Composition Forum 51, Spring 2023

http://compositionforum.com/issue/51/

Composition Studies and Transdisciplinary Collaboration: An Overview, Analysis, and Framework for University Writing Programs

Abstract: Universities across the globe have begun to invest in transdisciplinary research: a complex form of collaboration that places divergent disciplinary specialists and community members in participatory research aimed at addressing an applied research question. For a collaboration to succeed in this knowledge work, participants must engage in radical boundary crossing among disciplinary and community knowledge cultures wherein language is the substance of these boundaries and crossings. Effective collaboration, communication, and writing are essential to the success of transdisciplinary research, but composition research on collaborative writing has yet to address what collaboration looks like in transdisciplinary settings. This article offers a theoretical synthesis that brings transdisciplinary research theory into conversation with composition theory and pedagogy by providing an overview of the core principles of transdisciplinary research, offering an activity systems interpretation of transdisciplinary research, and outlining a framework for incorporating transdisciplinary collaboration into university composition programs.

What approach to policing will eliminate the killing of unarmed citizens?

Which economic policies alleviate human poverty?

How do we assure that people experience total social and economic equality regardless of race or ethnicity?

How should humans respond to climate change?

How can we develop a sustainable energy infrastructure?

Questions like these, and thousands of related questions, are among the most challenging research problems faced by humanity in our time. These are problems of premiere importance to citizens, communities, governments, organizations, academic disciplines, and universities alike—problems with which students and universities are and ought to be eagerly and urgently engaged. Sometimes referred to as “wicked” because of their prevalence and complexity, these problems and their ensuing questions resist simple explanation and the comforts of controlled disciplinary inquiry. Instead, wicked problems like climate change, poverty, systemic racism, and economic inequality require equally complex modes of inquiry because these issues don’t fit neatly within the purview of a single discipline like criminal justice, economics, law, or even an interdisciplinary discipline like environmental science. Today’s university students are on the frontline of these problems and are grappling with these issues and their complexities, which begs some questions.

How is writing studies positioned and implicated in all of this? What can composition programs do to rise to this challenge and help students navigate these issues and their complexities? Is the disciplinary and departmentalized design of higher education sufficient for meeting these challenges? I have doubts.

The problems of climate change, poverty, systemic racism, and economic inequality require collaboration among disciplinary specialists, yes, but also require collaboration among organizations, professional associations, and ordinary citizens. Thus, wicked problems are challenges that must be addressed collaboratively across disciplines, organizations, and alongside communities and ordinary citizens. The writing studies curriculum in many universities is often the space where this thinking about disciplinarity, academic discourse, audience, community engagement, and collaboration takes place, but if we are to prepare students to think about these contemporary problems we may need to reconsider how we approach these conversations. The domain of academic inquiry for wicked problems is often referred to as Transdisciplinary Research.

Transdisciplinary Research is a collaborative approach that integrates knowledge cultures as early as possible in the inquiry process—in the conceptualization of problems and the formation of research questions. Knowledge cultures, a term adopted in Valerie Brown et al.’s extensive cataloging of transdisciplinary research methods, includes groups such as academic disciplines and specialists, community representatives, individuals, organizations, and holistic thinkers (i.e. artists). The collaborative integration of these bodies of knowledge early in the process of inquiry diverges drastically from traditional disciplinary and multi-disciplinary approaches to inquiry in our universities that:

don’t often integrate knowledge groups outside of academic disciplines (beyond the proverbial “ivory tower” where knowledge is made outside the gaze and influence of non-specialists); and

where integration among disciplines typically occurs late in the inquiry process—once the problem has already been conceptualized, research questions posed, methodologies developed, and conclusions reached by respective knowledge cultures (multi-disciplinarity).

Transdisciplinary research comes down to who is at the table and when they get invited: both the placement of collaboration at the outset of an inquiry process (in the very forming of research questions) and collaboration with diverse knowledge cultures—not just academic disciplines—that differentiates transdisciplinary research from other modes of inquiry like multi-disciplinarity or community-based participatory research.

Transdisciplinary research is at the very center of twenty-first century knowledge making, and yet it is a domain that writing studies and composition research has hardly begun to consider. This article tries to take on some of this work by offering a theoretical synthesis between two complex bodies of literature (transdisciplinary collaboration and its connective tissue to composition studies) with the aim of constructing a framework for composition programs to incorporate transdisciplinary preparation into university writing programs, including first-year writing and Writing Across the Curriculum/Writing in the Disciplines (WAC/WID) curricula. The complexity of this emerging approach to knowledge work and inquiry is an important site of scrutiny for composition studies research, especially for communication, first-year writing, technical and professional writing, and WAC programs. If we accept the premise that our universities are charged with helping students approach the prevailing research questions of our time through dialogic inquiry—a role for which composition and communication programs are historically positioned—than we ought to take a critical look at this emerging trend of transdisciplinary research and carefully consider how college composition and communication programs can contribute to student success in these collaborations. Programmatic planning aside, it may also be the case that the solutions we need to address some of our most pressing societal problems like economic inequality, criminal justice reform, and climate change will hinge upon our students’ future success in transdisciplinary research collaborations. In this way, successful collaboration across disciplines and knowledge cultures is a pedagogical concern as well as professional, cultural, and civic concern.

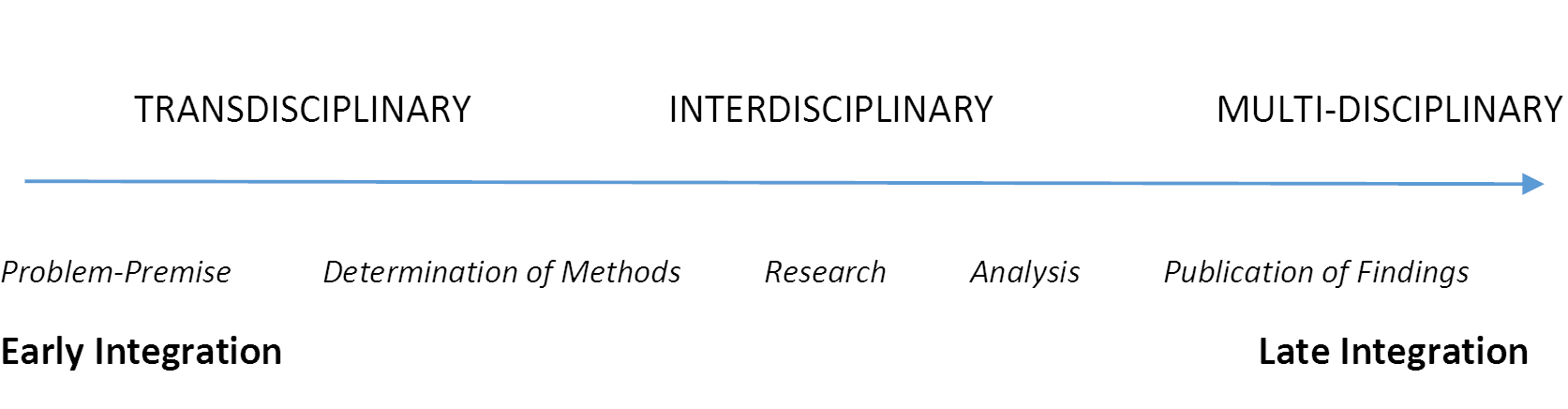

To consider transdisciplinary research’s potential value to composition theory, we might start by considering where discourse about transdisciplinary research and collaboration is already present in our mosaic of subfields. For composition studies, transdisciplinary research can be understood as requiring the synthesis of several substantial domains of existing scholarship: civic-engagement theory and community based participatory research (CBPR), WAC/WID pedagogy, collaborative writing theory, and composition pedagogy to name just a few. Within each of these scholarly domains we see growing explorations of transdisciplinarity, and more often: inter- and multi-disciplinarity (delineated in Figure 1). Using activity theory, this article offers a synthesis of some of the core principles and themes in transdisciplinary collaboration with attention to how transdisciplinarity may trouble some of the core tenets of composition theory and the departmentalized approach to university curricula. This article will also discuss some opportunities and limitations for composition programs looking to prepare students for transdisciplinary collaboration and outline a framework for composition programs looking to prepare students for transdisciplinary work.

A Note on Method

An application of activity systems theory to transdisciplinary literature is useful in this case because activity theory helps capture the work of language as it moves through complex discursive environments. David Russell’s 1997 Rethinking Genre in School and Society helped connect activity systems theory to rhetorical genre studies, writing in the disciplines theory, and composition studies writ large. Russell’s aim was to determine how academic genres translate into social practices and he subsequently developed a genre view of activity systems that would come to be preferred over the more slippery uses of “discourse communities” (Swales) or “communities of practice” (Lave and Wenger) that sought to label discursive environments in which disciplinary knowledge production occurred. Activity systems theory understands genre as a “basic unit of analysis of behavior, individual and collective” and Russell defines activity systems as “any ongoing, object-directed, historically conditioned, dialectically structured, tool-mediated human interaction” (510). The composition studies researcher that has most significantly advanced David Russell’s 1997 uptake of activity theory into a unit of analysis is Clay Spinuzzi. Spinuzzi’s 2011 work Losing by Expanding: Corralling the Runaway Object successfully articulates the challenges writing studies researchers face in applying traditional activity theory (labeled as Third Generation Activity Theory or 3GAT) to the expansiveness of contemporary objects and problems. Spinuzzi critiques seven case studies in professional communication that utilize 3GAT and argues that objects are treated inconsistently in the works analyzed. Spinuzzi argues that objects must be the “linchpin” that bound an activity system for the analysis to be sound. While other composition researchers have utilized institutional ethnography as an analytical tool for disciplinary systems (see LaFrance and Nicolas), the theoretical principles of citizen-engagement and public participation in transdisciplinary research means that an analysis must extend beyond our institutions’ ruling relations and consider transdisciplinary research in the wider context of an activity system.

Making Sense of Transdisciplinary Research for Composition: An Overview and Activity Systems Review

Transdisciplinary theory is a robust topic of study that has been characterized across volumes of academic literature in domains that include health sciences (Creswell), humanities (Klein), political science (Shapiro), rhetoric and composition (Kells; Rodriguez and Helena; Rademaekers; Mays and McBride), social sciences (Leavy), sustainability studies (Brown et al.), and writing program administration (Serviss and Voss). While the levels of detail range widely in these works that characterize transdisciplinary research methodologies, some common principles persist for transdisciplinary research method regardless of disciplinary domain. Here is a very brief review of three widely agreed upon principles of transdisciplinary research from which we might begin to consider a composition theory framework for facilitating such collaborations:

Principle 1: In transdisciplinary research, participants are conceptualized more broadly as representatives of “knowledge cultures”

Principle 2: Research questions addressed in the collaboration are applied, conceptualization-centered, and problem-centered in nature

Principle 3: In transdisciplinary research, collaborating knowledge cultures integrate at the earliest stages of inquiry—in the very conceptualization of the problem and invention of research questions

Principle 1: collaborating participants are conceptualized more broadly as representatives of “knowledge cultures”

Patricia Leavy’s 2011 contribution to transdisciplinary theory—Essentials of Transdisciplinary Research—argues from a social science perspective that collaboration is vital to transdisciplinary method. Leavy summarizes a transdisciplinary project known as the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network, or TBCCN. Researchers interested in health disparities across demographic groups focused on colorectal cancer treatment disparities within the African American community in Tampa Bay, Florida. Leavy explains “this is a transdisciplinary topic by nature. In order to get at the relevant issues, research needs to connect different bodies of knowledge from the natural sciences, environmental sciences, and social sciences” (85). The initial phase of research for the TBCCN focused on academic research of colorectal cancer across “three ethnic subgroups of US Blacks” but quickly “[t]he research team recognized that in order to garner support and participation from the community of interest it was vital to employ the principles of community-based participatory research” (86). New collaborations soon developed among cancer researchers, geographic information systems (GIS) experts, and members of a cultural advisory group created for the purpose of participatory research. It was through this engagement with the cultural advisory group that issues tangential to cancer screenings in the community became integrated into the research. Leavy explains “clearly, in order to effectively address this topic...bodies of literature that deal with racism, gender, race and healthcare, and the public’s perception of cancer, all needed to be a part of any comprehensive approach to this problem” (86-7). As Leavy’s case of the TBCCN details, transdisciplinary research doesn’t lend itself to neat disciplinary silos of research; instead, transdisciplinarity requires collaboration not just among diverse academic disciplines like cancer researchers and social scientists studying race and healthcare—but also requires collaboration among these disciplines and the community.

So, who collaborates in transdisciplinary research writing? The classification of individual and group collaborators into sets of “knowledge cultures” in transdisciplinary research was popularized by Brown et al. in their introductory chapter “Towards a Just and Sustainable Future” in the oft cited 2010 collection Tackling Wicked Problems through the Transdisciplinary Imagination. The authors articulate five recurring knowledge culture groups in transdisciplinary research:

individuals involved

the local community

relevant specializations

influential organizations

holistic thinkers

“Each of these [knowledge cultures] proved to have theirir own form of inquiry, sources of evidence, timescale for action and even their own language” (11). Is this much different from our own classrooms?

From a writing studies perspective, we can see spaces where our scholarship has already begun to prepare us to address such collaborations. Work in the rhetoric of science and WAC/WID have contributed extensively to understanding the differences among academic disciplines, the distinct knowledge cultures that emerge from disciplinary epistemologies, and the challenges of interdisciplinarity (Samraj and Swales; Zawacki and Williams; Harris; Nowacek; Schaefer). Work in cultural studies and cultural rhetorics have detailed the ways that cultures, subcultures, and counter-cultures uptake diverse knowledge culture practices (Cintron; Bacon; Powell). Further, work in civic engagement, service learning, and community writing have explored the ways that university representatives—and writing programs—can ethically and equitably engage in community-based knowledge work (Parks and Goldblatt; Coogan). These all represent distinct areas of inquiry that our field has already undertaken and that a framework for writing program engagement with transdisciplinary research collaboration must synthesize.

Principle 2: Research questions addressed in the collaboration are applied, conceptualization-centered, and problem-centered in nature

Transdisciplinary research collaborations must pursue particular kinds of research questions as divergent knowledge cultures work to collaborate in the process of inquiry. Collaborators must work in the early stages of integration (see principle three below) to conceptualize problems that are a matter of applied research. This is the case because transdisciplinary research doesn’t lend itself to an address of disciplinary questions which are commonly distinguished as “pure research” or “normal science...characterized by continual competition between a number of distinct views of nature” (Kuhn, 5). The vast majority of work in normal science, according to Thomas Kuhn, is not focused on solving applied problems, but supporting the development of a paradigm and its prevailing questions. This is largely the work of academic disciplines to which community stakeholders aren’t often engaged or invited to engage. Normal science seeks methodological precision and elimination of ambiguities. In pure research today, normal science asks questions like: How does chemical X behave in the human body? Or, Does the Higgs-Boson particle exist? Before asking: How do we decrease cancer mortality in Tampa Bay? Or: How can we have a sustainable and efficient energy infrastructure? These latter questions: about reducing mortality or having sustainable energy resources happen in the domain of applied research and this applied research is the object of transdisciplinary research collaboration. Unlike normal science, transdisciplinary research is not focused on advancement of a disciplinary paradigm, per se, but resolution of an applied question or developing a collaborative conceptualization of a problem.

As a result of this focus, the problem determines the tools, methods, and subjects rather than an academic discipline or historical paradigm. To ask How can we have a sustainable and efficient energy infrastructure? A research collaboration needs input from academic disciplines like physics, electrical engineering, political science, economics, urban studies, the humanities, among others; but it also requires engagement with community: individuals, groups, and organizations. In the early integration of divergent knowledge cultures including knowledge cultures outside of the university we see the deep complexity and promising power of these transdisciplinary research collaborations. We might also see how our own composition classrooms are poised for such engagement.

Principle 3: Collaborating knowledge cultures integrate at the earliest stages of inquiry—in the conceptualization of a problem and development of research questions

Research inquiries can be depicted along a continuum that often begins with conceptualization of the problem and formation of questions and ends in a publication or communication of findings. In this continuum, the development of methods, the research itself, and the analysis of results take place in between problem conceptualizations and communication of findings. Yet oftentimes collaborators enter a collaboration at various stages in the continuum, and many collaborators begin collaborating after the problem has been conceptualized and questions have been developed. In such occasions, collaborators commonly take on an a priori problem-premise or conceptualization for the research and join to develop methods, enact research, analyze data, or share data with a mind toward publication. In transdisciplinary research, collaborators engage as early in the stages of inquiry as possible. What differentiates transdisciplinary research collaborations from other modes of collaboration is that the collaborating starts earlier in the process of inquiry than other modes of collaboration like interdisciplinary collaboration and multi-disciplinary collaboration (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Collaboration Levels Based on Stage of Knowledge Culture Integration in Research Inquiry

Leavy explains that multidisciplinary collaborations involve multiple disciplines, but that in this mode of collaboration “each discipline maintains its own assumptions, values, and methods” and “autonomy during the collaboration” (18). For example, a writing studies researcher might collaborate with an organization management researcher to determine how workplace writing tasks facilitate or inhibit incremental improvement of workplace processes, but the writing studies researcher needn’t adopt an ideographic action research methodology from the discipline of management, nor would the management research need to adopt observational methods from the rhetoric and composition discipline. In this hypothetical scenario, each research pursues their inquiry in their own way and integration becomes more likely late in the process, such as sharing findings and data to reach collaborative conclusions.

In interdisciplinary collaborations, Leavy explains, “there is a greater level of interaction between the disciplines” (20) wherein methodologies may be “combined” but “their guiding approaches are left intact” (21). Leavy and many others acknowledge that interdisciplinarity is the collaborative mode with the widest range, often to describe the terrain between transdisciplinarity and multidisciplinarity. For example, in an interdisciplinary collaboration among writing studies researchers and organizational management researchers we might expect the researchers to work side by side in conducting focus groups and recording observations. This would represent integration in the research itself and some mild dissolution of boundaries to combine research efforts, but not radically so.

The integration of divergent knowledge cultures (including academic disciplines and community members and groups) at the problem-premise and research question stages of inquiry is important in transdisciplinary research collaboration because it’s often in the conceptualization of the problem that collaboration among divergent knowledge cultures is most powerful. It is with these three principles in mind we can begin to consider a composition theory framework for writing programs interested in transdisciplinary research collaboration.

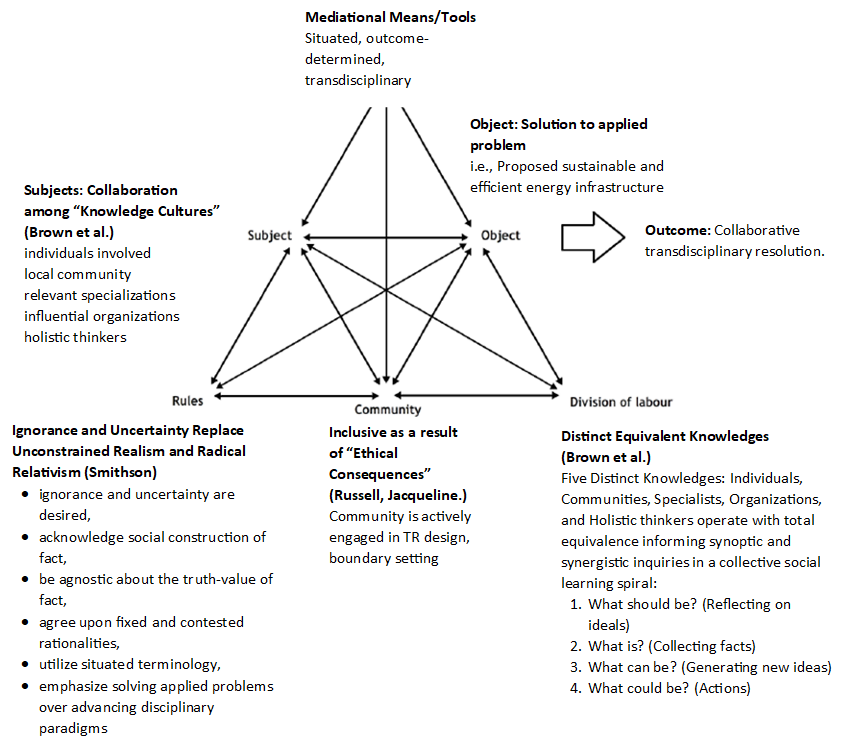

The activity systems analysis that follows will focus on transdisciplinary research collaboration as described in a case text that thoroughly outlines transdisciplinary research inquiry, Brown et al.’s Tackling Wicked Problems, and the analysis is later synthesized in an activity systems diagram presented in Figure 2.

Activity systems in the 3GAT methodology are organized around subjects’ use of rules, mediational means, divisions of labor, and function as a community in order to achieve an object-oriented objective. But these elements become quite nuanced and complicated in an activity systems model for transdisciplinary research collaboration. What follows is an elaboration of subjects, objects, and objectives in Brown et al.’s model for transdisciplinary research collaboration as well as an articulation of the rules, mediational means, divisions of labor, and operations as a community through which this framework has been theorized. This activity systems application to transdisciplinary theory can help codify transdisciplinarity for composition theory.

Subjects of Transdisciplinary Research Activity Systems

Brown et al. (2010) thinks about the diverse subjects of transdisciplinary research activity systems in terms of five “knowledge cultures” (11) repeated here for reference:

individuals involved

local community

relevant specializations

influential organizations

holistic thinkers

Each of these knowledge cultures inform the problem-centered outcome of transdisciplinary research in key ways. The role of academic disciplines in transdisciplinary research is largely encapsulated in the knowledge cultures of “relevant specializations” and “influential organizations” while students may be encapsulated as specialists or individuals, and the community is encapsulated by individuals, the local community, influential organizations, and holistic thinkers.

Objects and Outcomes in Transdisciplinary Research Activity Systems

In an ideal scenario, transdisciplinary research collaborations focus on the production of objects (like texts, legislation, agreements, proposals) to reach solutions that serve as outcomes. In the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network (TBCCN) described earlier, for example, we see that divergent disciplines and community members successfully collaborated around objects like community cancer resources and access to cancer screenings as they worked to achieve an outcome of reduced cancer mortality in the community. Yet many transdisciplinary research collaboration attempts fail to materialize into outcomes (as detailed in Rademaekers). In many cases the boundaries are too obstructive for objects to be shared (i.e. how can a community member, humanities researcher, and physicist co-author an article?) and the objectives are of too large a scale to be realized (i.e. how could we implement a global sustainability solution if proposed in a transdisciplinary research collaboration?). Thinking beyond direct implementation of solutions we see that empowerment and transformation may also become objects and objectives of a transdisciplinary collaboration. That is, if specialists, individuals, community members, organizations, and holist knowledge cultures reach a new conceptualization of a problem, or have their personal views of a problem transformed as a result of the collaboration, then this too becomes an outcome of the work.

Rules in Transdisciplinary Research Activity Systems

Because transdisciplinary research activity systems consist of a diverse group of subjects, including relevant specializations, the public, influential organizations, and individuals from diverse disciplinary frameworks, the methods, tools, and mediational means of their activities change accordingly. Some rules are needed to help achieve an egalitarian process for providing input as a member of the collaboration, but others have to do with ensuring a space where assumptions and values can be adequately debated in those early moments of integration. Transdisciplinary research collaborations can only succeed in developing problem-centered methodologies if they embrace two concepts, or rules, that seem antithetical to traditional inquiry: ignorance and uncertainty (Smithson, in Brown et al., 87). To acknowledge that we do not have answers to problems and that we are uncertain of our hypothesis is difficult for an information-based society. We need look no further than the health communication around a wicked problem like the recent COVID-19 pandemic to see just how uncomfortable these concepts are to infectious disease specialists, politicians, and citizens alike. To accept ignorance and uncertainty, for Smithson, is to acknowledge that terminology, methodology, and epistemology among divergent disciplines and community knowledge cultures may never be commensurable. Instead, transdisciplinary research collaborators must operate in the middle ground between two extremes: unconstrained realism and radical relativism.

Mediational Means/Tools

An activity systems approach understands written genres, in part, as mediational means/tools for action within the system and suggests careful consideration of genres which inevitably “operationalize” and reproduce the “ideological and material conditions that make up the activity system” (Bawarshi, 210). Transdisciplinary research collaborators must rely on genres that reproduce openness, situated knowledge making, and egalitarian relations among knowledge cultures. Recent research has proposed the “Wiki” genre as one such choice (Kasemvilas and Olfman), and other mediational genres for facilitating collaboration may include visual mapping and public-focused deliverables such as creating web-resources, grant proposals, and recommendation reports. These genres may be in stark contrast to genres that reproduce hierarchical relationships and emphasize historically European views of authorship, like academic journal articles or policy papers. Writing programs have long been invested in assignments that look beyond the gaze of university writing and try to model authentic genre engagement, and a composition theory for transdisciplinary research collaborations could further explorer the kinds of genres that facilitate openness, situated knowledge making, and equality among knowledge cultures in a collaborative transdisciplinary research course or assignment.

Community

In terms of activity systems, we see in transdisciplinary research that community takes an active role in informing subjects, their mediational means, and the object being pursued, which is different than the less direct role of community described in activity systems of Kuhn’s “normal science.” For Russell, what this systemic intervention approach to transdisciplinary research creates is “ontological, epistemological, and ethical commitments” which are “open” and consequently replace the “closed systems view” (53-57). An open ontology or open epistemology includes as “real” the “objective physical world, the inner subjective world of the individual, and the cultural sphere of the normative social world” which for Russell is the only way to ensure transdisciplinary research has legitimacy inquiring about “relationships between humans and their environments” (52).

If transdisciplinary research is situated, creates flexible boundaries, and is ethically extended to those affected by the research and the broader community then transdisciplinary research must also permit situated ontologies and situated epistemologies to remain open—to be critically deliberated regarding both facts and values. Perhaps with discomfort, this is to suggest that oil industry workers, and Arctic indigenous communities, and climatologists should all have a voice in a transdisciplinary research collaboration addressing an efficient and sustainable energy infrastructure.

The composition classroom is no stranger to synthesizing the divergent views of communities on issues like climate change, but the confines of classroom learning easily deduce these syntheses to consultation (by source material or interview) rather than collaboration (by engaging these representative communities equally in the collaborative project). Transdisciplinary research begs composition theory to ask what it would look like for students to write with communities not about them.

Division of Labor

Another characteristic of transdisciplinary research activity systems which extends from this notion of situated knowledge, is that information from multiple sources, not just multiple disciplines, informs transdisciplinary research collaboration. Here we see science extending beyond public engagement to public participation. Among participating knowledge cultures (individual, community, specialist, organization, and holistic), each exhibits distinct characteristics related to knowledge content, methods of inquiry, the types of questions being asked, the types of evidence valued, and the exemplars of each respective knowledge culture. Brown argues that authentic transdisciplinary research does not privilege the academic specialist, but “in accepting the equivalence of the knowledges from all the contributing parties, an open transdisciplinary inquiry recognizes the validity of each construction of knowledge and their particular tests for truth” (66-67).

While a lofty ideal, the total equivalence of these knowledge cultures has implications for the division of labor in transdisciplinary research activity systems. All the traditional divisions of labor in traditional inquiry remain in transdisciplinary research collaboration: specialists, funders, affiliate organizations. However, in transdisciplinary research the inclusion of the five distinct knowledge cultures further complicates the labor roles as well as the expectation of total equivalence among these labor roles.

In student collaboration in composition classrooms, we might wonder how we can engage students in collaborative work that avoids one student dominating the collaboration with input from their field of study, or that avoids students merely consulting the public in the collaboration as opposed to engaging and empowering them as equal contributors. We might also have to consider how to assign grades to collaborative authorship that ought to include non-students as collaborators and indeed as co-authors of submitted work.

In composition pedagogy theory, Bruce McComiskey has delineated a social-process model for composition; and more recently, composition scholars in the new materialism movement have considered the role of non-human authors in an always already collaborative composition process. Laura R. Micciche’s 2014 article Writing Material summarizes McComiskey’s correlation between collaborative writing and his social-process model, noting: “McComiskey's model, representative in its general approach of the pedagogical imprint made by the social turn, prioritizes superstructural forces—institutions, culture, politics—over minutia of producing and distributing writing” (492). For Micciche, this extension of authorship in composition beyond the author alone and toward not just additional authors, but also these “superstructural forces” allows for a much broader conception of collaboration in writing studies and composition pedagogy. Building on work in the digital humanities, Micciche works to redefine collaborative writing as a matter of “coexistence” (498). Micciche explains: “To think of writing as a practice of coexistence is to imagine a merging of various forms of matter—objects, pets, sounds, tools, books, bodies, spaces, feelings, and so on—in an activity not solely dependent on one's control but made possible by elements that codetermine writing's possibilities” (498). From the new materialist standpoint, then, writing has always been radically collaborative, including non-human participants. The social-process view of collaboration in composition studies has emerged as the predominant influence in recent scholarship, especially in studies of translingualism (Wang), and the role of conversation in developing disciplinary knowledge (Winzenried, et al.).

In transdisciplinary theory, Brown et al. proposes that these five knowledge cultures can operate in transdisciplinary research not through division, but by conducting “synoptic” and “synergistic” inquires in a “collective social learning spiral” asking: 1) What should be? (Reflecting Ideals); 2) What is? (Facts); 3) What could be? (Generating New Ideas); and 4) What can be? (Actions) (76-77). This sequence, described by the authors, enables distinct labor roles to operate collectively and equivalently, avoiding the common divisional approach. This collective social learning spiral can be a useful heuristic to incorporate in collaborative writing pedagogy centered on transdisciplinary questions.

When we synthesize the observations of this transdisciplinary research activity systems analysis, we gain an understanding of transdisciplinary inquiry that we can begin to utilize in theorizing a composition studies framework (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. A Transdisciplinary Activity System

Transdisciplinary Activity Systems and their Writing Challenges: A Composition Theory Framework for Transdisciplinary Research Collaboration

As the complex activity system of transdisciplinary research comes into view, we are left to consider the connective tissue between composition theory and transdisciplinary theory, especially composition pedagogy’s entanglement with disciplinary boundaries and boundedness to the campus or classroom, with privileging a rhetorical style of certainty and argumentative modes, and with the individualized author in student assessment.

Transdisciplinary research may require a shift in how composition and WAC/WID programs approach collaboration in the writing classroom. One challenge with collaborative writing pedagogy in transdisciplinary research settings is that teaching for transdisciplinary collaboration will require teaching students to avoid what Ede and Lunsford have described as the “hierarchical mode” of collaboration; composition instructors will instead need to emphasize a “dialogic” mode of collaboration where all participants have equal input. This may create tension in classrooms where teacher-student hierarchies are prominent and where students are encouraged to become leaders of a collaboration instead of radically equal participants.

A second challenge originates in what Gere et al. identify as the traditional disciplinary structures of departments and institutions. While transdisciplinary research collaborations don’t draw such boundaries around participants, our classrooms are often bounded-by-design—bound to enrolled students, bound to a physical space, bound to novice-expert relations, bound to grade policies and participation expectations, and bound by university policies that sometimes restrict student engagement beyond the classroom. A composition studies framework for transdisciplinary research will need to shift away from such bounded classrooms to allow for radically shifting collaborative teams.

A third challenge is that transdisciplinary research collaboration requires a movement away from deliberative theories that emphasize negotiation and concession as the basis of collaboration. Instead, transdisciplinary research collaborations aim for transformation of participant views such that a new view emerges among all participants by working through what Ede and Lunsford have called the “dialectical tension.” Thus, traditional models of collaboration that encourage a negotiated middle ground among collaborators will fall short of the transformational mission of transdisciplinary research.

Finally, engagement of all participants in what Lowry, Curtis, and Lowry delineate as pre-collaboration tasks (like group formation and problem defining) and post-collaboration tasks (like publication) presents challenges for collaborative writing pedagogies that pre-define projects and assignments for students, or pre-design the written projects or genres in which post-collaboration work is articulated. A collaborative writing project that controls the collaboration process by having instructors create the student groups and assign the collaborative writing genre for which points will ultimately be awarded falls far short of modeling transdisciplinary research collaboration. These problems are rooted in familiar traditions of composition pedagogy and make clear just how radically writing programs and institutions will need to change to prepare students for success as transdisciplinary collaborators.

These challenges outlined in recent works make clear that writing program curricula are often mapped onto complicated notions of disciplines and departments that are traditionally epistemological; but, as these boundaries and borderlands become more elastic, more collaborative, and more inter- and trans-disciplinary we must begin to consider how writing program curricula respond to the benefits of both disciplinarity and transdisciplinarity. This begs an important question for writing programs: How do we offer undergraduate students both the benefits of bounded disciplinary thinking and epistemological training while also teaching a communicative elasticity needed to transcend those boundaries as transdisciplinary collaborators? That is, transdisciplinary collaboration requires our students to both bring disciplinary rigor to the collaboration and be able to forsake it when necessary for the collaboration to succeed. One dilemma is that many composition programs emphasize first-year instruction, a time at which few students have yet to develop any or very minimal disciplinary or epistemological training. Elasticity can be taught as a threshold concept of sorts in these first-year courses through common approaches like genre and audience awareness; but, asking first-year students to engage in rigorous disciplinary genres or writing for disciplinary audiences in their first year would seem nonsensical if those students had yet to take any advanced courses in their disciplines.

Recent works in composition studies have theorized how WAC/WID programs might take better account of disciplinary elasticity in what Paul Prior has framed as “new disciplinarity” (in Gere, et al.) and address a shift in university curricula from disciplinarity toward transdisciplinarity (Rademaekers; Serviss and Voss). Gere et al. examine the historic WID program at the University of Michigan with attention to the ways that the writing program is overlaid onto departmentalized disciplines, shared university resources, disciplinary epistemologies, and goals or expectations for students. Gere et al. make the case that while boundaries exist among departments and disciplines, the disciplines also exhibit elasticity within those traditional boundaries and more closely resemble a new disciplinarity with “dynamic borderlands” than they do traditional, bounded, disciplines (247). The authors make clear that their own institution’s “upper-level writing requirement” (and WAC/WID pedagogy more broadly) is often problematically wedded to traditional notions of disciplinarity that presume participation in upper-division writing in the major is the means through which students ought to develop as academic and/or professional writers.

At the heart of the problem for composition and WAC/WID programs, then, is a deeper dilemma for twenty-first century institutions that composition studies must address: do we still wish to describe a “discipline as an ‘epistemological unit’” (Gere et al. 261) organized and owned by departments or does interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity ultimately mean that epistemology must be decoupled from disciplines and departments? In my 2015 Across the Disciplines article, I reviewed some of the “common communicative barriers” that emerge in transdisciplinary collaborations and suggest that the root of many of these communicative challenges is the notion of disciplinarity itself. In that work I argued for writing studies scholars to “consider approaches to writing to learn pedagogy which teach disciplinary discourse reflexively, revealing disciplinary conventions, but portraying them as situated, and negotiable in transdisciplinary collaborative settings” and to “consider ways to integrate writing to learn pedagogy with opportunities for transdisciplinary collaboration, including teaching the skills of negotiating difference among divergent disciplines and teaching written genres that act as tools for mediating such differences” (12). Serviss and Voss’s 2019 article Research Writing Program Administration Expertise proposes a model for cross-disciplinary writing program work based in transdisciplinary method. Serviss and Voss complicate my suggestion that disciplinarity necessarily troubles transdisciplinary collaboration noting that their team’s:

effectiveness was bolstered by each member’s different background, rather than limited to established shared knowledge or consensus” and that “Drawing on varied and even divergent expertise contributed to the group’s success. Focus on a situated, shared problem and the affordances of our aggregated expertise was much more significant to the team’s success than the transcending (that is, abandoning) of our disciplinarity [sic] identities to establish a small, consensus-driven collective identity. (452-3)

Thus, Serviss and Voss suggest that disciplinarity becomes a source of expertise that is essential to a group’s success, though transcending and abandoning some of this disciplinarity remains important. The role of disciplinary rigor and traditional departmentalized training in the radically interdisciplinary and collaborative modes of inquiry on the road ahead requires further scrutiny.

***

Let’s imagine that in the next decade more and more universities begin to direct their attention to transdisciplinary research—a trend which has already begun at places like Arizona State University, Australia National University, and the University of Pennsylvania. Undergraduate general education courses centered on applied problems like energy infrastructure might gather students from diverse disciplines to deliberate with one another. As indicated in Figure 2, such courses would necessarily also engage the broader community in their research processes and strive for total equivalence among knowledge cultures. We might imagine administrators feverishly beginning to check off the elements of their strategic plans that these collaborations enable: undergraduate research, interdisciplinary inquiry, community engagement, applied problem solving, and more. In such a case, writing programs, no doubt, would need to prepare faculty and students for the rhetoric and writing activities of such transdisciplinary courses; and as this article has tried to make clear, the task is no easy feat. Undergraduate students from diverse backgrounds and disciplines, almost all of whom are fledgling members of their own discourse communities, working in teams with peers to propose solutions to an applied problem through a process informed by community engagement—yikes! Such activities are as rhetorically complex as we can imagine.

So how should writing program directors act? What theories of rhetoric and writing apply to transdisciplinary research activities? Which composition theories and what tools do we highlight at our faculty workshops? An overview and activity systems analysis of transdisciplinary collaborations offers some cursory implications for composition program development and administration that universities looking to embrace transdisciplinary research and prepare students for success in transdisciplinary research collaboration ought to consider. These implications are certainly not limited to writing programs alone but are important to note because writing programs have historically played a central role in preparing undergraduate students to be effective communicators and collaborators.

From First-Year General Education Writing to Last-Year Collaborative Writing

Programs looking to prepare students for success in transdisciplinary research collaboration will have to find ways to resist what Gere et al. describe as the institutional “conflation of department and epistemology” (247) wherein firm departmentalization and resources confine students into disciplines that are presented as though a discipline owns objects of inquiry, epistemological methods, and controls the discourse communities where research on those objects are discussed. While Serviss and Voss make clear that disciplinary training can be a positive and productive source for participants in collaborations, a lack of elasticity in these disciplinary boundaries makes it difficult for students to collaborate on problems and objects that matter to every discipline. Moreover, undergraduate study is often designed to move from general education to disciplinary education with each successive year of study. For example, while many first year writing programs are designed as general education courses and in ways that appeal to students of all majors, these general courses that group students from many disciplines and majors become, unfortunately, increasingly less common in the upper division. Thus, the institutional resources for a third- or fourth-year course that would engage students in transdisciplinary research collaboration with students from all different disciplines become sparse because many universities view these years as reserved for disciplinary training rather than general education collaboration. Those precious final thirty or forty credits of undergraduate education are often the place where departments invest their greatest institutional resources and writing programs seeking to model transdisciplinary research collaboration with upper division students will be in direct contention with this traditional emphasis on disciplinarity in the upper-division. Development of upper-division general education courses that offer students from multiple disciplines opportunities to address an applied problem using transdisciplinary collaboration will be an important step for universities and programs to take, but such courses will also have to find a way to exist outside of a traditional university structure in which courses and faculty are defined by disciplines and departments.

Decentering the Instructor, the Individual, and the University

Programs that succeed in establishing an upper-division transdisciplinary research collaboration experience that coalesces students from many disciplines around an applied problem will have to help prepare faculty all across the curriculum for instruction in not just writing and communication pedagogy, but also: civic engagement and community-based participatory research; team-teaching and inter-faculty collaboration; and feminist pedagogies that de-center instruction and privilege dialogic collaboration over hierarchical collaboration. Ede and Lunsford argue that to utilize dialogic collaboration in place of hierarchical collaboration, participants must “resist or subvert the traditional culture of schooling” (136), which includes cultures of authorship, power, and authority in an abundantly white, masculine, European-dominated academic and research culture. In their follow-up publication, Lunsford and Ede encourage their readers to think of “dialogic collaboration” as requiring “rhetoric in a new key” as we move from hierarchical to dialogical modes. If successful transdisciplinary research collaborations emphasize dialogic collaboration and embrace ignorance and uncertainty, then this will most certainly contest traditional teacher-student relations across the curriculum and faculty will need help developing in their roles as collaborators (rather than instructors). Engaging students in transdisciplinary collaboration, for example, may mean moving away from approaches to composition that focus on argumentative defense of a position as effective writing. Such an approach may prove problematic in transdisciplinary contexts because: a) this approach centers written communication around the position and beliefs of the individual/student, rather than the collaborative voice and consensus of a wider group; and b) by emphasizing defense of a position this approach excludes ignorance and uncertainty, which are important values in transdisciplinary work. Instead, a composition pedagogy for transdisciplinary collaboration may mean moving toward students expressing their positions with argument or defense such that the positions can be considered dialogically as a basis for collaboration.

Troubling Authorship in Student Assessment

Programs preparing students for success in transdisciplinary research collaboration may also need to re-consider student authorship as the basis for grading and evaluation. One reason for this is because the deliverable or outcome of a transdisciplinary research collaboration is determined not a priori, but by participants. Thus, faculty collaborators in such a classroom would have no way of accounting for such a project in a course syllabus or assigning a point value to the project prior to the start of the course. Another dilemma here is that writing courses very commonly assign a written assignment as the product of a collaborative or independent process, but offering all participants in a transdisciplinary research collaboration total equivalence in the collaboration means engaging non-students in the production of texts which are traditionally associated with graded authorship. Thus, if any writing does emerge as a deliverable from the transdisciplinary research collaboration, it ought not to be solely the work of students, but should also have been composed by specialists, community representatives, individuals, organizations, and holistic thinkers. Rather than associating student authorship with grading and evaluations as writing courses often do, courses based in transdisciplinary research collaborations may need to emphasize evaluation of other outcomes such as consensus seeking, openness to transformation, maintenance of total equivalency in the collaboration, and respectful engagement with diverse viewpoints. For example, instead of assessing a collaborative publication, students might be asked to map the input of different collaborators (themselves, peers, organizations, specialists, selected readings, engaged citizens) and reflect on how the input of each of these collaborators contributed toward the dialogic consensus reached. Students might also reflect on barriers to the collaboration and where and why it may have failed. By assessing a map or written reflection such as this, faculty can emphasize the work of collaboration as the object of the course, rather than a final production or deliverable.

***

Universities across the globe have begun to invest heavily in transdisciplinary research, and this complex form of collaboration offers exciting new potential for addressing applied problems in a radically open and collaborative way. Writing programs seeking to prepare students for this kind of work, whether by self-initiation or administrative mandate, will need to consider which elements of composition pedagogy fit within the transdisciplinary framework and which do not. Not surprisingly, feminist rhetorics of science, theories of collaborative writing pedagogy, literature on community-based participatory research, and research in second language studies have already provided a great deal of information on open, situated, and dialogic meaning making. Now a great deal of work lies ahead in synthesizing and connecting such theories to writing programs and composition pedagogy for transdisciplinary research—a vital space in university curricula for preparing students to address questions of dire concern to twenty-first century communities. As successive generations are tasked with making sense of our most wicked problems, their success may well depend on their performance as transdisciplinary collaborators, and composition pedagogy will play a formative role in preparing us all for this challenge.

Works Cited

Bacon, Jen. Getting the Story Straight: Coming out Narratives and the Possibility of a Cultural Rhetoric. World Englishes, vol. 17 no. 2, 1998, pp. 249-258.

Bawarshi, Anis. Sites of Invention: Genre and the Enactment of First-Year Writing. Concepts in Composition: Theory and Practice in the Teaching of Writing, edited by I.L. Clarke, Routledge, 2012, pp. 208-226.

Brown, Valerie A., Peter M. Dean, John A. Harris, and Jacqueline Y. Russel Towards a Just and Sustainable Future. Tackling Wicked Problems through the Transdisciplinary Imagination, edited by Brown, Valerie A., Harris, John, and Russell, Jaqueline, Earthscan, 2010, pp. 3-15.

Brown, et al., editors. Tackling Wicked Problems through the Transdisciplinary Imagination, Earthcan, 2010.

Cintron, Ralph. Angels' Town: Chero Ways, Gang Life, and Rhetorics of the Everyday. Beacon Press, 1997.

Coogan, David. Service Learning and Social Change: The Case for Materialist Rhetoric. College Composition and Communication, vol. 57 no. 4, 2006, pp. 667-693.

Creswell, John W. Research design. Sage Publications. 2003.

Ede, Lisa S., and Andrea A. Lunsford Singular Texts/Plural Authors: Perspectives on Collaborative Writing. SIU Press, 1990.

Gere, Anne Ruggles, Sarah C. Swofford, Naomi Silver, and Melody Pugh. "Interrogating disciplines/disciplinarity in WAC/WID: An institutional study." College Composition and Communication, vol. 67, no. 2, 2015, pp. 243-266. Harris, Randy A. Introduction. Rhetoric and Incommensurability., edited by Randy A. Harris, Parlor Press, 2005, pp. 3-149.

Kasemvilas, Sumonta, and Lorne Olfman. Design Alternatives for a MediaWiki to Support Collaborative Writing. Journal of Information, Information Technology, and Organizations, vol. 4, 2009, pp. 87-106.

Kells, Michelle Hall. Writing Across Communities: Deliberation and the Discursive Possibilities of WAC. Reflections: A Journal of Writing, Service-Learning, and Community Literacy, vol. 6, no. 1, 2007, pp. 87-108.

Klein, Julie Thompson. Prospects for Transdisciplinarity. Futures, vol. 36, no. 4, 2004, pp. 515-526.

Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago UP, 1962.

LaFrance, Michelle and Melissa Nicolas. "Institutional Ethnography as Materialist Framework for Writing Program Research and the Faculty-Staff Work Standpoints Project." College Composition and Communication, vol. 64, no. 1, 2012, pp. 130-150.

Lave, Jean, and Etienne Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge UP, 1991.

Leavy, Patricia. Essentials of Transdisciplinary Research: Using Problem-Centered Methodologies. Routledge, 2016.

Lowry, Paul Benjamin, et al. "Building a Taxonomy and Nomenclature of Collaborative Writing to Improve Interdisciplinary Research and Practice." The Journal of Business Communication vol. 41, no. 1, 1991, pp. 66-99.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and Lisa Ede. Rhetoric in a New Key: Women and Collaboration. Rhetoric Review, vol. 8, no. 2, 1990, pp. 234-241.

Mays, Chris, and Maureen McBride. "Learning from Interdisciplinary Interactions: An Argument for Rhetorical Deliberation as a Framework for WID Faculty." Composition Forum, vol. 43, Spring 2020.

McComiskey, Bruce. Teaching Composition as a Social Process, Utah State UP, 2000.

Micciche, Laura R. "Writing Material." College English, vol. 76, no. 6, 2014, pp. 488-505.

Nowacek, Rebecca S. Why is Being Interdisciplinary so Very Hard to Do? Thoughts on the Perils and Promise of Interdisciplinary Pedagogy. College Composition and Communication, vol. 60, no. 3, 2009, pp. 493–516.

Parks, Steve, and Eli Goldblatt. Writing Beyond the Curriculum: Fostering New Collaborations in Literacy. College English, vol. 62, no. 5, 2000, pp. 584-606.

Powell, Malea. Rhetorics of Survivance: How American Indians use Writing. College Composition and Communication, vol. 53, no. 3, 2002, pp. 396-434.

Rademaekers, Justin K. Is WAC/WID Ready for the Transdisciplinary Research University? Across the Disciplines, vol. 12, no. 2, 2015.

Rodriguez Rojo, and Roxane Helena. Bakhtin Circle's Speech Genres Theory: Tools for a Transdisciplinary Analysis of Utterances in Didactic Practices. Genre in a Changing World, edited by Charles Bazerman, Adair Bonini and Debora Figueiredo., Parlor Press, 2009, pp. 295-316.

Russell, David R. Rethinking Genre in School and Society: An Activity Theory Analysis. Written Communication, vol. 14, no. 4, 1997, pp. 504-554.

Russell, Jacqueline Y. A Philosophical Framework for an Open and Critical Transdisciplinary Inquiry. Tackling Wicked Problems through the Transdisciplinary Imagination, edited by Valerie A. Brown, John Harris, and Jacqueline Russell, Earthscan, 2010, pp. 31-60.

Samraj, Betty, and John Swales. Writing in Conservation Biology: Searching for an Interdisciplinary Rhetoric. Language and Learning Across the Disciplines, vol. 3, no. 3, 2000, pp. 36-56.

Schaefer, Katherine L. ’Emphasizing Similarity’ but not ‘Eliding Difference’: Exploring sub-Disciplinary Differences as a Way to Teach Genre Flexibly. The WAC Journal, vol. 26, 2015, pp. 36-55.

Serviss, Tricia, and Julia Voss. "Researching Writing Program Administration Expertise in Action: A Case Study of Collaborative Problem Solving as Transdisciplinary Practice." College Composition and Communication, vol. 70, no. 3, 2019, pp. 446-475.

Shapiro, Michael J. Studies in Trans-disciplinary Method: After the Aesthetic Turn. Routledge, 2013.

Smithson, Michael. Ignorance and Uncertainty. Tackling Wicked Problems through the Transdisciplinary Imagination, edited by Valerie A. Brown, John Harris, and Jaqueline Russell, Earthscan, 2010, pp. 84-97.

Spinuzzi, Clay. Losing by Expanding: Corralling the Runaway Object. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 25, no. 4, 2011, pp. 449-486.

Swales, John. The Concept of Discourse Community. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings, Cambridge UP, 1990, pp. 21-32.

Wang, Zhaozhe. "Rethinking Translingual as a Transdisciplinary Rhetoric: Broadening the Dialogic Space." Composition Forum. Vol. 40. 2018.

Winzenried, Misty Anne, et al. "Co-Constructing Writing Knowledge: Students' Collaborative Talk across Contexts." Composition Forum, vol. 37, Fall 2017.

Zawacki, Terry M. and Ashley T. Williams. Is it Still WAC? Writing with Interdisciplinary Learning Communities. WAC for the New Millennium: Strategies for Continuing Writing-Across-the-Curriculum Programs, edited by Susan H. McLeod, et al., National Council of Teachers of English, 2001, pp. 109-140.

Transdisciplinary Collaboration from Composition Forum 51 (Spring 2023)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/51/transdisciplinary-collaboration.php

© Copyright 2023 Justin K. Rademaekers.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 51 table of contents.