 963 | 1290 | 968 | |

| Total Learner Responses: | 3,404 |

Data-Analysis Methods

To analyze the 3,404 responses, Sakai site data were imported into NVivo, a qualitative data-analysis software, creating files identified by learner number and the writing project associated with the learners’ rubric responses about providing peer feedback. Data-analysis methods consist of qualitative and quantitative content analysis, using directed content analysis with a structured approach to coding (Auerbach and Silverstein; Weber; Hickey and Kipping; Potter and Levine-Donnerstein).

Coding was iterative (Smagorinsky). The codebook (see Appendix B) was initially developed using codebooks developed for previous EC research,{9} and then was adjusted and refined throughout the process using writing-transfer theory and as warranted by the data. A team of four, consisting of the lead researcher and three graduate-student research assistants conducted trial coding with two learners’ data (34 responses), and then met to review the coding agreement and adjust and refine the codebook. This team continued coding for a brief period, with periodic meetings to refine coding agreement and codebook, but after a pause in the research, the lead researcher then coded the complete dataset (re-coding the previously coded data as well), again adjusting the codebook as warranted by the data and writing-transfer theory.

When a response exhibited a code, the entire response was coded to that code (e.g., a response referencing argument three times was coded only once to argument). References in the “length” categories were only coded to one option (e.g., number of words in a response), but within the other main code categories, references were coded to multiple sub-codes if warranted (e.g., a response referencing argument and evidence was coded to argument and evidence).

After manually coding the data in NVivo, the lead researcher reviewed the code counts and qualitative data in each code for coding accuracy, and then performed selected keyword-based automatic coding (see Appendix B), reviewing auto-code results to eliminate errors and multiple coding within one response, and then merging these results with the manually coded results.

Data were analyzed by the lead researcher using NVivo coding queries and cross-tabulation, with quantitative data exported into Excel spreadsheets for further quantitative analysis and/or to create charts and tables.

Study Limitations

Since EC explicitly emphasized potential writing transfer from providing peer feedback, the two peer-feedback rubric questions from which the data are drawn were phrased suggestively, implying that potential writing transfer existed. Still, learners could, and sometimes did, indicate in their responses that they had not identified any writing transfer from a particular instance of providing peer feedback (e.g., “I don’t know” or “No comments”). Another study limitation is that the data are self-reported by learners and have not been correlated to learner performance. A third limitation is that the study fuses formative and evaluative peer feedback within the research question; a different study design would be needed to compare what students identify about writing transfer from providing peer formative feedback and peer evaluative feedback. A fourth limitation is that all study participants completed EC, which could make their responses about writing-transfer learning less representative of broader EC learners.{10} A fifth limitation is the MOOC context itself, which necessitated anonymous peer feedback and limited the opportunity for a dialogic approach to feedback, as well as shaped learner perspectives on peer feedback.

A final study limitation involves repetitive responses: 257 of the 3,404 responses (8.5% of all responses, occurring across 55 learners) showed a learner using exactly the same words in their response about writing transfer from providing peer feedback for two or more peers in the same project cycle. For example, one learner wrote “My writing should be more complex” to two of four peers as the response to the rubric question about what they learned from reading and evaluating their peer’s Project 1 final version. Without being able to discern learner intent—sustained attention to a particular aspect of writing or disengaged copy/paste—repetitive responses were retained and coded in the codebook, but also tracked through the “Repetitive” node.

Results & Analysis

The results below discuss what learners self-identify across 3,404 responses about their writing-transfer learning from providing peer feedback, addressing three primary areas of writing transfer: 1. writing-knowledge transfer; 2. near and far writing transfer; and 3. dispositions toward transfer. In this Results & Analysis section, the term “response” refers to a learner’s response about writing transfer from providing peer feedback to one peer; the term “reference” refers to when a learner’s response exhibited a particular code (e.g., audience, joy, frustration).

1. Writing-Knowledge Transfer from Providing Peer Feedback

A key area of writing-transfer research involves understanding what writing knowledge writers transfer. Thomas Reigstad and Donald McAndrew’s differentiation between higher-order concerns (HOCs) and lower-order concerns (LOCs) has been valuable for writing-transfer research in that HOCs offer greater potential for longer-term writing growth (Cross and Catchings; Tinberg). Similarly, HOCs optimize peer-feedback received (Rahimi; Min; Gielen and De Wever). Anne Beaufort’s five overlapping domains of writing knowledge in College Writing and Beyond also offer a powerful taxonomy for writing knowledge transfer: writing process knowledge; rhetorical knowledge; genre knowledge; discourse community knowledge; and content knowledge.

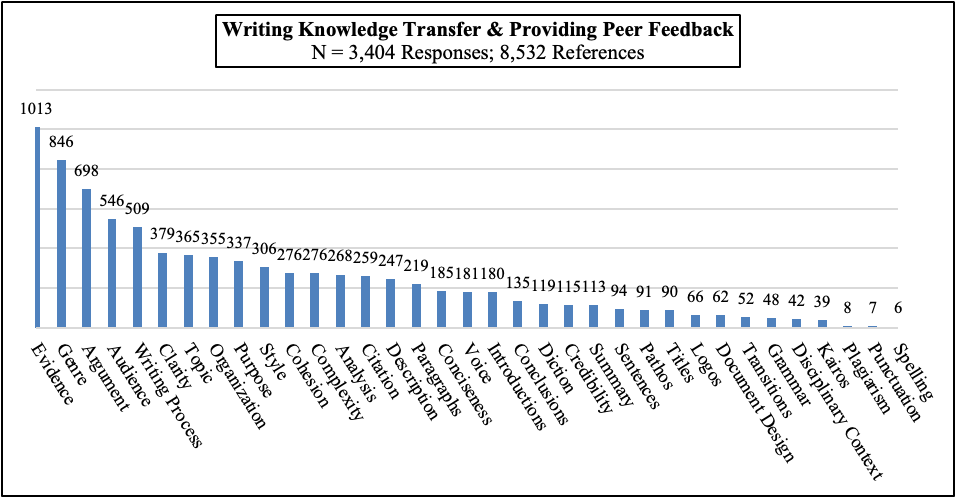

Figure 1 shows that learners identified writing knowledge across these five domains as they reflected on writing transfer from providing peer feedback, focusing with overwhelming frequency on HOCs compared to LOCs. The five most frequent writing-knowledge references, accounting altogether for 42.33% of writing-knowledge references, are all HOCs: evidence, genre, argument, audience, and writing process. HOCs of organization, topic, and purpose also featured strongly, comprising an additional 12.39% of all writing-knowledge references. By contrast, LOCs of grammar, spelling, and punctuation together account for less than one percent of all writing-knowledge references (0.71%). Clearly, emphasizing writing transfer through reflections on providing peer feedback offers a strong mechanism for transfer-based thinking around HOCs.

Figure 1. Writing Knowledge Transfer & Providing Peer Feedback.

The 1,013 references coded to evidence address matters ranging from quantity and purpose—I should use more references in my article - it helps to prove what we say and make it more believable; The importance of providing supporting evidence to all claims.—to credibility, e.g., A text that relies mostly on Wikipedia in its citations can seem incomplete, and strategies for integrating evidence: I will learn how to paraphrase others' work better.

The degree to which learners considered evidence as a HOC is also apparent in that citation references (direct mention of citation style and formatting) were a separate category, consisting of only 259 references as opposed to the 1,013 evidence references. Even within citation, though, learners were likely to use a HOC approach as 75% of the citation references (195/259) were coded for both evidence and citation, e.g., This project helped me appreciate how writers use evidence to support their arguments and gave me a better understanding of formatting and using citation in my writing.

Genre, the second most frequently coded area of writing knowledge, is a key indicator of writing growth and writing transfer (Devitt; Rounsaville; Rounsaville et al.; Wardle; Robertson et al.; Driscoll et al.). In Genre Knowledge and Writing Development, Driscoll et al., argue that as writers grow, they move from generalized genre knowledge, often focused on conventions, towards more nuanced understanding of genres, and then toward genre awareness, which includes awareness of the sociocultural activity systems such as audience and purpose that inform writing across and within varying contexts.

The 846 genre-transfer references from providing peer feedback demonstrate this range of writing development. Some references reflect earlier stages of generalized genre knowledge, e.g., make sure to understand what Op-ed writing involves, or exhibit a focus on genre conventions: Academic writing is all about following certain conventions. It is important to look at sample drafts in order to get an idea of the style of writing required. Others demonstrate more nuanced genre knowledge, such as the following insights about subject matter for, respectively, op-eds—I could have chosen a topic which would be more interesting for broader public [sic]—and case studies: I have learnt that a case study needs to move beyond a personal account. No matter how interesting and inspiring a personal account is, when it is restricted to one testimony it lacks academic authority and credibility.

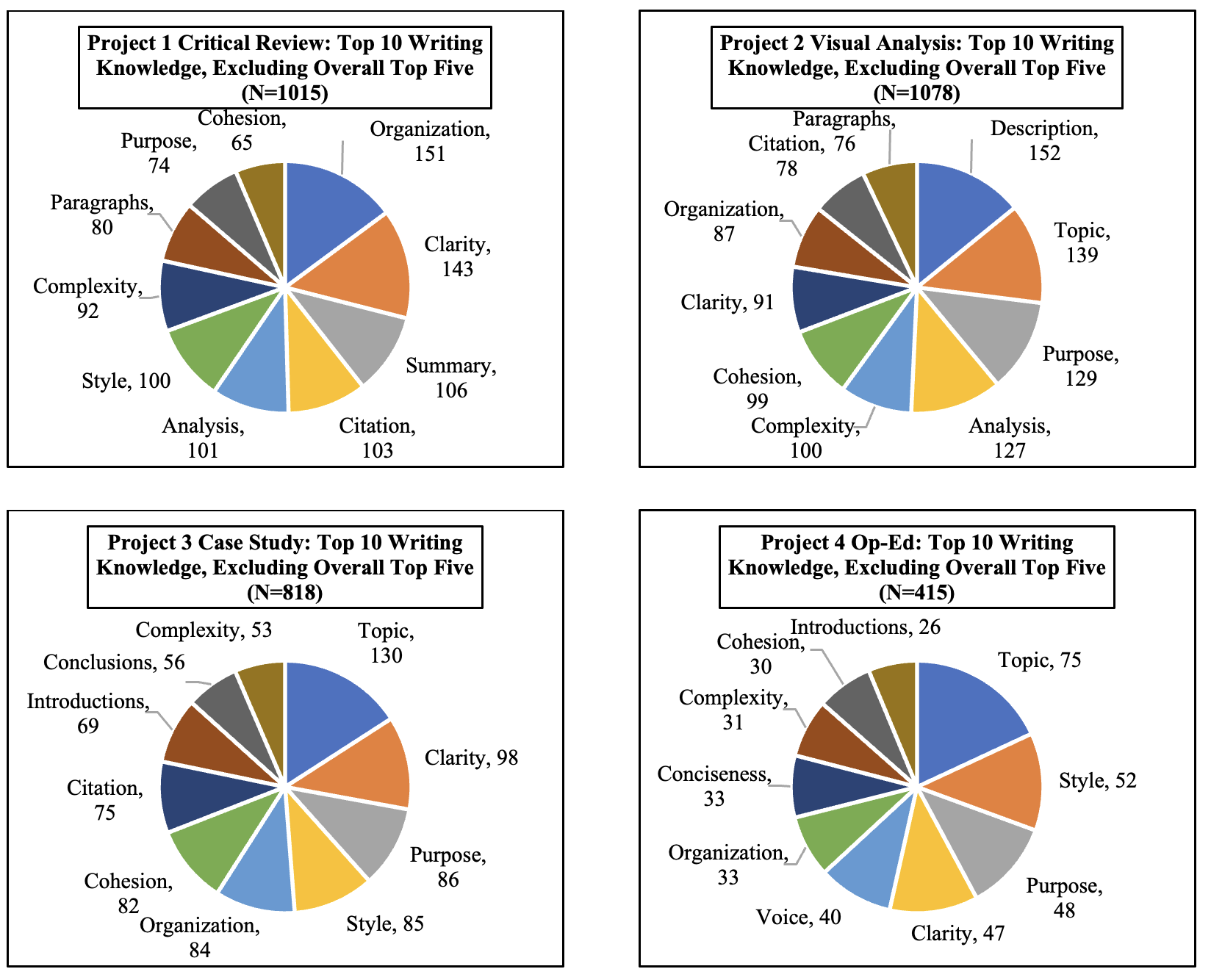

The distributions across writing knowledge for each writing project further demonstrate learners focusing on more nuanced genre knowledge as writing transfer. Figure 2 shows the ten most frequent areas of writing knowledge per project, excluding the top five overall (evidence, argument, genre, audience, and writing process).

Figure 2. Top 10 Writing Knowledge References per Project, Excluding Overall Top Five.

As Figure 2 shows, learners shifted writing-knowledge references across different writing projects, focusing on elements central to the project genre and thereby demonstrating that reflecting on writing transfer from providing peer feedback enables learners to deepen genre awareness. For instance, references such as summary and analysis feature strongly in the critical review, description and analysis in visual analysis, topic and organization in case study, and voice and conciseness in op-ed. Such correlations reveal students engaging with genre awareness throughout the course as a key area of writing transfer made visible through providing peer feedback.

Other genre references demonstrate more advanced genre awareness, such as rhetorical context: I need to focus on my personal voice and approach when writing an op-ed. Some learners demonstrated growth toward genre awareness across the course. Table 2 shows a subset of one learner’s responses related to genre.

Table 2. Learner 109: Genre Knowledge across the Course.

|

Writing Project Peer Feedback |

Learner 109: Genre Awareness and Potential Writing/Learning Transfer |

|---|---|

| Project 1 Draft | I am continuing to understand the genre better as I read more student examples. |

| Project 2 Draft | There is a wide variety of images to choose from, and each will inspire a very different essay. |

| Project 3 Draft | I'm not the only one struggling with the genre itself, and I want to revise the questions that I have in the introduction of my essay and use more research. |

| Project 4 Final | I am scared to use a non-academic voice, since that is the voice that I honed in school and in my career. |

As Table 2 shows, at the beginning of EC, the learner writes in general terms about genre, demonstrating interest in genre conventions. Then the learner moves in Projects 2 and 3 toward more nuanced genre knowledge by thinking about how image choice impacts visual analysis and the role of introductions and research in a case study. By Project 4, the learner again demonstrates nuanced genre knowledge about op-eds with the reference to personal voice, but moves toward genre awareness with a meta-cognitive reflection on rhetorical context, considering their own relationship with non-academic voice.

Argument was the third most frequent area of writing knowledge; these 698 references often overlapped with other HOC writing knowledge, such as organization and audience, e.g., The organisation of ideas need [sic] to be structured so that the reader can follow the argument, or evidence: Signposts assist the reader in following the author's argument. Table 3 shows the twelve most frequently referenced aspects of writing knowledge coded alongside argument, demonstrating that learners considered argument alongside all five of Beaufort’s domains of writing knowledge:

Table 3. Aspects of Writing Knowledge Co-Referenced with Argument.

| Writing Knowledge | Argument Co-References |

|---|---|

| Evidence | 263 |

| Genre | 191 |

| Audience | 98 |

| Clarity | 93 |

| Cohesion | 93 |

| Complexity | 81 |

| Analysis | 69 |

| Organization | 65 |

| Writing Process | 60 |

| Purpose | 57 |

| Citation | 50 |

| Topic/Subject | 45 |

The following response, for instance, demonstrates overlap between argument with the domains of writing-process knowledge, rhetorical knowledge, and content knowledge: Finding a good idea for a compelling argument is one thing, to strengthen the argument and make it more solid is hard work. I don't want to just hint at it, I want to fully flesh it out and make my argument as powerfully compelling as I can.

The 546 audience references suggest that EC’s explicit focus on writing transfer from providing peer feedback positioned peers as integral, authentic readers, e.g., Thoughtful, and a paper that provokes the reader to think more. Thank you for sharing. Audience references also explored what readers value, e.g., I enjoy reading work from good writers, especially when their topics pique my interest, and how aspects of writing knowledge impact readers, such as citation, e.g., If reference material is not correctly cited, that makes it difficult for the reader to verify the facts that are claimed, or background information, e.g., I should have given more information about Coyle's work in case people who read my article didn't read his work.

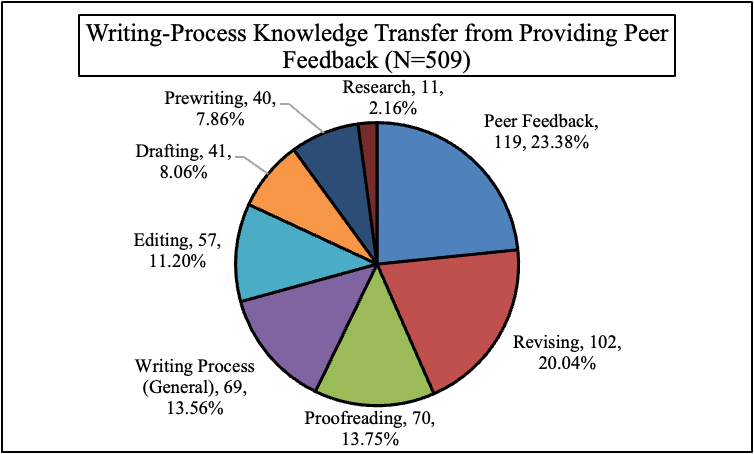

Writing-process transfer had the fifth highest frequency and is an area of writing knowledge particularly central to writing transfer (Beaufort, Real World and College Writing; Whicker). Figure 3 shows these 509 writing-process transfer references distributed across seven sub-categories:

Figure 3. Writing Process Transfer from Providing Peer Feedback.

Given that the questions for this study asked about writing transfer from providing peer feedback, it is not surprising that the majority of writing-process references (23.38%) addressed peer feedback. Here, learners reflected on the value of providing peer feedback, e.g., I have learned that as many peer's [sic] review we make, the better will be our final submission, and on attending to feedback received: That is important to pay attention to feedback. References to revision transfer (20.04%) from providing peer feedback addressed revision plans for drafts-in-progress, e.g., I need to re-examine my paper and see how to better integrate arguments, revision strategies, e.g., I've found the course's suggestion of reverse outlining is very helpful for me, and the value of revision itself: I was reminded of the importance of rewriting to make sure that my central thought is at the heart of my writing.

Figure 3 also shows that learners were far more likely to focus on HOC aspects of the writing process as opposed to LOCs. For instance, learners often referenced the time and effort needed for the writing process: I understand that to be a good writer one must practice deeply. There will be many drafts and revisions until the writer achieves his or her goal. By contrast, elements of the writing process associated with LOCs, namely editing, e.g., Read your work as many times as you can (for the grammar and sentence construction purposes), and proofreading, e.g., Double check work for little typo errors, accounted for, respectively, 11.20% and 13.75% of all writing-process references. Together, these two LOC elements of the writing process comprise only 24.95% of all writing-process references. This again demonstrates that reflection from providing peer feedback can meaningfully guide learners toward writing transfer focused on HOCs.

While topic references appeared with slightly less frequency than clarity, they also demonstrate learners reflecting on how providing peer feedback engenders transfer-based thinking around the domain of rhetorical knowledge. Learners reflected on topic selection, e.g., I learned about the importance of choosing a good image in an Image Analysis essay. (Duh, right?) This writer chose well, and it helped her essay; nothing felt forced like it did in my own essay, and topic boundaries: Don’t generalize… dive deep into a single critical aspect of the topic. Topic intersected with other areas of rhetorical knowledge 146 times, as Table 4 shows.

Table 4. Topic Co-References.

| Rhetorical Knowledge | Topic Co-References |

|---|---|

| Audience | 61 |

| Purpose | 45 |

| Kairos | 14 |

| Pathos | 11 |

| Credibility | 10 |

| Logos | 5 |

Here, learners often demonstrated considerations about subject in conjunction with Lloyd Bitzer’s notion of exigency: I learnt that you can write a very interesting article, but if you don't meet the task objectives then you have not done well.

While addressing every area of writing knowledge learners referenced would be beyond the scope of this article, it is evident that reflecting on writing transfer from providing peer feedback prompts a wide range of reflection on writing knowledge, predominately focused around HOCs.

2. Near and Far Writing Transfer from Providing Peer Feedback

Understanding what learners self-identify about their writing-transfer learning from providing peer feedback necessitates exploring what they articulate about writing knowledge but also their indications of how and where they envision transferring this writing knowledge. Perkins and Salomon offer a framework for learning transfer grounded on proximity: near transfer, “when knowledge or skill is used in situations very like the initial context of learning,” and far transfer, “when people make connections to contexts that intuitively seem vastly different from the context of learning” (202). With writing, David Russell’s “activity systems” help demonstrate that writers must use near- and far-writing transfer to navigate complex, dynamic writing practices, forms, and conventions across varied writing occasions.

Writing transfer research also acknowledges, however, that writers sometimes reject transfer altogether. “Transfer denial” (Jarratt, et al.) refers to occasions when learners “resist the idea of transfer” (Robertson, et al.), perhaps due to dispositions and identities (Wardle; Driscoll and Wells) or when faced with a particular writing context.

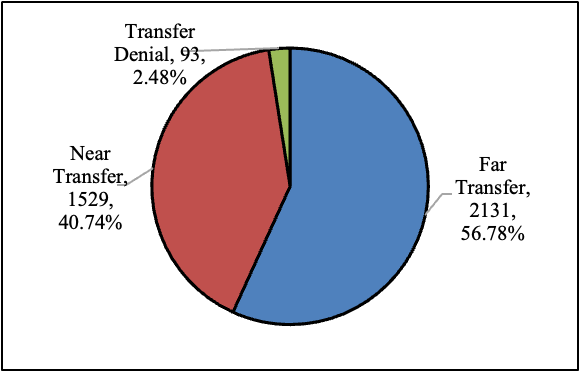

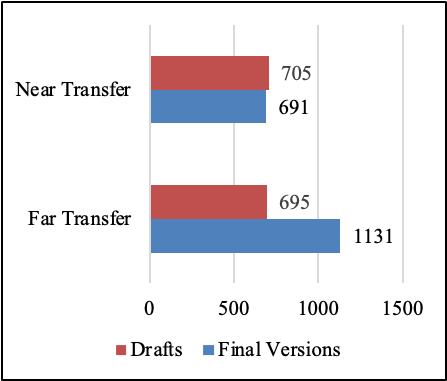

Figure 4 shows the 3,404 responses coded according to these types of writing transfer, demonstrating that providing peer feedback yielded more far-transfer (56.78%) than near-transfer (40.74%) references, and that transfer denial occurred at a very small margin (2.48%).{11}

Figure 4. Near and Far Writing Transfer from Providing Peer Feedback (N=3,404 Responses; 3,753 References).

The far-transfer responses reflect what Perkins and Salomon label high-road transfer, which requires “mindful abstraction of principles,” and low-road transfer, which involves “extensively practiced (near automaticity) skills” (Elon). In far-transfer, high-road references, learners suggested that providing peer feedback encouraged, for example, rhetorical awareness around how the “type of project” impacts writing choices, e.g., I have learnt that it is necessary to analyze what type of project I want to develop and what is the intended audience. What the central communication element is and select the best strategies to attain it. Far-transfer, high-road references also addressed the value of multiple perspectives in writing, e.g., It is important to look at many different sides … when writing, and writers’ relationships with what they are writing about, as in the following example where a learner thinks about the role of a writer’s humility and respect across different writing projects: I saw deep humility … I will take this humility and respect for the object of my study in project 3.

Far-transfer, low-road responses focused on how providing peer feedback foregrounded more automatic writing practices, such as proofreading strategies, e.g., I learnt the importance of reading aloud and proofreading my work before submission, and outlining: I have learned how important it is to plot out an essay in order to be able to fill in the salient points that need to be made.

Some far-transfer responses demonstrated that providing peer feedback fostered metacognition about far-transfer itself: e.g., A painting can be used … in a completely different domain, like research science; I learned that I really should try yoga someday since it can relieve my stress (physical and mental). On the long run [sic], it will probably make me a better writer. These examples suggest that reflecting on writing transfer from providing peer feedback can activate far-transfer habits of mind, with potential spread of effect to peers when such reflections are made visible between peers, as was the case in EC.

Some far-transfer responses also portend negative transfer (Osman) or frustrated transfer (Nowacek), whereby writers’ prior knowledge or assumptions work against success in a new writing occasion. For example, one learner wrote, to keep the reader engaged in our essay, we have to use some informal writing. While informal writing might be appropriate in some contexts, this learner seems to be assuming it would be effective in all writing occasions. This suggests that asking learners to reflect on writing transfer from providing peer feedback might offer moments for faculty to intervene, if needed, to reduce the possibility of future negative transfer.

Near-transfer responses tended to focus on one of three areas: genre-based knowledge (e.g., It's definitely good to stick with recent news with Op-Eds), writing knowledge more automatic in nature (e.g., I have to get more specific and look at the instructions a bit better myself), or the feedbackers’ own drafts-in-progress, be it high-road—Asking you to provide the evidence on that claim about genetics made me realize that I have made similar assumptions in my own draft that I will need to correct—or low-road: I must have written a recommendation of the book for people, at the last line.

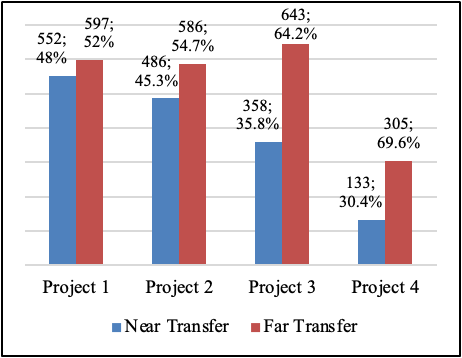

Because far transfer and high-road transfer activate more complex cognitive capacities and have wider applicability than near transfer and low-road transfer, writing-transfer research often accords higher value to far transfer. Rebecca Nowacek, for example, offers a continuum where writers advance from detection to integration, moving from near and low toward far and high. Figures 5{12} and 6 show that, with sustained opportunities to reflect on writing transfer from providing peer feedback, learners became more inclined toward far transfer.

Figure 5. Near and Far Writing Transfer from Providing Peer Feedback on Drafts vs. Final Versions (Writing Projects 1-3) N=2,976 Responses; 3,222 References

Figure 6. Near Transfer to Far Transfer Development across EC from Providing Peer Feedback (N=3,404 Responses; 3,660 References).

Figure 5 shows learners almost doubly inclined toward far transfer after providing peer feedback on final versions (1,131 references) than drafts (695 references). Figure 6 shows the percentage of far-transfer responses increased with every project, particularly during the second half of EC, where 67% of responses were far transfer (53% of responses were far transfer in the first half of EC). Together, this increased movement toward far writing transfer across drafts and revisions, and across EC, suggests that, with ongoing opportunities to provide peer feedback and reflect on writing transfer from providing that feedback, learners became more inclined to draw far writing transfer insights from providing peer feedback.

While this movement toward far-transfer insights might afford writers greater writing growth, some research suggests that we should not be so quick to dismiss the value of low-road and near transfer. Donna Qualley, for instance, argues that low-road transfer can be quite valuable in certain contexts for writing growth, and emphasizes the slippage between low-road and high-road/near and far transfer.

Demonstrating the value of low-road transfer, two subsets of the near-transfer responses are worth highlighting. The first subset consists of 184 near-transfer responses that addressed a peer’s project topic or EC’s theme, “Achieving Expertise”:

I learned a little bit more about the country of Latvia;

I learn [sic] a brief history of Intel, how it succeed[ed] and lost the initial race in the mobile world. I find it is interesting.

I like that the author added one more element - passion - to the discussion of how to create expertise;

To be more practical and understand that there are several problems (economic, social, vision of the future) that can prevent people to acquire expertise.

While these near-transfer insights focus on content rather than writing, and could therefore be labeled transfer denial, they do have considerable value in the context of writing transfer from providing peer feedback. Since these transfer reflections occupied part of the peer-feedback/evaluation rubrics, and were therefore visible between peers, such near-transfer insights show learners engaging with peers as “authentic audiences” (Elon) who are reading, paying attention to, and learning from one another’s writing.

The second subset of near-transfer responses that highlights the value of near transfer within the context of providing peer feedback involves near-transfer insights connected with the final versions of projects. In these seventy-one near-transfer reflections, learners made direct reference to how providing peer feedback helped them think about what they “should have” or “could have” done differently in their final versions: I could have probably done a little extra research for my argument; I should have integrated a title in my text and I should have expressed more ideas of mine; I should have chosen a broader topic and used less jargon. While these near-transfer reflections may be focused solely on a particular project, they show how providing peer feedback and reflecting on writing transfer can help writers improve writing projects currently in development as well as build longer-term self-assessment skills and metacognitive awareness.

The ninety-three responses coded as transfer denial demonstrate resistance to articulating any transfer, such as Nothing specific; I don't know; No comments. Research suggests that with greater prompting to consider writing transfer, writers can move away from transfer denial (Jarratt; Wardle). However, transfer-denial responses emerged with significant distribution in this study, raising questions about this possibility. For example, these transfer-denial responses emerged from thirty-four different learners, such that 22.6% of learners in the study were inclined toward transfer denial at some point in the course. Twenty-four learners exhibited transfer denial only once. No learners demonstrated transfer denial in every response.

Transfer denial also occurred at varying times across the course, with both drafts (36) and revisions (57), and across all four projects: Project 1 (21); Project 2 (34); Project 3 (24); and Project 4 (14).{13} This somewhat wide distribution of this small set of transfer-denial responses serves, therefore, as a caution that transfer denial can persist even with sustained and explicit prompting, and points to the dynamic complexities of dispositions toward writing transfer.

3. Dispositions & Writing Transfer from Providing Peer Feedback

Perhaps the most complex element of writing transfer is disposition, which makes writers more or less inclined toward writing transfer in any given occasion, and is influenced by such matters as emotional affects, habits of mind, self-efficacy, motivation, values, attribution, and self-regulation (Driscoll, Connected; Klassen; Wentzel; Abdel Latif). The 3,404 responses suggest that inviting writers to reflect on writing transfer from providing peer feedback generates primarily positive dispositions toward writing transfer and provides opportunities for writing faculty to understand dispositions in more nuanced ways, offering insights into the intricate, dynamic complexities of dispositions.

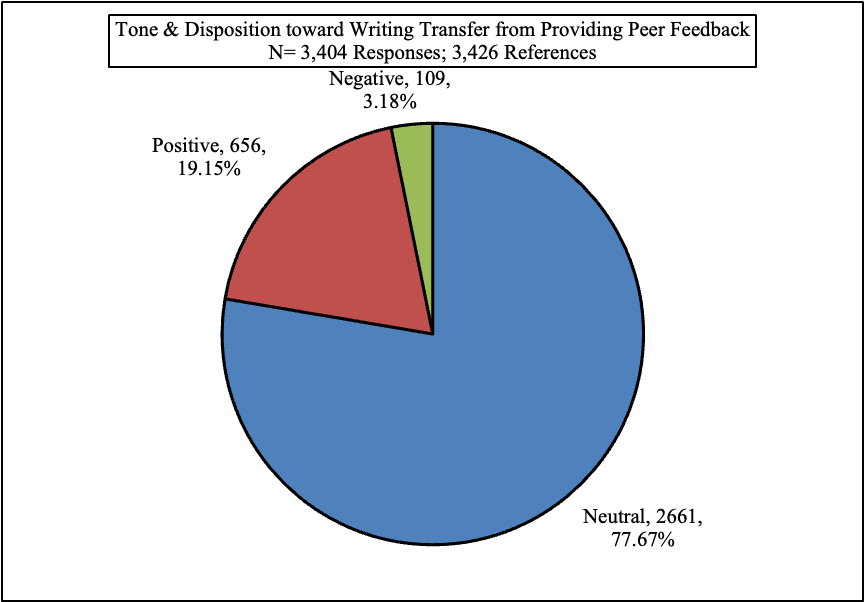

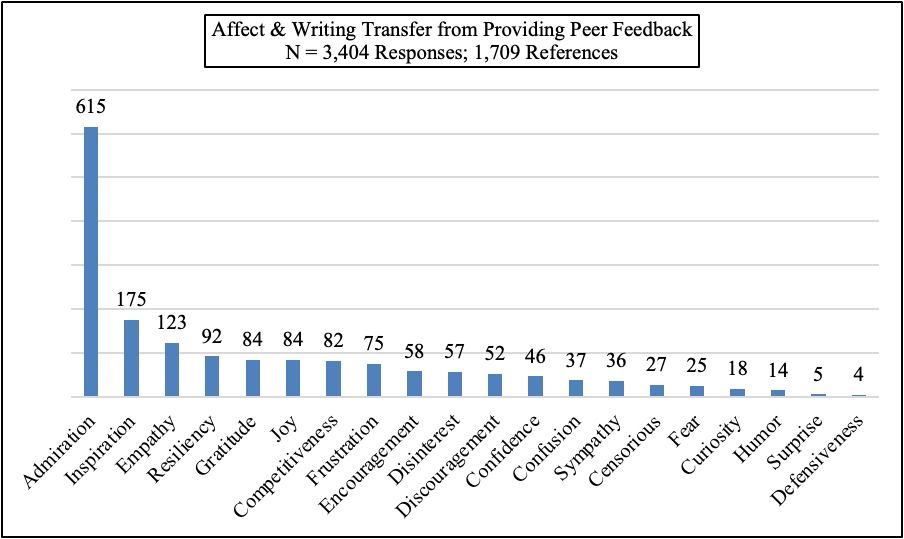

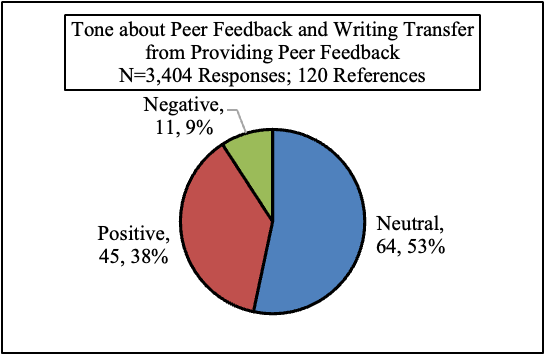

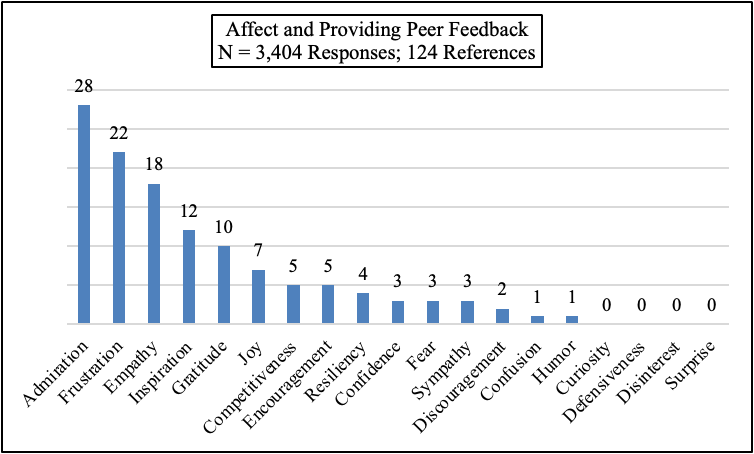

Figures 7 {14} and 8 {15} show, respectively, tone and emotional affect{16} across the responses. Of the responses, 96.22% exhibited either neutral or positive tone, and only 3.46% of responses exhibited negative tone. The six most frequently coded affects were all positive—admiration, inspiration, empathy, resiliency, gratitude, and joy—together comprising 68.64% of all references coded for affect. By contrast, affects such as disinterest and discouragement account together for only 3.18% of all affect references.

Figure 7. Tone.

Figure 8. Affect.

The 656 positive-tone responses primarily involved praise for peers and were usually correlated with the two most prevalent affects: 478 alongside admiration, e.g., I loved the way the author made use of vocabulary, and 111 alongside inspiration, e.g., I liked the writer's comparison of accountant to detective, and would like to use more original metaphors and comparisons in my own writing. Research focusing on the peer feedback writers receive often positions praise as less effective than criticism. Scholars have associated praise with lower-skilled reviewers, suggested that criticism comments are more likely to enact revision, and correlated the capacity to provide criticism with student performance (Cho and Cho; L. Li et al.; Lu and Zhang; Topping et al.; Nelson and Schunn).

However, in the context of reflecting on writing transfer from providing peer feedback, praise demonstrates learners identifying meaningful opportunities for writing transfer through praise. The following admiration example, for instance, shows an insight about conclusions: I was reminded that a powerful ending makes a big difference. Ending a race with a fast sprint to the finish line!! Your questions raised at the end kept me thinking after I had finished reading. And the following inspiration example reflects on the writer’s rhetorical relationship with writing subjects: My case study is also about a topic that is part of my experience/daily life but I haven't mentioned it in my paper as I didn't want to sound too personal/self-involved. [Peer’s Name,] you have shown me that it is possible to write about something that is part of your life and keep a "healthy" distance.

Negative-tone responses as shown in Table 5,{17} were distributed more widely across affects than positive-tone responses and emerged from forty-three different learners, or 29% of participants. These negative-tone responses demonstrate how the practice of integrating sustained reflections about writing transfer from providing peer feedback offers important pedagogical opportunities regarding learner dispositions and insights into the dynamic variability of dispositions toward writing transfer.

Table 5. Negative-Tone Responses.

| Affect | Negative Tone |

|---|---|

| Censoriousness | 27 |

| Frustration | 27 |

| Discouragement | 20 |

| Competitiveness | 17 |

| Admiration | 8 |

| Sympathy | 8 |

| Disinterest | 6 |

| Confusion | 5 |

| Empathy | 4 |

| Encouragement | 2 |

| Fear | 2 |

| Humor | 2 |

| Inspiration | 2 |

| Gratitude | 1 |

| Resiliency | 1 |

Twenty-seven (24.77%) of the 109 negative-tone responses exhibited censoriousness to peers’ writing. These twenty-seven responses ranged from somewhat mild, e.g., Not very impressive, to quite sharp: I was totally distracted while reading this article. It needs more concentration and more evidence. It is biest [sic] and too shallow. Given that the question about writing transfer from providing peer feedback appeared after nine open-ended questions on the formative peer-feedback rubric for drafts and after opportunities for evaluation and “overall comments” on the evaluative peer-feedback rubric for final versions (see Appendix A), such responses also exhibit transfer denial, whereby these learners chose to respond to the question about writing transfer by criticizing peers’ drafts instead of considering their own writing growth. Censorious responses emerged from fifteen learners, who together generated approximately 375 feedbacks across EC, suggesting that transfer resistance and censoriousness are not necessarily sustained aspects of learner dispositions but instead arise at a particular moment or in response to a particular peer’s draft.

The combined forty-seven negative-tone responses exhibiting frustration and/or discouragement, e.g., I wonder how other [sic] can write such beautiful description and I can't, offer similar insight into the dynamic variability of self-efficacy and attribution.{18} Twenty-three learners (15%) exhibited discouragement in one or more response, and forty-two learners (28%) exhibited frustration in one or more response, only nine of whom also expressed discouragement. Meanwhile, nineteen learners (13%), seven of whom never exhibited frustration or discouragement, expressed writing-related fear, e.g., I gave this author advice which I think I myself could use and that is to write and not to be afraid of it, or writing-related anxiety, e.g., It made me worry… my conclusion of my essay didn't actually answer the question I posed myself.… I worry I've tricked myself into accepting the appearance of a rational argument rather than an actual rational argument. Altogether, then, even though negative-tone responses were quite small (3.18%; see Figure 7), 42% of learners at some point expressed discouragement, frustration, or fear/anxiety. Such insights show how variable writing-transfer dispositions can be and how a sustained and iterative approach to inviting students to reflect on writing transfer from providing peer feedback can enable writing faculty to gain insights into and tailor pedagogy towards these shifting student dispositions.

Alongside self-efficacy and attribution, value towards writing writ large or a particular writing occasion also influences writing-transfer dispositions (Driscoll and Wells). Responses suggest that a focus on writing transfer from providing peer feedback yields positive valuing of writing and peer feedback. Positive reflections on why writing matters and on learners’ relationships with writing appeared in 537 references, e.g., I learned that it is so important to connect to what you are writing about, and how that connection brings intensity to the written word, and how that intensity then springs off the page directly into the reader's consciousness. Some referred to how writing can positively impact a reader: I learned that a good piece of writing can bring a smile to your face!; Awesome description … This changes my mood completely and I do hope, I would be able to do the same to others.

Writers’ perceived value of peer feedback has been the subject of much research in writing studies, with findings suggesting that many writers have negative attitudes toward peer feedback in comparison to instructor feedback, and often perceive peer feedback itself as a mixed enterprise (Liu and Carless; Kaufman and Schunn). However, Figure 9 shows that when learners directly referenced peer feedback, they were approximately four times more likely to exhibit a positive than negative tone.

Figure 9. Tone about Peer Feedback and Writing Transfer from Providing Peer Feedback.

The following examples demonstrate this valuing of peer feedback by focusing on writing transfer from providing peer feedback: I had the feeling that when responding to other classmates [sic] drafts I was re-writing (almost simultaneously) my own draft…; I learnt that I should formulate more powerful conclusions that makes reader [sic] think more about the subject. Thanks to this review I know it can be done by posing question [sic], for example. As Figure 10 shows, of the 124 references to peer feedback, 64.52% exhibited the positive affects of admiration, empathy, inspiration, gratitude, joy, and encouragement. By comparison, only twenty-two (17.7%) responses referencing peer feedback exhibited frustration, e.g., Having an experienced writer provide feedback is more effective than comments from a general audience of readers; Nothing and 7 different evals.

Figure 10. Affect and Providing Peer Feedback.

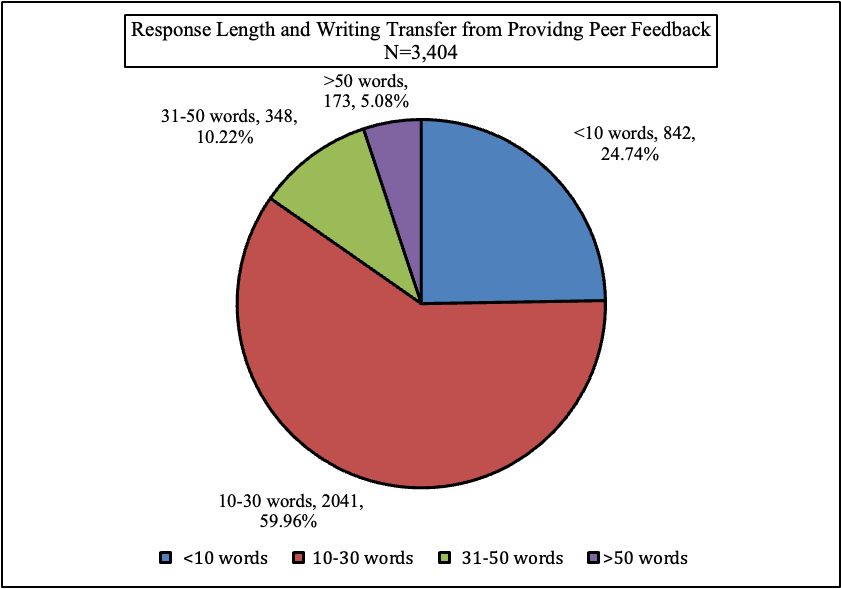

Another possible marker of value as it relates to dispositions involves response length. Figure 11 shows response length, and again confirms that dispositions can vary considerably even for one learner.

Figure 11. Length of Learner Response about Potential Writing/Learning Transfer.

The 24.74% <10-word responses emerged from 130 learners, such that 86.7% of learners wrote a <10-word response at some point during the course. While eighty-one of these responses exhibited transfer denial and/or disinterest, e.g., OK, Efforts, Nothing; Not much, the other 90.38% also exhibited near or far transfer, e.g., I should use more references, but still suggest in their brevity that the learner was choosing not to engage as deeply as they might otherwise with writing transfer. This distribution was similar with the 5.08% >50-word responses, which emerged from fifty-six learners, such that 37% of participants wrote a >50-word response at some point. Moreover, the fifty-seven responses exhibiting the affect of disinterest emerged from seventeen learners. Insofar as response length and/or disinterest is a possible indicator of value and disposition toward writing transfer, then, this distribution suggests that learners’ investment in writing varies across writing occasion and/or time.

A key mechanism for cultivating higher valuing of writing, particularly around writing transfer, involves forming what the Elon Statement on Writing Transfer describes as productive “communities of practice.” One hundred fifteen responses referenced community, wherein learners shared writing strategies, e.g., I can’t wait to back [sic] to it (my own draft) and apply the reverse outline myself. I strongly suggested the writer use the reverse outline knowing I was giving her my own self acknowledged best advice!, or used writing to forge peer connections: I had a chance to read a different way to say the same thing I tried to say in my work. I would be happy to exchange work again if you'd like. My email is…. Even when criticizing, many learners’ responses exhibited awareness of community, as in the following use of “friend”: This friend did not revise before submitted [sic] the homework… he had good ideas but because of the time or editing act, he did not realize about how to outile [sic] this text.

Reflecting on writing transfer from providing peer feedback created space for positive affect associated with writing, such as joy, e.g., I learned that a good piece of writing can lift your spirits!, and gratitude, e.g., Thank you for getting your reader to delve deeper into certain claims. I certainly appreciated that. If one of the aims of the course is to improve our writing through reading the writing of others, you definitely did that for me. References coded for empathy,{19} an important component of writing that surfaces connections across difference and contributes to literacy development (Blankenship; Lindquist; Junker and Jacquemin), also speak to this positive community of practice, e.g., I learned that I am not the only one who struggles with the idea of letting my own voice be heard in my writing.

This latter response also demonstrates what Beth Godbee terms “troubles talk,” where writers commiserate about writing challenges, e.g., I learned… that getting thoughts to flow more fluidly is a challenge I struggle with, frustrations, e.g., I found this assignment really difficult, and discouragements, e.g., Note to the writer of this piece—I expect a really low feedback score as well. Such responses show how reflecting on writing transfer from providing peer feedback can create important space for such troubles talk.

Identity shapes communities of practice and impacts dispositions toward writing and learning transfer (Hall, et al.). Phillip L. Hammack defines identity as intersecting cognitive, social, and cultural factors that form an “ideology cognized through the individual engagement with discourse, made manifest in a personal narrative constructed and reconstructed across the life course and scripted in and through social interaction and social practice” (223). While a fuller exploration of identity and writing transfer through providing peer feedback is beyond the scope of this article, two areas merit highlighting. Firstly, ten learners (6.67%) signaled at least once across their responses a cultural feature of their identities, either briefly, Regards from Romania, M—, or more extensively: I grew up in Philly and one of my favorite PBS shows is “Things That Aren't There Anymore.” It would have been great for me to write about. Secondly, twenty-nine learners (19.33%) across forty-one responses directly referenced English language learning, by referring to themselves, e.g., As English is not my native language, every essay gives me some new words and phrases that can be used in my next project, or by referring to their peers’ multilingualism, e.g., It’s really not necessary to have perfect English to convey ideas and messages effectively. As this latter comment suggests, none of these forty-one references exhibited negative tone, but instead emerged relatively evenly across neutral tone (23), and positive tone (18). Thirteen (31.7%) of these forty-one references also exhibited inspiration and encouragement, e.g., I am encouraged because like me there are many individuals around the world whose first language is not English doing a great effort to learn. I learned not be discouraged. Such responses, coupled with those directly referencing other aspects of cultural identity, show that reflecting on writing transfer from providing peer feedback can offer another positive space for communities of practice around identity and writing transfer.

Perhaps the most important marker of dispositions toward writing transfer, though, involves self-regulation, which “refers to self-initiated thoughts, feelings, and actions that writers use to attain various literary goals, including improving their writing skills as well as enhancing the quality of the text they create” (Zimmerman and Risemberg 76). This sort of meta-cognitive reflection is critical to writing transfer (N\9Fckles et al.). The practice of asking writers to reflect on writing transfer from providing peer feedback is itself meta-cognitive, creating sustained opportunities for writers to engage in meta-cognitive reflection, hone self-regulatory capacities, and share those habits of mind with peers to further reinforce these practices. Arguably, then, all the responses in this study other than the transfer-denial responses demonstrated self-regulation. But some did so in remarkable ways. The following learner, for example, reflects on “environmental and personal processes” (Zimmerman and Risemberg 76) shaping voice: I am scared to use a non-academic voice, since that is the voice that I honed in school and in my career. And, the following writer sets a specific goal while also demonstrating candid self-reflection: I'm not usually very daring in my writing. So I liked the personality of the piece, e.g. the use of 'dear reader'. That's something I would like to try with my writing. As a final example, the following learner shows self-regulation, along with attribution, by reflecting on how providing peer feedback can strengthen a self-identified area of improvement in writing: I struggle with paragraph unity and order as well as cohesion and this was a good example for me. The more I read compositions that I like and that I think flow smoothly I have a clearer idea of how to review my writing to ensure I do this better. Such metacognitive reflections show how creating ongoing space for writers to reflect on what they learned from providing peer feedback can contribute to the growth of self-regulation capacities and, in so doing, dispositions toward writing transfer.

Conclusions & Future Directions

Asking writers multiple times across a course to articulate what they gained from having provided peer feedback—and making these reflections visible among peers—yields important insights and points to areas for continued research. The results of this study suggest that providing peer feedback operates as a valuable threshold concept for writing studies, operating as a boundary concept, and inviting students to re-conceive providing peer feedback through the lens of writing transfer.

As they reflected on writing transfer from providing peer feedback, learners explored primarily HOC areas of writing knowledge across writing domains, demonstrated growth and inclination toward far, high-road transfer, and exhibited positive dispositions toward writing transfer and peer feedback. This study also shows that, in the context of reflecting on writing transfer from providing peer feedback, praise can be more beneficial than has been otherwise assumed, particularly when such reflections are visible among students. And, integrating meta-cognition around writing transfer from providing peer feedback enables faculty to understand in more nuanced ways individual learners’ shifting, complex dispositions toward writing transfer.

More research is needed to understand if metacognition around writing transfer from providing peer feedback yields improved quality of writing for those providing peer feedback, and how writers’ dispositions might be impacted to discover that their peers benefited as writers from having read their writing. While the heterogeneity of the MOOC learners suggests that reflecting on writing transfer from providing peer feedback has broad applicability, more research is needed to explore how this practice impacts the formation of writing communities of practice across different learning contexts and how such reflection intersects with identities and dispositions among various cohorts of learners.

To date, writing-transfer research has largely overlooked how providing peer feedback in the context of first-year writing offers a valuable threshold concept for writing transfer and a critical opportunity to teach or cue for transfer. Foregrounding this approach invites students to engage with the components of threshold concepts as defined by Wardle and Adler-Kassner: transformative, irreversible, integrative, and counterintuitive (2). These 3,404 responses demonstrate the immense potential of shifting the landscape for peer feedback to not only include—but to prioritize—writing transfer from providing peer feedback.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude goes to Ed White for consulting on EC assessment design; graduate-student researchers Layla Brown, Madeleine George, and Carla Hung, who conducted initial coding development and early coding; graduate-student research assistant Michael McGurk for reading and responding to drafts and editing; graduate-student research assistant Carolin Benack for proofreading the final version; Duke University Social Science Research Institute’s Nicole Wyman Roth for consulting on the methods section; and my colleague Eliana Schonberg for reading and responding to drafts. Preliminary results of this research were presented at the 2016 Conference on College Composition (Comer, Site) and the 2021 Writing Research across Borders Conference (Comer, Student). Funding for related previous research was provided by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Duke University Thompson Writing Program, Duke University Learning Innovation (then called the Center for Instructional Technology), and The MOOC Research Initiative, the latter with matching funds from the office of the Provost at Duke University. The MOOC Research Initiative is a project funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Appendices

Appendix A

EC Course Materials available at: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1hr5uBHrsg8WbBxqekmnj2zDjXVTtl-lv?usp=sharing

Appendix B

NVivo Codebook available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ayjKyaKn_URC0pFj_qWT-pwtACid8xCC/view?usp=sharing

Notes

{1} cf. Denise Comer and Ed White, Adventuring into MOOC Writing Assessment: Challenges, Results, and Possibilities.

{2} The following demographic data is from a pre-course survey (N=9,584); also see Comer and White, Adventuring into MOOC Writing Assessment: Gender: Female (49%), male (51%). Age: Under 18 (2.02%), 18–25 (27.15%), 26–34 (34.56%), 35–44 (18.75%), 45–54 (10.76%), 55–64 (5.21%), 65 or over (1.38%). Country of residence: Learners enrolled from 187 countries; the highest concentrations of residence were United States (20.43%), India (8.29%), Brazil (6.79%), Spain (5.54%), and China (2.96%). 77% of learners indicated English was not their first language, with self-identified written English proficiency of fluent (17.56%), proficient (40.61%), intermediate (37.07%), beginner (4.77%). Highest degree achieved: Less than high school (2.06%), secondary (8.89%), some college (14.67%), bachelor’s (36.95%), master’s (29.37%), and doctorate (4.06%). Employment: Precollege student (3.92%), undergraduate (15.09%), graduate student (17.17%), research scientist (6.24%), professional (26.19%), academic/professor (6.89%), teacher (10.29%), working full-time (37.31%), working part-time (13.34%), other (11.15%).

{3} In 1640 Ben Jonson identified reading “the best authors” as one of “three necessaries” for writing well (54). See also William Faulkner’s advice that writers read “everything—trash, classics, good and bad” (Rascoe 68) and Mike Bunn’s 2010 How to Read Like a Writer.

{4} As of 5 December 2022, EC has enrolled 681,044 learners, including 303,471 learners enrolled in its four session-based offerings (March 2013-August 2015) and 377,573 learners who have enrolled in its current on-demand format. For more on EC enrollment and completion rates, see Denise Comer and Ed White, Adventuring into MOOC Writing Assessment.

{5} Sample instructor feedback on anonymized submissions from learners who volunteered for feedback was posted to the EC course site; sample instructor feedback also emerged through synchronous writing workshops with members of the instructional team and selected learners, which were then recorded and made available on the course site to all EC learners.

{6} While peer feedback is ideally dialogic (Nicol), the MOOC necessitated anonymous, non-dialectic peer feedback through the Coursera platform. Peer feedback was central to EC from 2013-2020; EC shifted to an exclusive self-assessment model in February 2021 as part of a larger Coursera strategy.

{7} EC included four writing projects. When a learner submitted a draft, the EC platform distributed to that learner three peers’ drafts for peer feedback; when a learner submitted a final version, they received four peers’ final versions for peer evaluation (see also Table 1).

{8} Course completers were defined as learners who had submitted all four writing projects and earned an overall course grade of at least 70%.

{9} cf. Denise Comer, Charlotte Clark, and Dorian Canelas, Writing to Learn and Learning to Write.

{10} Of the 82,820 learners who enrolled across the first iteration of EC, 1,289 people earned a Statement of Accomplishment, defined as a grade of 70% or higher. cf. Denise Comer and Ed White, Adventuring into MOOC Writing Assessment: Challenges, Results, and Possibilities.

{11} While most responses evidenced either near or far transfer, 174 responses had equal focus on both; these were coded as both near and far transfer, resulting in 3,753 references.

{12} Figure 5 compares drafts and revisions for only Writing Projects 1-3 because Project 4 had no draft stage and would therefore skew results.

{13} Project 4 had only a final version, and as such only half as many opportunities for feedback as the other project cycles.

{14} Some responses demonstrated both positive and negative tone, yielding a total of 3,426 references.

{15} While all 3,404 responses were analyzed for affect, some responses did not convey any affect, and some conveyed multiple affects.

{16} Amy Williams defines affect as that which “concerns bodies and how they perceive, respond to, resonate with, interpret, and evaluate the forces and objects they encounter” (70).

{17} Some responses exhibited more than one affect, yielding 139 negative tone references across affects.

{18} Albert Bandura defines self-efficacy as “people’s beliefs in their abilities to produce given attainments” (307). Irene Hanon Frieze and Bernard Weiner define dispositional attribution as how “observers… attribute… success or failure of an actor to… causal factors such as ability, effort, task difficulty, and luck” (Reeder and Brewer 61). Writers’ beliefs about the degree to which their abilities, efforts, and luck will enable them to succeed or fail at a given writing task impact writing transfer, growth, and performance (McCarthy et al.; Driscoll and Wells).

{19} Nathan Spreng et al. define empathy as “social cognition that contributes to one’s ability to understand and respond adaptively to others’ emotions, succeed in emotional communication, and promotes prosocial behavior” (62). Jess Kerr-Gaffney et al. distinguish between cognitive empathy, “the ability to recognize and understand another’s mental state,” and affective empathy, “the ability to share the feelings of others” (2).

Works Cited

Abdel Latif, Muhammad M. M. Unresolved Issues in Defining and Assessing Writing Motivational Constructs: A Review of Conceptualization and Measurement Perspectives. Special Issue: Framing the Future of Writing Assessment, vol. 42, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2019.100417.

Adler-Kassner, Linda, et al. The Value of Troublesome Knowledge: Transfer and Threshold Concepts in Writing and History. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, https://www.compositionforum.com/issue/26/troublesome-knowledge-threshold.php

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth A. Wardle, editors. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. Utah State University Press, 2015.

Aitchison, Claire. Writing Groups for Doctoral Education. Studies in Higher Education, vol. 34, no. 8, 2009, pp. 905–16. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070902785580.

Auerbach, Carl F., and Louise B. Silverstein. Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis. New York University Press, 2003.

Bandura, Albert. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review, vol. 84, no. 2, 1977, pp. 191–215. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State University Press, 2007.

---. Writing in the Real World: Making the Transition from School to Work. Teachers College Press, 1999.

Bitzer, Lloyd F. The Rhetorical Situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric, vol. 1, no. 1, 1968, pp. 1–14, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40236733.

Blankenship, Lisa. Changing the Subject: A Theory of Rhetorical Empathy. Utah State University Press, 2019.

Boud, David, and Elizabeth Molloy. Rethinking Models of Feedback for Learning: The Challenge of Design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 38, no. 6, 2013, pp. 698–712. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2012.691462.

Brown, Gavin T. L., et al. Teacher Beliefs About Feedback Within an Assessment for Learning Environment: Endorsement of Improved Learning Over Student Well-Being. Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 28, no. 7, 2012, pp. 968–78. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.05.003.

Bruffee, Kenneth A. Collaborative Learning: Some Practical Models. College English, vol. 34, no. 5, 1973, pp. 634–43. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.2307/375331.

---. The Brooklyn Plan: Attaining Intellectual Growth through Peer-Group Tutoring. Liberal Education, vol. 64, no. 4, 1978, pp. 447–68.

---. What Being A Writing Peer Tutor Can Do for You. Writing Center Journal, vol. 28, no. 2, 2008, pp. 5–10. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.7771/2832-9414.1700.

Bunn, Mike. How to Read Like a Writer. Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, edited by Charles Lowe et al., vol. 2, Parlor Press, 2010, pp. 71–86.

Carless, David, et al. Developing Sustainable Feedback Practices. Studies in Higher Education, vol. 36, no. 4, 2011, pp. 395–407. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/03075071003642449.

Chaktsiris, Mary G., and James Southworth. Thinking Beyond Writing Development in Peer Review. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2019.1.8005.

Cho, Kwangsu, Christian D. Schunn, et al. Learning Writing by Reviewing in Science. 2007.

Cho, Kwangsu, Moon-Heum Cho, et al. Self-Monitoring Support for Learning to Write. Interactive Learning Environments, vol. 18, no. 2, 2010, pp. 101–13. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820802292386.

Cho, Kwangsu, and Charles MacArthur. Learning by Reviewing. Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 103, no. 1, 2011, pp. 73–84. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021950.

---. Student Revision with Peer and Expert Reviewing. Learning and Instruction, vol. 20, no. 4, 2010, pp. 328–38. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.08.006.

Cho, Young Hoan, and Kwangsu Cho. Peer Reviewers Learn from Giving Comments. Instructional Science, vol. 39, no. 5, 2011, pp. 629–43. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23882823.

Comer, Denise K. English Composition 1. Coursera, 18 Mar. 2013, https://www.coursera.org/learn/english-composition.

---. Providing Peer Feedback as a Site of Writing Transfer. 2016.

---. Providing Peer Feedback: Student Learning Gains in Writing and Learning. 2021.

---. Writing in Transit with Readings. Fountainhead Press, 2017.

Comer, Denise K., et al. Writing to Learn and Learning to Write across the Disciplines: Peer-to-Peer Writing in Introductory-Level MOOCs. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, vol. 15, no. 5, 2014, pp. 26–82.

Comer, Denise K., and Edward M. White. Adventuring into MOOC Writing Assessment: Challenges, Results, and Possibilities. College Composition and Communication, vol. 67, no. 3, 2016, pp. 318–59.

Coyle, Daniel. The Sweet Spot. The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How, Bantam Books, 2009, pp. 11–29.

Cross, Susan, and Libby Catchings. Consultation Length and Higher Order Concerns: A RAD Study (1). WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, vol. 43, no. 3–4, 2018, pp. 18–25. Gale Academic OneFile.

De Guerrero, Maria C. M., and Olga S. Villamil. Activating the ZPD: Mutual Scaffolding in L2 Peer Revision. The Modern Language Journal, vol. 84, no. 1, 2000, pp. 51–68. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00052.

DeFeo, Dayna Jean, and Fawn Caparas. Tutoring as Transformative Work: A Phenomenological Case Study of Tutors’ Experiences. Journal of College Reading and Learning, vol. 44, no. 2, 2014, pp. 141–63. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2014.906272.

Devitt, Amy J. Writing Genres. Southern Illinois University Press, 2010.

Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisioning ‘First-Year Composition’ as ‘Introduction to Writing Studies.’ College Composition and Communication, vol. 58, no. 4, 2007, pp. 552–84.

---. Connected, Disconnected, or Uncertain: Student Attitudes about Future Writing Contexts and Perceptions of Transfer from First Year Writing to Te Disciplines. Across the Disciplines, vol. 8, no. 2, 2011, pp. 1–29. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.37514/ATD-J.2011.8.2.07.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Bonnie Devet. Transfer of Learning in the Writing Center. 2020.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, et al. Genre Knowledge and Writing Development: Results From the Writing Transfer Project. Written Communication, vol. 37, no. 1, 2020, pp. 69–103. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088319882313.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Jennifer Wells. Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012.

Elon Statement on Writing Transfer. https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/elon-statement-on-writing-transfer. Accessed 15 Feb. 2022.

Falchikov, Nancy, and Judy Goldfinch. Student Peer Assessment in Higher Education: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Peer and Teacher Marks. Review of Educational Research, vol. 70, no. 3, 2000, pp. 287–322. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543070003287.

Ferris, Dana R. The Influence of Teacher Commentary on Student Revision. TESOL Quarterly, vol. 31, no. 2, 1997, pp. 315–39. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.2307/3588049.

Frieze, Irene, and Bernard Weiner. Cue Utilization and Attributional Judgments for Success and Failure. Journal of Personality, vol. 39, no. 4, 1971, pp. 591–605. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1971.tb00065.x.

Gielen, Mario, and Bram De Wever. Structuring Peer Assessment: Comparing the Impact of the Degree of Structure on Peer Feedback Content. Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 52, 2015, pp. 315–25. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.019.

Godbee, Beth. Toward Explaining the Transformative Power of Talk about, around, and for Writing. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 47, no. 2, 2012, pp. 171–97. JSTOR.