Composition Forum 51, Spring 2023

http://compositionforum.com/issue/51/

Localizing Curricula through Collective Actions: A Case of Aspirational Change at a Newly Designated Hispanic Serving Institution

Abstract: This program profile focuses on the collective work and beginning stages of moving a very large writing program from default orientations of predominantly white institutions (PWI) to practices responsive to Hispanic-serving institution (HSI) opportunities over a five-year period. Throughout this profile, I narrate how faculty of all ranks within the first-year composition program at the University of Central Florida worked together to turn the belief that all students’ language and literacy practices are worth sustaining and expanding into an action-oriented sociocultural literacy model. For other programs interested in or needing to undergo similar redressing, this profile offers a story of change that culminates in outcomes development, and that includes examples of our community’s collective actions to localize curricula towards students’ languages, literacies, and rhetorics. Specific emphasis of each phase of work (from 2017-2022) might be useful as programs embark on large-scale change; or the spirit of each movement might be more useful.

This profile of the first-year composition (FYC) program at the University of Central Florida (UCF) offers an example of how one FYC program enacted curricular and cultural change over time with goals of developing a sociocultural, assets-based, and translingual orientation towards writing instruction. I am writing this profile from the position of program director (having since transitioned from that role in May 2022) and have tried my best to capture the trajectory of a program initiative to “develop and foster inclusive, asset-based teaching practices by localizing our writing about writing curriculum” (email correspondence from director to faculty, Aug. 2017) over a five-year period. From this perspective, I reflect on how faculty of all ranks within the FYC program at UCF worked collaboratively, systematically, and through a value system based in equity, access, and sustainability to transform writing instruction alongside our university’s transition to becoming a Hispanic-serving institution (HSI). Thus, the story in this profile is about our efforts and actions to transform writing and programming practices from default orientations of predominantly white institutions (PWI) to practices responsive to HSI needs between May 2017-May 2022.

This collective work, which involved commitment from faculty of all ranks (TT, NNT, adjuncts, and GTAs), further expanded students’ “opportunity to learn” (Poe, Inoue, and Elliot 4) in the one of the country’s largest FYC programs. As I chronicle, efforts were anchored in integrity of values, respect for faculty expertise and labor, scholarly research and local data, and the belief that all students’ language and literacy practices are worth sustaining. For other programs interested in or needing to undergo similar transitions, this profile offers a procedure for change that culminates in outcomes development, and that stems from localized needs and expertise while also drawing from the relevant research and theory within writing studies and allied fields. Specifically, it presents how our community worked toward a local, sociocultural literacy model developed explicitly with students at linguistically, racially, and socioeconomically diverse institutions like UCF in mind. Of course, five years is both a long and a short time frame. Thus, at UCF, we’ve only just begun to make headway in the direction of equity and fairness for all student writers. Moving forward, as new practices and policies develop, it is critical to foreground that, “because the HSI designation is not part of the founding or purpose of these institutions, but is rather connected to a student demographic percentage, the HSI designation is less actively utilized as part of the organizing identity than other institutional designations” (Gonzales et al. 71). This means that proactive, deliberate, and continuous efforts are required for substantive and lasting change that extend far beyond the timeframe chronicled here.

General Program Overview and Description

The First-Year Composition Program at UCF resides within a standalone Department of Writing and Rhetoric (DWR) and contributes to a vertical and wrap-around writing curriculum alongside a major and minor in Writing and Rhetoric, a M.A. in Rhetoric and Composition, the University Writing Center, and a Writing Across the Curriculum program. All are housed within DWR and the College of Arts and Humanities. The program serves between 6,000-8,000 students annually from the larger UCF population of approximately 60,000 undergraduates. Our first-year program consists of two courses, ENC 1101 and ENC 1102, which together support the university’s general education communications requirement.

UCF’s FYC program is staffed predominantly by fulltime instructors, both nontenure stream and tenure stream. Currently, a small number of graduate teaching assistants (10-12), adjunct faculty (6-8), and visiting instructors (3-4) also contribute to teaching ENC 1101/1102. This labor configuration dates to the founding of our standalone department in 2010 and is indebted to the work of then FYC director, Elizabeth Wardle, and future FYC directors and department heads. For readers interested in the program’s movement from a heavily adjunct-based to a primarily fulltime-based writing staff, please visit the excellent description of this process and outcome from a Spring 2013 Program Profile (Wardle){1}. Frustratingly, our program has not been able to remove all the hierarchies embedded in structures of rank, longevity, compensation, and labor stability, but we actively seek to create environments that can challenge them, building opportunities for all voices to shape our programmatic work. This is all with the understanding, of course, that discursive equity alone does not counter contingent labor systems built on economic and material inequities. Additionally, during my time as director, I must acknowledge the support of our team’s work through materials, resources, and professional expertise, which I advocated for upon assuming my role as director, knowing that any strategic vision without accompanying resources would remain largely dormant. During my time as WPA, our program was supported by a team of three administrators—the director and two composition coordinators (coordinators are full time faculty) all with course reassignments—with opportunities, as available, for graduate assistants interested in writing programs to work on curriculum design and teacher training.

In May 2017, UCF was in the beginning phase of applying for federal HSI status. It was clear that a key goal of our program had to be to address and redress exclusions related to students’ languages and literacies. In 2019, UCF was formally recognized by the US Department of Education as an HSI after it exceeded its 25% threshold of Hispanic/ Latina/o/x{2} undergraduate student population in 2017. UCF currently enrolls 19,585 (27.8% of student population) Hispanic/ Latina/o/x students and has grown 4% in this student population in the past three years. While Hispanic/ Latina/o/x student identity is not a direct correlation to Spanish language speakers, a 2018 survey of all FYC students revealed that 21% of students self-identified Spanish as their primary language. Beyond Hispanic/ Latina/o/x, UCF’s overall student population is from a range of racially and ethnically diverse communities. UCF also serves many first-generation students, with 18.7% of our total undergraduate population identifying as first generation. It is within this context that the program’s administrative team along with core groups of dedicated faculty worked toward intentional and research-based curricular design to localize our curriculum towards students’ sociocultural languages, literacies, and rhetorics. The remainder of this profile describes the key values and activities that drove that goal.

Justice-Oriented Transformations and Programmatic Actions from 2017-2022

The composition program transferred directorship in 2017 with a strong writing about writing foundation across two courses (ENC 1101 and ENC 1102) within a program and department culture that emphasized faculty’s disciplinary expertise in writing and was unequivocal about the value of first year writing. From this base, the composition program launched in Fall 2017 a programmatic initiative driven by three key orientations: curricular localization of writing about writing to attend to linguistic and literacy diversity at UCF, the integration of social justice into programmatic practices and policies, and a clearer response to the heterogenous/pluralistic realities of students’ past and future writing lives. The exigency for these shifts was multiple. First, UCF was in the process of applying for Hispanic-serving institution status. Second, UCF was already a racially and ethnically diverse institution and needed a composition program that could sustain the literacies and languages of historically excluded students. Third, in recognition of UCF’s racial and ethnic diversity (with and beyond Hispanic/ Latina/o/x students), it was imperative to center students’ linguistic diversity, and yet the curriculum at that time did not address language or sociolinguistics. Fourth, it was time to center the empirical realities of writing in heterogenous and globalized settings, where writers and audiences bring situated knowledges from a range of genres, languages, rhetorical traditions, literacy practices, and communal and individualized experiences in meaning-making. Finally, we recognized the need to readdress a more protracted exigency: educational and linguistic injustices promulgated through narrow and limited sets of declarative and procedural knowledges around writing, literacy, rhetoric, and language. This starting point of five exigencies set in motion a five-year period of research, planning, and activities that culminated in fully revised learning outcomes and an accompanying assessment plan and vision in May 2022. Specific emphasis of each phase might be useful for other programs who embark on large-scale change, or the spirit of each movement might be more useful.

Year 1: Defining Long-Term Goals and Exigency Setting through Empirical Research on Local Literacies/Languages, 2017-2018.{3} While the composition program team had identified exigencies as the base for programmatic change, it was imperative to invite all program faculty from every rank into this dialogue and data. I called year one “exigency setting,” which included a series of professional development seminar-style meetings (four total) that would launch actions for years two through five. In early Fall of 2017, I sent a memo via email to all department faculty that presented the following initiative:

To develop and foster inclusive, asset-based teaching practices by localizing our writing about writing curriculum. This initiative builds on our current curriculum by considering who our UCF students are, what resources and experiences they bring to the classroom, and how we might adjust our curriculum to ensure all students are receiving equitable literacy education. We ask the question: What is our program’s role in teaching writing with and for a fundamentally pluralistic society?

Over four subsequent gatherings, we invited faculty to see the need for “developing and fostering inclusive pedagogical practices by localizing our writing about writing curriculum” (from Comp Talk 1). Throughout these meetings, we presented and invited discussion around language and literacy data of our students and local, regional, and state community data. Data were collected through student surveys of FYC writers and extensive research from Census data, the Florida Department of Education, and data from local high schools and community colleges.

In addition to student language and literacy data, we also situated our work during this first year in scholarship on language diversity, writing across communities, and culturally sustaining pedagogies and sought to connect these with our writing about writing curriculum{4}. We introduced Christine Tardy’s excellent work on Enacting and Transforming Local Language Policies. Here, building on the work of Alistair Pennycook, Tardy argues for investigating three components that make up language policy, but within programs: “...language practices—the habitual pattern of selecting among the varieties that make up its linguistic repertoire; its language beliefs or ideology—the beliefs about language and language use; and any specific efforts to modify or influence that practice by any kind of language intervention, planning, or management” (639). Our longer-term aim was to transform our program’s de facto and de jure policies using the local language policy framework offered by Tardy. Having presented our arguments of need to program faculty in year one, we closed out that school year with the future goals of amending our implicit language framing and making concrete places to link initiative efforts to already existing practices, genres, and curricular infrastructure.

From the onset of this endeavor, it was critical that groups that might be commonly excluded from programmatic decision making were invited to participate fully and to the level of their desired interest from the very onset of this process. We strove for what Jonna Gilfus has called “collective leadership,” which advocates for ways that TT and NTT faculty can collaborate on a program’s pressing issues in ways that “replace traditional hierarchical attitudes toward research and teaching with structures that respect and support the broader contributions of all faculty (467).” In an email sent to all department members, I outlined the ways in which collective leadership could support our work. In an email sent on 2/9/2018, I described the “Goals of Comp Talk 3: Building Theories through Collective Leadership.” The email stated the following:

Please join us as we start to develop together a robust and responsive theoretical framework for localizing writing about writing. We invite colleagues to help us define and generate a working theoretical framework that can guide our move toward more localized and inclusive curriculum. Participants can anticipate faculty-driven discussion and definition-making that will, in turn, help guide the Program's next steps in professional and curricular development.

In Comp Talk 3, the development of a theoretical frame that can orient our teaching and thinking about local curriculum is guided by the notion of collective leadership. This stance works against the notion of imposing initiatives or curricular changes without substantive conversation and collaboration with faculty. Rather, we invite “collaborative use of [faculty's] differing forms of expertise, experience, and interest, rather than relying solely on the leadership of those in designated administrative roles in the academic hierarchy” (Gilfus 470).

While assets-based approaches are typically used to describe classroom teaching contexts involving students and teachers, the stance of collective leadership encouraged an assets-based approach amongst and across all ranks that taught within the FYC program. In this way, the perfect middle was to imagine the strengths of students mingling with the strengths of teachers for a sustainable educational experience for all.

Year 2: Developing Faculty Expertise on Language Diversity from Scholarship, 2018-2019. In year two, I reconstituted the Composition Curriculum Committee (composed of faculty and first year composition teachers at all ranks) to start the grounded work of acting on the exigencies set in year one. This year was marked by extensive reading and discussion of scholarship from sociolinguistics, writing studies, education, and second language writing for the purposes of envisioning our “local language policy framework” and more explicitly including issues of language into the curriculum. While we initially wanted to jump right into our frameworks and guiding documents, we all realized that more reading, unlearning, and deliberation was necessary. In that spirit, we revisited writing about writing scholarship from which the program had been built and placed that in direct dialogue with research on language diversity and assets-based approaches. We held workshops using Samantha Looker-Koenings’ scholarly work and textbook on Language Diversity in Academic Writing, which makes an argument for connecting writing about writing with Students Rights to their Own Language. Our Composition Curriculum Committee also developed language attitudes, ideologies, and practices surveys for teachers and students. Unfortunately, we never distributed these surveys due to my parental leave in Fall 2019 and then the onset of COVID-19 in Spring 2020. Although we were unable to distribute the survey, discussions of survey questions as based in scholarship supported shifts in classroom instruction and provided an even more robust grounding for the development of an in-house language policy (developed in Fall 2019). During this time, committee members wrote additional threshold concepts around language, revised assignment sequences to extend commonly used prompts and in-class activities, and developed lesson plans drawn from culturally and linguistically sustaining methods to be shared with all faculty.

Joy, collaboration, humor, but also some anxiety over new directions characterized our meetings as we developed, presented, and workshopped ideas. Members shared and talked through trepidations related to including dimensions of race and language, especially, into classroom discussions and assignments. In choosing our professional development readings, I had purposefully included several texts on standard language ideology and raciolinguistics{5}. For many, sociolinguistics was a newer area of study and had not previously been a central feature of our composition program nor a central area of expertise for most members, although several faculty did have expertise (and growing expertise) in language study and were able to guide and support discussion and learning. Recognizing this new learning situation, colleagues with direct educational training in these areas and I began to plan for additional entry points for faculty to access and process newer concepts and intellectual traditions as we set strategic plans for collective professional development the following year. For instance, in Fall 2019, with gratitude to colleague Joel Schneier for attaining pre-distribution copies of an indispensable documentary on the history of Black language in the United States from enslavement to the present, the FYC program was able to screen and hold a discussion of Talking Black in America. With this source and others, we sought to supplement the often-dense scholarly articles we had been reading with other excellent resources through focus on multimedia and multimodality. Our hope was by diversifying our educational resources, we could invite more audiences into our learning and unlearning without the pressures of always engaging with high academic registers. Thus, this year was marked by learning, deliberate and creative changes at the level of practice, and naming the types and affective contours of learning/unlearning still needed and yet to come.

Year 3: Piloting Curriculum and Writing Public Facing Genres, 2019-2020. This year was marked by two significant activities: the development, piloting, and data collection of a critical language awareness informed ENC 1102 course (our second semester research writing course), and the drafting of our in-house language policy. Immediately prior to our pilot course development, program faculty continued our self-education and collaborative momentum to develop a language diversity statement (informed by Tardy’s language framework suggestions introduced in year one) to guide and ground the program on ways to approach/address linguistic variation in writing courses. Known locally as our “language principle,” this work built from scholarship on translingualism, critical language awareness, and raciolinguistics, and started the phase of publicly documenting programmatic commitments to honor and sustain students’ linguistic resources and rhetorical practices. Readers will note the influence of Horner et al., for instance, in our affirmation that “language variation is the norm and not the exception in all situations and writing activities.” The language principle was developed iteratively through group discussion and is tied directly to field scholarship and to UCF students’ language and literacy experiences.

Writers need to understand that language variation is the norm and not the exception in all situations and writing activities. Thus, the goal for writers is not a singular standardization, but how to build upon their existing proficiencies to negotiate language in use in real rhetorical and material situations. As a result, in ENC 1011 and 1102, we teach linguistic meta-awareness as opposed to acontextual standardized and rigid approaches to language use, as an integral part of engaging in all ill-structured writing problems. It follows that ENC 1101 and 1102 understands variation as an outcome of all living and lived languages rather than as so-called “error.” Students may bring variation to their writing as (1) part of language learning; (2) resistance to dominant language use and racialized language hierarchies; (3) purposeful use of a range of languages and dialects; and/or (4) creative play with language.

As noted, our statement developed through guided and collaborative authorship. Over a series of three meetings, I brought progressively more refined drafts of our statement crafted from faculty input. For instance, in an early meeting, I presented our group with a set of questions for developing our statement alongside a set of salient quotations from prior readings that members had identified as resonating with our aspirational work. We also deepened our learning during this time to include raciolinguistics and translingualism more explicitly in our group’s collective knowledge{6}. During meetings, I would take extensive notes, asking for clarification when needed, and bringing us back to the questions and goals at hand when helpful. Between meetings, I would write a draft of the principle, which would then be thoroughly workshopped and revised with the committee. The result was our co-authored commitment to language diversity at UCF.

Additionally, in Fall 2019, two faculty members and I developed a pilot ENC 1102 that would extend the existing writing about writing curriculum through critical language awareness. Two sections of this pilot course were taught by Esther Milu in Spring 2020, and data (from our IRB approved study) was collected by Joel Schneier and Esther Milu. Readers will recognize Spring 2020 as the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was also the semester that I was on parental leave. Incredibly, Esther taught her courses amidst the transition to online teaching in Spring 2020, and Joel collected interview and survey data under these same circumstances. Since that time, we have reflected on, presented on, and written about the impacts of this course on student learning, especially as they connect to goals of undergraduate research in HSIs. As we write elsewhere, “From this [study], we suggest that centering student knowledge and experience in language themed UGR courses has the potential to redefine contributive research as an increasingly inclusive sociocultural literacy, especially for students whose languaging practices have been historically excluded from academic spaces. Such an approach emphasizes the continued rebalancing of undergraduate research away from alienation of topic, method, and audience and toward student-defined and student-generated research and research-informed contributions.” Findings from this pilot study helped inform revisions to student learning outcomes for ENC 1102 as well as provided assignment and reading resources for program faculty.

Year 4: Initial Development of Refreshed Learning Outcomes and Examining Language Ideologies, 2020-2021. In year four, the program and our curriculum committee transitioned to outcomes revisions for ENC 1101 and 1102 and held several workshops to prepare faculty for using ePortfolios{7} in their courses for a refreshed programmatic assessment. As with all proceeding work, outcomes development and implementation were embedded within a grassroots and collective ethos. Our group met often to discuss and deliberate on new outcomes as guided by commitments to localize our work. It was also important to show continuity of values and aims as part of efforts towards recognizing sustainability, longevity, and respect for prior labor. To do this collaborative work, we started with a conversation around values for each course that was guided by orientations established over the prior three years. In an email to faculty (sent on 10/29/2020), I reiterated these shared values as follows:

Students’ expertise, experiences, and literacy and language histories are assets and given parity with field-based scholars

Language diversity is an empirical fact and reality, but language discrimination is also a fact and norm, especially for minoritized and racialized students; we must teach toward linguistic and educational justice.

We have taught about how writing and rhetoric work in the world; we now add how language works in the world.

Localizing our writing about writing curriculum to reflect, honor, and sustain UCF students' languages and literacies.

We need to focus on transfer to ill-structured and real world-like writing situations; this means highly heterogeneous situations, audiences, exigences, writers, NOT monolithic or monolingual audiences and contexts. Writing and language situations that [sic] are embedded in language and literacy ideologies that often privilege and often white mainstream language (especially in academic settings).

Discussions were far-reaching, sophisticated, and enlivening as faculty sought to both imagine new goals as well as reconcile competing goals for teaching writing in ways that supported and promoted students’ language and literacy practices. At this time, interest and commitment to language justice became centralized as a department-wide concern, and the department’s April Baker-Bell reading group, workshop, and campus{8} visit positively shaped our on-going learning outcomes revisions.

Although this year’s newly and collectively drafted outcome language didn’t directly transfer to the refreshed outcomes that I presented to program faculty in Fall 2021, that collaborative revisioning had several critical impacts. First, our curriculum committee meetings were places to come to terms with long-held curricular assumptions and engage in meaningful dialogue about values and principles we brought to the first-year composition classroom. Second, they allowed us to practice materializing the extensive literature and our program-generated language principle into our own words, phrases, and sentences and move those notions from theoretical abstractions to concrete, assessable aims. Third, these discussions were hugely important in community and trust building and helped to further gather faculty around principles of socially just writing education. The work of those on-going conversations happened over zoom, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and were moments of comradery, rallying around a common purpose, a brief respite from the stress of teaching at that time, and spaces for vulnerability and learning for all involved. At the end of that year, we had a draft revision of our ENC 1102 outcomes, which we presented to and got feedback from the department at large. These relational components and the buoying of our collective spirit served as a core foundation for the following year’s (2021-2022) careful, deliberative, and guided outcomes development. I believe much success of our outcome’s development, described next, was indebted to the relationships and sense of trust forged in year four.

Year 5: Outcomes Development and Piloting within a Mission, Vision, and Values Framework, 2021-2022.{9} This year was full of action as we harvested what had been planted as a community way back in Fall 2017. Perhaps the most visible result from this year was our refreshed ENC 1101/1102 outcomes. Building from our work the prior year, and now with guidance from two outside consultants, Norbert Elliot and Mya Poe, in the Summer of 2021 I began the process of building a mission, vision, values, and outcomes framework to generate a local literacy model (as manifest in outcomes and assessment processes) supportive of UCF students’ writing lives. These statements, shown below, were derived from careful and deliberate study of (a) our writing program’s local literacy needs vis-a-vis diverse student writers and twenty-first century writing goals and related research (as gathered in year 1-2); (b) needs of UCF’s General Education Program and Gordon Rule requirements{10}; and (c) current work from writing studies, literacy studies, and sociolinguistics on the most effective and socially just approaches to teaching and assessing diverse student writers{11}. I presented mission, vision, values and revised outcomes (a much rougher and clunkier iteration of outcomes than what was communally revised throughout the year) at our department’s Fall 2021 start-of-the-year orientation.

Mission

First-Year Composition tailors Florida’s General Education Program and Gordon Rule requirements for ENC 1101 and ENC 1102 toward ethically minded writing instruction with the explicit intent of supporting student writing at and beyond UCF, a richly diverse and Hispanic Serving Institution.

The composition program is committed to supporting writing growth for diverse writers from a range of language and literacy traditions while also teaching transfer towards written participation in pluralistic societies. In highly heterogeneous societies like the U.S., writers need to understand that variation is the norm and not the exception for languages, literacies, and genres. Thus, the goal for writers is not an idealized standardization. Rather the composition program supports students’ building up their existing repertoires while also negotiating the complexities of changing rhetorical and material situations. As a result, in ENC 1011 and 1102, we teach sociocultural traditions and practices as opposed to rigid, prescriptivist, and a-contextual approaches to composing.

Vision

The First-Year Writing Program will examine its policies, systems, and practices to identify and address what is prohibitive and exclusionary for BIPOC, Latinx, and first-generation student populations. We aim to (a) reduce the equity gaps in ENC 1101 and 1102 and (b) revise our curriculum to reflect a literacy model supportive of culturally and linguistically diverse students. Assessment follows two trajectories to support advancement of opportunity for students in the First Year Composition Program:

Develop and revise as necessary a locally responsive literacy model to support multilingual writers, specifically Latinx (HSI) and other linguistically and culturally diverse students.

Emphasize an anti-racist analysis: equity gaps (i.e.: racialized outcomes in student success) indicate structural problems that must be identified and changed.

Values

Sociocultural approaches to writing and writing instruction.

Multilingual, translingual, and critical language awareness perspectives.

Assets-based literacy learning to support and sustain culturally and linguistically diverse writers.

Writing, rhetoric, and language as course content and activity as drawn from writing studies.

Transfer of writing and language related knowledge and practice across contexts and genres.

Democratization and accessibility of undergraduate research for all writers.

Public sharing and circulation of student writing.

Faculty expertise and ongoing professional development in writing pedagogy, research, and theory.

Collaboration, participation, and contributive knowledge-making by students and faculty.

While these statements above never reached a public audience beyond those who worked on outcomes development, they were internal guides to support the drafting process and served as anchors and measures of whether we were meeting our aims and commitments. For instance, one example of how we used the values statement for outcomes revision was through collaborative alignment activities. The following table below is taken from a curriculum committee meeting activity in Fall 2021 where the goal was to talk about whether an outcome connected with values and context. This is one of many collective practices where composition program faculty refined new outcomes. For this activity below, I brought the grid to a committee meeting and faculty spent time in small break out groups discussing whether the outcome was reflective of and honored the aims and principles within the stated values and research and location-based rationale columns. Faculty provided extensive feedback for further alignment from which I refined each outcome as needed. In addition to this being a useful process for outcomes revision, it was also an opportunity for our community to practice talking about our work through the mission, vision, values, and outcomes framework.

Table 1. Example Alignment Grid for Outcomes Development in ENC 1101 used in the Composition Curriculum Committee in Fall 2021

Outcomes |

Values |

Targeted Course |

Research and Location-based Rationale |

Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Students will be able to integrate and marshal multiple literacies within and across varied writing contexts to support their goals. |

Assets-based and translingual approach to literacy and language for lifespan learning Empowerment of student agency through negotiating differences across varied contexts, genres, languages, and modalities Negotiating differences in and across varied contexts, genres, languages, and modalities |

ENC 1101 |

From a sociocultural literacy model, writing is part of/supported by a broader set of practices including reading, speaking, listening, meshing, blending, translation, multimodality, and use of digital tools. To support diverse learners, we need to help students leverage practices that enhance and support writing development. It’s critical to also recognize these practices as rhetorical and thus changing across contexts and purpose. We support students when we (a) teach strategic use of multiple literacies in writing development and (b) honor and help sustain students’ own multiple literacy practices. |

ePortfolio Surveys Focus Groups |

Students will be able to identify, analyze, and critique variation in rhetorical and linguistic patterns, including their own, from a range of cultural, community, technological, workplace, and academic contexts. |

Assets-based and translingual approach to literacy and language for lifespan learning Critical language awareness Writing, rhetoric, and language are course content and activity Negotiating differences in and across varied contexts, genres, languages, and modalities |

ENC 1101 |

A sociocultural model recognizes the viability and effectiveness of all forms of community writing--one is not more superior than another and each has meaningful rhetorical and linguistic patterns, although some forms and genres have been elevated within logics of standard language ideology and white language hegemony. Students’ writing lives across multiple communities, cultures, and institutions. It’s important to elevate variation and difference across sociocultural/sociolinguistic traditions as the norm. To navigate variation, students need tools to identify patterns for analysis, critique, and production in ways that foreground their own goals and identities. Transfer for lifespan learning. |

ePortfolio Surveys Focus Groups |

Processes like the one just described took place alongside ongoing conversation and reflection with stakeholders for these new outcomes (namely program faculty and FYC students). Other activities with faculty included focus groups, writing annotations for each outcome, and ongoing feedback from those who were piloting new outcomes. A critical phase in this process was working directly with students in courses where outcomes were being piloted. A program coordinator, Megan Lambert, and I visited classes and held focus group interviews as well as sent out surveys to ENC 1101 and 1102 students to learn about their experiences working with these goals. The feedback from students was integral to our revision process. For instance, we learned what words and concepts were accessible or not and we learned what aims were and were not seen as valuable by students and why. In fact, our choice to provide “tags” to the beginning of each outcome was based on a student suggestion for more accessible language and for clarity on the most core teaching and assessing aim of each outcome. These “tags” are the bolded phrases that precede each outcome statement (see below).

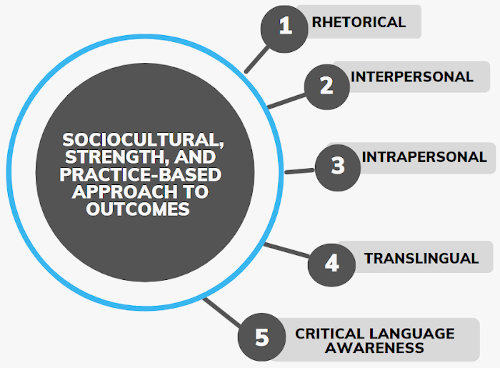

While working within a mission, vision, and values framework, we also developed and revised outcomes through variations on construct modeling (White, Elliot, and Peckman). Inspired by domain mapping models shared by Norbert Elliot on his work at South Florida University, we mapped a sociocultural and practice-based framework for a local literacy model that supported rhetorical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and practice and assets-based orientations (e.g. translingual and critical language awareness) to writing and writing development. These domains were also embedded within our values, but parsing them, as seen in the diagram below, further crystalized how each outcome could assist students in moving toward specifically meaningful writing capacities.

Figure 1. Domains that comprise our student learning outcomes across ENC 1101 and ENC 1102.

Through this constellation of sources and forces, a group of 15 tenure and nontenure faculty, adjuncts, and graduate students engaged in grassroots revision of student learning outcomes for ENC 1101 and ENC 1102 over an intensive one-year period. While outcomes revisions were on-going, additional and supportive professional development toward FYC program goals was happening through our excellent and long-standing DWR Reading Group, which lead discussions on Creole Composition: Academic Writing and Rhetoric in the Anglophone Caribbean as further insight into how to recognize and meet UCF student needs. Through activities such as these, we generated the following:

ENC 1101: Sociocultural Construct for Community Situated Writing

Writing Processes & Adaptation. Students will be able to describe and reflect on writing processes to flexibly adapt them to support their goals. [intrapersonal]

Multiple Literacies & Goal Setting. Students will be able to demonstrate how they marshal/leverage their multiple literacies (e.g., speaking, listening, reading, multilingual writing, translating, multimodality, etc.) to support their writing processes. [intrapersonal & translingual]

Variation across Contexts. Students will be able to identify, analyze, and reflect on variation in rhetorical and linguistic patterns, including their own, from a range of contexts (e.g., cultural, digital, workplace, and/or academic). [rhetorical & translingual]

Decision Making & Production. Students will be able to produce writing that demonstrates their ability to navigate choices and constraints when writing for specific audiences, genres, and purposes. [rhetorical & translingual]

Writing & Power. Students will be able to critically examine and act on the relationship among identity, literacy, language, and power. [critical language awareness]

Revision. Students will be able negotiate differences in and act with intention on feedback from readers when drafting, revising, and editing their writing. [interpersonal & translingual]

ENC 1102: Sociocultural Construct for Research Writing

Generating Inquiry. Students will be able to generate and explore genuine lines of inquiry related to writing, language, literacy, and/or rhetoric. [intrapersonal & rhetorical]

Multiple ways of writing. Students will be able to purposefully integrate multimodality, multiple languages, and/or multiliteracies into writing products to support their goals. [rhetorical & translingual]

Information Literacy. Students will be able to evaluate and act on criteria for relevance, credibility, and ethics when gathering, analyzing, and presenting primary and secondary source materials. [rhetorical & critical language awareness]

Research Genre Production. Students will be able to produce writing that demonstrates their ability to navigate choices and constraints in a variety of public and/or academic research genres that matter to specific communities. [rhetorical & critical language awareness]

Contributing Knowledge. Students will be able to draw conclusions based on analysis and interpretation of primary evidence and place that work in conversation with other source materials. [interpersonal & rhetorical]

Revision. Students will be able to negotiate differences in and act with intention on feedback from readers when drafting, revising, and editing their writing. [interpersonal & translingual]

The goal for developing outcomes in this way was to provide students with locally responsive sets of writing constructs to meet their existing strengths and evolving needs. Such an approach positions assessment within a holistic framework so that a program presents and works from a comprehensive view of writing and writing development that elevates the knowledge of both faculty and students. Critically, outcomes were faculty and student developed. It’s my hope that both audiences can see their aspirations and values for writing within these public outcomes documents.

Director’s Reflections and Lessons Learned

As of this profile’s writing, new course outcomes appear on the website of the University of Central Florida’s First Year Composition Program. But as with any solitary document, they can’t tell the story of the people, processes, and persistence that created those words and sentences. To give life and history to those pages, this profile provides a behind the scenes glimpse of one strand of writing program work at UCF: the five-year movement through an initiative to embed student learning and writing within local literacies and educational justice. As a tale of process and often invisible labor (with far more details and perspectives likely left out than included), this story is also a thank you note to everyone who has worked with the First Year Composition Program at the University of Central Florida during the five-year span described in this narrative (2017-2022) and earlier. I focused here on the collective work of moving a very large writing program toward programmatic change in ways responsive to students’ local writing realities in Orlando, Florida. Moving through the stages of visioning, collaborating, and laboring together, faculty with extraordinary expertise and commitment to the teaching of writing helped steer these cultural and programmatic transformations. The route to programmatic change outlined, while guided by strategic goals, phased plans, and articulated commitments set in motion in 2017, was also propelled by what Composition Coordinator Megan Lambert called our program teams’ and program faculty’s attunement to “magic.” Magic allowed us to follow our goals and yet make new meaning from new situations, needs, and constraints; form new aspirations in response to our available resources and institutional and societal changes; and with bravery when needed discard unfulfilled or unnecessary actions through the belief that we were conjuring change in the right direction and for the right reasons.

On the one hand, this profile offers some concrete actions to address curricular localization through collective efforts, the integration of social justice into programmatic practices and policies, and the deepening the recognition of the heterogenous/pluralistic realities of students’ past and future writing scenes. These include setting and expressing an exigency, learning and unlearning from scholarship and local literacies, developing and piloting courses, frameworks, and outcomes, setting and holding to aspirational goals, and inviting all community members to connect with those goals. On the other, I hope readers envision these actions as manifested within a community pulled by a willingness to reset and rethink actions while navigating types of institutional, societal, and cultural changes that impact workplace contexts, and especially those impacts from COVID-19. The official narrative here is that having a singular (but appropriately flexible) purpose to come back to again and again helps get things done. Cultural and programmatic change is on-going relational work that involves a constellation of actors and resources that change overtime. Collective and grassroots work takes a lot of time and effort and can grow deeper roots when everyone is invited in on their terms (or at least as much as possible). Creating new models, frames, and infrastructure is harder than dismantling or dismissing them. The unofficial narrative is that community work of this type means that colleagues become friends and mentors. Bonds grow when groups try out the unknown together. Sustainability is made in and through work, relations, and practice overtime. Change is one-part goal setting, two parts scaffolded planning, and three parts collective action{12}.

Appendix: Works Referenced for Theoretical and Research Basis of Mission, Values, and Outcomes

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth Wardle. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Alim, H. Samy, and Django Paris, editors. Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World. Teachers College Press, 2017.

Baker-Bell, April. Linguistic justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy. Routledge, 2020.

Barajas, Elias Domínguez. Crafting a Composition Pedagogy with Latino Students in Mind. Composition Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, 2017, pp. 216-218.

Brown, Tessa. What Else Do We Know? Translingualism and the History of SRTOL as Threshold Concepts in Our Field. College Composition and Communication, vol. 71, no. 4, 2020, pp. 591-619.

Bucholtz, Mary, and Kira Hall. All of the Above: New Coalitions in Sociocultural Linguistics. Journal of Sociolinguistics, vol. 12, no. 4, 2008, pp. 401-431.

Canagarajah, A. Suresh. The Place of World Englishes in Composition: Pluralization Continued. College Composition and Communication, vol. 57, no. 4, 2006, pp. 586-619.

Canagarajah, A. Suresh. Negotiating Translingual Literacy: An Enactment. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 48, no. 1, 2013, pp. 40-67.

Cullinan, Danica, and Neal Hutcheson. Talking Black in America. The Language and Life Project at NC State University, 2018.

Conference on College Composition and Communication. Students' Right to Their Own Language. Spec. Issue of College Composition and Communication, vol. 25, no. 3, 1974, pp. 1-3.

Davila, Bethany. Indexicality and Standard Edited American English: Examining the Link Between Conceptions of Standardness and Perceived Authorial Identity. Written Communication, vol. 29, no. 2, 2012, pp. 180-207.

Downs, Doug, and Elizabeth Wardle. Teaching about Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisioning ‘First-Year Composition’ as ‘Introduction to Writing Studies.’ College Composition and Communication, vol. 58, no. 4, 2007, pp. 552-584.

Elbow, Peter. Speaking as a Process: What Can It Offer Writing? Vernacular Eloquence: What Speech Can Bring to Writing. Oxford UP, 2011, pp. 59-77.

Elliot, Norbert. A Theory of Ethics for Writing Assessment. Journal of Writing Assessment, vol. 9, no. 1, 2016, pp. 2-16.

Flores, Nelson, and Jonathan Rosa. Undoing Appropriateness: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and Language Diversity in Education. Harvard Educational Review, vol. 85, no. 2, 2015, pp. 149-171.

Gere, Anne Ruggles, et al. Communal Justicing: Writing Assessment, Disciplinary Infrastructure, and the Case for Critical Language Awareness. College Composition and Communication, vol. 72, no. 3, February 2021.

Gonzales, Laura. Multimodality, Translingualism, and Rhetorical Genre Studies. Composition Forum, vol. 31, Spring 2015.

Guerra, Juan. Putting Literacy in its Place: Nomadic Consciousness and the Practice of Transcultural Repositioning. Rebellious Reading: The Dynamics of Chicana/o Cultural Literacy, edited by C. Gutiérrez-Jones, Santa Barbara: Center for Chicano Studies, 2004, pp. 19-37.

Grobman, Laurie. The Student Scholar: (Re) Negotiating Authorship and Authority. College Composition and Communication, vol. 61, no. 1, 2009, pp., W175-W196.

Horner, Bruce, et al. Toward a Multilingual Composition Scholarship: From English Only to a Translingual Norm. College Composition and Communication, vol. 63, no. 2, 2011, pp. 269-300.

Kareem, Jamila. A Critical Race Analysis of Transition-Level Writing Curriculum to Support the Racially Diverse Two-Year College. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 46, no. 4, 2019, pp. 271-296.

Kells, Michelle Hall. Linguistic Contact Zones in the College Writing Classroom: An Examination of Ethnolinguistic Identity and Language Attitudes. Written Communication, vol. 19, no. 1, 2002, pp. 5-43.

Kells, Michelle Hall. Writing Across Communities: Deliberation and the Discursive Possibilities of WAC. Reflections, vol. 6, no. 1, 2007, pp. 87-108.

Looker, Samantha. Writing About Language: Studying Language Diversity with First-Year Writers. Teaching English in the Two-Year College, vol. 44, no. 2, 2016, p. 176-198.

Martinez, Aja Y. A Plea for Critical Race Theory Counterstory: Stock Story Versus Counterstory Dialogues Concerning Alejandra's ‘Fit’ in the Academy. Composition Studies, vol. 42, no. 2, Fall 2014.

Matsuda, Paul. The Myth of Linguistic Homogeneity in U.S. College Composition. College English, vol. 68, no. 6, 2006, pp. 637-651.

Mihut, Ligia. Linguistic pluralism: A statement and a call to advocacy. Reflections, vol. 18, no. 2, 2018, pp. 66-86.

Milson-Whyte, Vivette, and Raymond Oenbring, editors. Creole Composition: Academic Writing and Rhetoric in the Anglophone Caribbean. Parlor Press LLC, 2019.

Milu, Esther. Diversity of Raciolinguistic Experiences in the Writing Classroom: An Argument for a Transnational Black Language Pedagogy. College English, vol. 83, no. 6, 2021, pp. 415-441.

Perry, Kristen H. What Is Literacy—A Critical Overview of Sociocultural Perspectives. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, vol. 8, no. 1, 2012.

Perryman-Clark, Staci M. Africanized Patterns of Expression: A Case Study of African American Students' Expository Writing Patterns Across Written Contexts. Pedagogy, vol. 12, no. 2, 2012, pp. 253-280.

Perryman-Clark, Staci M. Toward a Pedagogy of Linguistic Diversity: Understanding African American Linguistic Practices and Programmatic Learning Goals. Teaching English in the Two Year College, vol. 39, no. 3, 2012, pp. 230-246.

Pratt, Mary Louise. Arts of the Contact Zone. Profession, 1991, pp. 33-40.

Rosa, Jonathan, and Nelson Flores. Unsettling Race and Language: Toward a Raciolinguistic Perspective. Language in Society, vol. 46, no. 5, 2017, pp. 621-647.

Smitherman, Geneva Raciolinguistics, ‘Mis-Education,’ and Language Arts Teaching in the 21st Century. Language Arts Journal of Michigan, vol. 32, no. 2, Article 3. 2017, pp. 4-14.

Torrez, Estrella J. Translating Chicana Testimonios into Pedagogy for a White Midwestern Classroom. Chicana/Latina Studies, vol. 14, no. 2, 2015, pp. 101-130.

Wei, Li. Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language. Applied Linguistics, vol. 39, no. 1, 2018, pp. 9-30.

Williams-Farrier, Bonnie J. ‘Talkin’ bout Good & Bad’ Pedagogies: Code-Switching vs. Comparative Rhetorical Approaches. College Composition and Communication, vol. 69, no. 2, 2017, pp. 230-259.

Notes

More on this program’s history and emergence has been described by Wardle in a 2013 Composition Forum Program Profile, “Intractable Writing Programs.” I recommend reading that article to understand the unique historical context that precedes this profile. (Return to text.)

When deciding between Hispanic, Latina, Latino, Latinx, and Latine, I opted to use both Hispanic (prior studies show this a common identification used by UCF students themselves) and Latina/o/x (as suggested in Vidal-Ortiz and Martínez) to acknowledge multiple identifications. I would also like to acknowledge the ultimately impossible task of choosing such terms as representative and fully capturing the complexities of identity, race, ethnicity, gender identification, and geolinguistic and national location. (Return to text.)

The extensive research work done during this year was indebted especially to Dr. Jamila Kareem (FYC assistant director), Corrine Jones (graduate research assistant), Lissa Pompos Mansfield (FYC Composition Coordinator), and Nichole Stack (FYC Composition Coordinator). (Return to text.)

Please see the Appendix for the selection of works that informed this collective learning process. The Appendix includes readings from throughout this five year curricular transformation. Readings that informed our initial framing included Alim and Paris, Canagarajah, Downs and Wardle, Guerra, Kells, Matsuda, Perryman-Clark, Students’ Rights to Their Own Language, Tardy. Readings were used by the program team to shape vision and frame parts of each Comp Talk. (Return to text.)

Please see the Appendix for the selection of works that informed this collective learning process. Curriculum Committee readings from year two included Adler-Kassner and Wardle, Alim and Paris, Bucholtz and Hall, Students’ Rights to Their Own Language, Davila, Downs and Wardle, Gonzales, Guerra, Kells, Looker, Matsuda, Mihut, Perryman-Clark, Pratt, and Rosa and Flores. (Return to text.)

Again, please see the Appendix for the selection of works that informed this collective learning process. In addition to drawing on readings from year one, Year 3: Piloting Curriculum and Writing Public Facing Genres, 2019-2020 included learning from Cullinan and Hutcheson, Flores and Rosa, Horner et al., and Rosa and Flores. (Return to text.)

A special thank you is owed to composition coordinator Megan Lambert for her leadership on our program’s ePortfolio initiatives, professional development, and implementation. (Return to text.)

The principle reading during this phase was April Baker Bell’s Linguistic justice: Black Language, Literacy, Identity, and Pedagogy, which was part of a department-wide reading group and was coupled with a department-supported zoom workshop and talk by April Baker Bell. (Return to text.)

Additional discussion on the collaborative development of outcomes and the aspirations and values of ENC 1102 and ENC 1102 at UCF can be heard on the Department of Writing and Rhetoric's podcast, Episode 3, hosted by Meeghan Faulconer and Nikolas Gardiakos https://ucfdwr.podbean.com/e/episode-3-dr-angela-rounsaville-associate-professor-director-of-first-year-composition/. (Return to text.)

Within Florida, ENC 1101 and 1102 are two of the 9 required “communication foundation” credits (three courses) that make up the General Education Program (GEP); 6 of those credits (two courses) must be writing courses. ENC 1101 is considered a Florida state “black diamond course,” meaning it’s required for all students enrolled at the college level (i.e., all colleges and universities teach an ENC 1101). ENC 1102 is a prerequisite for all majors at UCF, although other Florida state colleges may have designated a different ENC course to fulfill the GEP requirement. A grade of C- or better is needed to meet this GEP requirement. ENC 1101 and 1102 are also so-called Gordon Rule (writing intensive) courses and fulfill half of the writing courses needed for that state requirement. (Return to text.)

In year five, given the goal of creating a robust sociocultural literacy model to support UCF students, I gathered another grouping of readings that would inform the mission, vision, values, and outcomes framework. Some of these readings were read and discussed by the curriculum committee and some were only read by me as I developed this framework. The majority of these were annotated by two graduate research assistants and made available for all program faculty as learning resources. In addition to earlier readings and resources, Year 5: Outcomes Development and Piloting within a Mission, Vision, and Values Framework, 2021-2022, was informed by Barajas, Brown, Canagarajah, Elbow, Elliot, Gere et al., Martinez, Grobman, Kareem, Milson-Whyte and Oenbring, Milu, Perry, Perryman-Clark, Smitherman, Torrez, Wei, Li, and Williams-Farrier. (Return to text.)

Thank you to the CCCC Writing Program Certificate of Excellence selection committee for awarding UCF’s First Year Composition Program with the 2022–2023 Certificate of Excellence for the work described in this profile, and more. The selection committee said that “The University of Central Florida First-Year Composition Program is an impressive representation of a writing program that is dedicated to authentic improvement based on student needs. Over the past few years, UCF has assessed and improved its programmatic goals and practices based on its diverse student population. After earning its Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) status, UCF endeavored to be explicit about valuing the linguistic and racial diversity of its students while still valuing the former transfer-focused writing goals. Achieving this goal included identifying and revising curriculum and training to support BIPOC, Latinx, and first-generation students. Additional successes emerging out of the UCF first-year composition program include its undergraduate journal, its early alert system for early student intervention, and its robust instructor professional development” (https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/awards/writingprogramcert). (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Cullinan, Danica, and Neal Hutcheson. Talking Black in America. The Language and Life Project at NC State University, 2018.

Gilfus, Jonna I. The Spaces In-Between: Independent Writing Programs as Sites of Collective Leadership. College English, vol. 79, no. 5, 2017, pp. 466-481.

Gonzales, Laura, et al. Testimonios from Faculty Developing Technical and Professional Writing Programs at Hispanic-Serving Institutions. Programmatic Perspectives, vol. 11, no. 2, 2020, pp. 67-92.

Horner, Bruce, et al. Toward a Multilingual Composition Scholarship: From English Only to a Translingual Norm. College Composition and Communication, vol. 63, no. 2, 2011, pp. 269-300.

Looker-Koenigs, Samantha. Language Diversity and Academic Writing: A Bedford Spotlight Reader. Bedford/Saint Martin’s, 2017.

Milson-Whyte, Vivette, and Raymond Oenbring, editors. Creole Composition: Academic Writing and Rhetoric in the Anglophone Caribbean. Parlor Press LLC, 2019.

Poe, Mya, Asao B. Inoue, and Norbert Elliot, editors. Writing Assessment, Social justice, and the Advancement of Opportunity. WAC Clearinghouse, 2018.

Rounsaville, Angela, et al. Contributive Knowledge Making and Critical Language Awareness: A Justice-Oriented Paradigm for Undergraduate Research at a Hispanic Serving Institution. College English Special Issue on Undergraduate Research, vol. 84, no. 6, 2022, pp. 519-545.

Rounsaville, Angela. Contributor. Dr. Angela Rounsaville: Director of First Year Composition. DWR Discussions on Writing and Rhetoric. February 2022. https://ucfdwr.podbean.com/e/episode-

Tardy, Christine M. Enacting and Transforming Local Language Policies. College Composition and Communication, vol. 62, no. 4, 2011, pp. 634-661.

UCF Facts 2021-2022: University of Central Florida--Orlando, FL. University of Central Florida, https://www.ucf.edu/about-ucf/facts/.

Vidal-Ortiz, Salvador, and Juliana Martínez. Latinx thoughts: Latinidad with an X. Latino Studies, Vol.16, no. 3, 2018, pp.384-395.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Intractable Writing Program Problems, Kairos, and Writing about Writing: A Profile of the University of Central Florida's First-Year Composition Program. Composition Forum. vol. 27, 2013. http://compositionforum.com/issue/27/ucf.php.

White, Edward M., Norbert Elliot, and Irvin Peckham. Very Like a Whale: The Assessment of Writing Programs. University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Localizing Curricula through Collective Actions from Composition Forum 51 (Spring 2023)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/51/ucf.php

© Copyright 2023 Angela R. Rounsaville.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 51 table of contents.